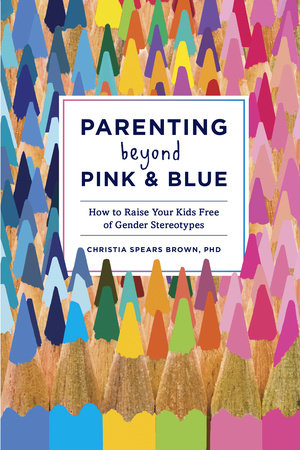

On Being the Weird Daughter-in-Law:

I am the weird daughter-in-law. I know it and have learned to embrace it. I first realized it when I overheard my sister-in-law whisper to my niece, “Let’s put that away. Aunt Christy won’t like it.” She was right. It was one of those light-up mirrors that girls use when they pretend to put on makeup. This pink plastic mirror came with plastic makeup and hair care products—and a voice. My skin crawled when it said, “You sure look pretty with that makeup on” or “Wow, your hair looks great!”

I quickly told my niece, who loves this makeup mirror, that I think she looks pretty all the time and that she is smart, funny, and interesting, which is even more important. Although I have no memory of it, my sister-in-law swears I took the batteries out of the mirror so that it couldn’t talk anymore. I am not saying I didn’t do it, and that is kind of my M.O.—the subversive editing out of gender stereotypes.

I used to do this often, quietly undoing as many gender stereotypes as I could in my children’s lives. After a while, I wasn’t so quiet. In my house, there is an explicit ban on pants with words written on the butt (I am not sure why someone thought it was a good idea for people to stare at the butt of a seven-year-old). My family knows about my hatred of Barbie (although she still sometimes sneaks in during Christmas). I often pull my older daughter, Maya, aside and say, “Just because Grandma thinks boys are stronger than girls doesn’t mean it is true.”

When Maya got the latest Barbie doll for her birthday, I remembered the experiment that found that girls who were given a Barbie to play with had a more negative view of their body and weight than girls who were given a more realistic doll. When she got the latest Disney princess movie, I mentally replayed the documentary

Mickey Mouse Monopoly. In it, a ten-year-old girl innocently states, in response to what she learned by watching

Beauty and the Beast, that she should just be nice to her boyfriend, even when he is mean to her (statistics about teen dating violence flashed through my head). So several birthday presents get “lost” in the trashcan between the party and the house.

Part of my problem is that I don’t want to be the weird mom or daughter-in-law, nor do I want my daughters to be “the weird kids.” I don’t want to put “No Barbies” on their birthday party invitations. I know some people will give Maya Barbies, but I also know that Maya will get other toys she’ll enjoy too, and that she’s never once missed or asked about a disappearing Barbie. All of this has me walking the fine line between stereotypes and social acceptance.

I also struggle because the biggest proponents of gender stereotypes, the biggest consumers of gender-typed toys, media, and clothes, are the caring, sweet women who love my children dearly. I have been blessed with parents and in-laws who are wonderful people. They are a challenge because they are kind people who mean no harm. One mother-in-law now just attaches the receipt with every gift in case I want to return it. So I try to edit out gender stereotypes without offending people. I can handle being thought of as weird, but I never want to be thought of as rude.

To back up a bit, I didn’t start out this way. When I first got married, I didn’t pay much attention to gender. I was young and childless and a recent college graduate. I was working with at-risk children in inner city schools and trying to figure out what I wanted to study in graduate school. And then my life changed on a Saturday afternoon at McDonald’s.

I was in the drive-thru ordering a Happy Meal when the speaker blasted, “A boy or a girl?”

“Huh?” I said (I’d been expecting a question about ketchup or napkins).

She repeated her question, clearly irritated that I wasn’t going along with the script. “Why does it matter?” I asked. “So we know what toy to put in it,” she said. At that moment, I was struck by what a pointless question this was.

I drove home with my mental wheels turning: “How does knowing if it’s a boy or girl tell you what toy a kid will like?” “Why can’t you just ask ‘Do you want the My Little Pony or Legos?’” “How often do we base our decisions on someone’s gender?” And most importantly, “Does this affect who children turn out to be?”

So, for the price of a Happy Meal, I now had a career goal. I needed to answer those questions. I went to graduate school, earned a PhD in developmental psychology, and specialized in how our obsession with gender and the differences between boys and girls affects children and their development. My eyes were opened to the many ways our society focuses on gender, even when it is irrelevant. I learned about how children socialize themselves to fit in with their same-gender group. I studied and conducted research on the damage gender stereotypes exact on boys and girls.

When I became a mom, my studies took on a whole new level of importance—and complexity. When my first child, Maya, was very young, it was easy to focus on my goal of having a stereotype-free home. Lots of time and energy went into editing out the gender stereotypes around us. I would substitute the word “kid” in books when the author wrote “boys” or “girls,” I would tear out “Peter Peter Pumpkin Eater, had a wife and couldn’t keep her” from the Mother Goose books, and I would only buy blue and green clothes to balance out all the pink clothes given to us.

My parenting style has relaxed a bit now, mainly because I also wanted to avoid making Maya the freaky social outcast who had never heard of Disney movies. My desire to raise a child without gender stereotypes was balanced by my desire to raise a child with friends and good social skills. Also, these struggles became more complex as Maya’s very stereotypically girly friends started to have a powerful influence. I remember the painful day she marched home and proudly announced that her favorite color was no longer green but pink. This change was driven more by her desire to be like her best friend, Dakota, than anything else.

With my second daughter, Grace, my commitment to gender-blind parenting took on a different flavor, mainly because Grace was so different from Maya, and the unique characteristics I wanted to foster were different. I am reminded daily of how much variability there is between children, even when both are girls. Despite their similarities, they are different at their core. But I also suffer the same kind of fatigue everyone feels with a second child. I have less energy now to edit out every stereotype I find in a book or toy. I pick and choose my battles more often.

This book bridges what I know as a developmental psychologist with what I face trying to raise children in our society. It is a look at our cultural obsession with gender. I describe the science behind why we form stereotypes, how to know when those stereotypes are accurate and when they are misguided, and how those stereotypes affect boys and girls. I also describe the difficulties—and rewards—of parenting against the norm and why I think it is ultimately worth the fight.

The book is organized in three parts. Part I describes how we use gender constantly to sort, categorize, and label children and how that affects our thinking about people, including our own kids. Part II describes how that gender focus is, more often than not, inaccurate, and how most of our presumed gender differences are really more stereotype than science. Part III describes how our focus on gender differences can actually affect our own kids in the real world, how it can limit their strengths and abilities, and how you can realistically parent with a little less focus on gender and a little more focus on your individual children (without making your mother-in-law think you are a total nut job). With this approach, children can be more secure, happier, more well-rounded, and better able to reach their full potential (and it can be a lot more fun for parents).

My goal in this book isn’t to convert everyone to my exact way of parenting. My goal is to help parents know what science really tells us about gender differences; to think about the ways parents understand and explain their children’s behavior; to spend a few extra seconds before making a decision about what activities to enroll their children in; to think twice about believing that any difference between their son and daughter is entirely due to gender; to not always say, “You know how boys are.” Basically, I hope this book can help parents recognize and foster their children’s unique strengths, even in a culture obsessed with fitting everyone into a pink or blue box.

Copyright © 2014 by Christia Spears Brown, PhD. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.