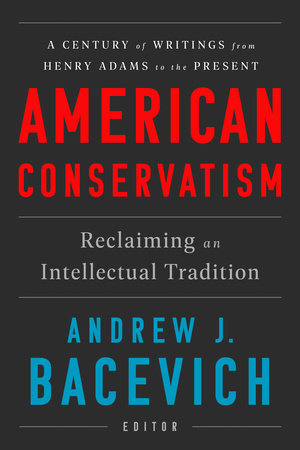

From the IntroductionThe modern American conservative tradition—roughly dating from the dawn of the twentieth century—emerged in reaction to modernity itself. Modernity meant machines, speed, and radical change—taboos lifted, bonds loosened, and, according to Max Weber, “the disenchantment of the world.” It induced, and perhaps required, centralization. States accrued power. Bureaucracies thickened. Banks, corporations, rail systems, and industrial enterprises grew to mammoth proportions. War became more destructive.

Modernity promised liberation and for many did improve the quality of everyday life. Yet it also subjected individuals to immense and only dimly comprehended forces. In exchange for choice, it demanded conformity. Modernity demolished tradition or rendered it irrelevant. What remained of the past might retain interest as artifact but was drained of substantive relevance.

Liberals, progressives, leftists—choose what label you will—have tended to embrace modernity, seeing it, on balance, as a positive force. By comparison, conservatives have typically viewed modernity as a threat, responding to it with a mixture of apprehension, alarm, and horror. This anthology collects in a single volume noteworthy examples of the American conservative critique prompted by the encroachments of modernity.

That said, I am not suggesting that in the long, contentious, at times bitter debate about America’s purpose and destiny, proponents of conservatism have necessarily gotten things right. The issues being contested are too complex to allow for reductive judgments of right or wrong, good or bad. Yet in the crisis that has enveloped twenty-firstcentury America—a crisis made starkly manifest by Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president in 2016—conservative principles deserve a second look, even, or especially, from those who bridle at the very use of the term.

Skeptics might respond that Americans today already have more than ample exposure to conservative perspectives, whether coming directly from Trump’s White House, from megaphone-wielding House and Senate Republicans, or from outlets such as FoxNews, AM talk radio, and right-wing websites. Yet all of these qualify as conservative only in the sense that blue-chip recruits at a football factory qualify as “student-athletes.” Any resemblance to the real article is superficial and manufactured.

Donald Trump is not a conservative. Nor are the leaders of the Republican Party over which Trump presides. Prominent GOP figures such as Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell seem to adhere to no worldview worthy of the name. As for the provocateurs who inhabit the sprawling universe of rightwing media, their principal motive is not to promote genuine conservative values but to rabble-rouse and line their own pockets. Indeed, allowing Trump, McConnell, Sean Hannity, Laura Ingraham, Rush Limbaugh et al. to present themselves as exemplary conservatives testifies to the pervasive corruption of contemporary American political discourse.

So except among the multitudes who sport MAGA hats and look to the likes of Sean, Laura, and Rush for instruction, the conservative brand has of late been badly tarnished and even degraded. As a result, conservatism today has become synonymous with meanness, bigotry, and retrograde attitudes. The contents of this book suggest that this condescending characterization is wildly off the mark.

Copyright © 2020 by Andrew J. Bacevich, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.