I.

THE INADEQUATE LIFE

On the morning of April 7, 1991, when my father telephonedto invite me to his apartment in Chapinero for the firsttime, there was such a downpour in Bogotá that the streamsof the Eastern Hills burst their banks, and the water camepouring down, dragging branches and mud, blocking the sewers,fl ooding the narrowest streets, lifting small cars with theforce of the current, and even killing an unwary taxi driverwho somehow ended up trapped under the chassis of his ownvehicle. The phone call itself was at the very least surprising,but on that day seemed nothing less than ominous, not onlybecause my father had stopped receiving visitors a long timebefore, but also because the image of the water- besieged city, themotionless traffic jams and broken stoplights and maroonedambulances and unattended emergencies, would have sufficedunder normal circumstances to convince anyone that goingout to visit someone was imprudent, and asking someoneto come to visit almost rash. The scenes of Bogotá in chaosattested to the urgency of his call and made me suspect thatthe invitation was not a matter of courtesy, suggesting a provisionalconclusion: we were going to talk about books. Notjust any old book, of course; we’d talk about the only one I’d then published, a piece of reportage with a TV- documentarytitle— A Life in Exile, it was called— that told or tried to tellthe life story of Sara Guterman, daughter of a Jewish familyand lifelong friend of ours, beginning with her arrival inColombia in the 1930s. When it appeared in 1988, the bookhad enjoyed a certain notoriety, not because of its subjector its debatable quality, but because my father, a professor ofrhetoric who never deigned to sully his hand with any form ofjournalism, a reader of classics who disapproved of the very actof commenting on literature in print, had published a savagereview of it in the Sunday magazine of El Espectador. It’s perhapsunderstandable that later, when my father sold the familyhome at a loss and took a lease on a refuge for the inveteratebachelor he pretended to be, I wasn’t surprised to hear thenews from someone else, even if it was from Sara Guterman,my least distant someone else.

So the most natural thing in the world, the afternoon Iwent to see him, was to think it was the book he wanted todiscuss with me: that he was going to make amends, threeyears late, for that betrayal, small and domestic though it mayhave been, but no less painful for that. What happened wasvery different. From his domineering, ocher- colored armchair,while he changed channels with the solitary digit of his mutilatedhand, this aged and frightened man, smelling of dirtysheets, whose breathing whistled like a paper kite, told me,in the same tone he’d used all through his life to recountan anecdote about Demosthenes or Gaitán, that he’d spentthe last three weeks making regular visits to a doctor at theSan Pedro Claver Clinic, and that an examination of his sixty- seven- year- old body had revealed, in chronological order,a mild case of diabetes, a blocked coronary artery— the anteriordescending— and the need for immediate surgery. Nowhe knew how close he’d been to no longer existing, and hewanted me to know, too. “I’m all you’ve got,” he said. “I’m allyou’ve got left. Your mother’s been buried for fifteen years. Icould have not called you, but I did. You know why? Becauseafter me you’re on your own. Because if you were a trapezeartist, I’d be your only safety net.” Well then, now that sufficient time has passed since my father’s death and I’ve finallydecided to organize my head and desk, my documents andnotes, to get this all down in writing, it seems obvious that Ishould begin this way: remembering the day he called me, inthe middle of the most intense winter of my adult life, not tomend the rift between us, but in order to feel less alone whenthey opened his chest with an electric saw and sewed a veinextracted from his right leg into his ailing heart.

It had begun with a routine check- up. The doctor, a man witha soprano’s voice and a jockey’s body, had told my father that amild form of diabetes was not entirely unusual or even terriblyworrying at his age: it was merely a predictable imbalance andwasn’t going to require insulin injections or drugs of any kind,but he would need to exercise regularly and observe a strictdiet. Then, after a few days of sensible jogging, the pain began,a delicate pressure on his stomach, rather resembling a threatof indigestion or something strange my father might haveswallowed. The doctor ordered new tests, still general ones but more exhaustive, and among them was a test of strength; myfather, wearing underpants as long and baggy as chaps, firstwalked then jogged on the treadmill, and then returned tothe tiny changing room (in which, he told me, he’d felt likestretching his arms, and, realizing the place was so small hecould touch the facing walls with his elbows, suffered a briefattack of claustrophobia), and when he’d just put on his flanneltrousers and begun to button up the cuffs of his shirt,already thinking about leaving and waiting for a secretary tocall him to pick up the results of his electrocardiogram, thedoctor knocked on the door. He was very sorry, he said, buthe hadn’t liked what he’d seen in the initial results: they weregoing to have to do a cardiac catheterization immediately toconfirm the risks. And they did, of course, and the risks (ofcourse) were confirmed: there was an obstructed artery.

“ Ninety- nine percent,” said my father. “I would have had aheart attack the day after tomorrow.”

“Why didn’t they admit you there and then?”

“Because the fellow thought I looked really nervous, I suppose.

He thought it’d be better if I went home. He did giveme a very specific set of instructions, though. Told me not tomove all weekend. Avoid any kind of excitement. No sex atall, especially. That’s what he said to me, believe it or not.”

“And what did you say to him?”

“That he didn’t need to worry about that. I wasn’t about totell him my life story.”

As he left the office and hailed a taxi amid the confusionof Twenty- sixth Street, my father had barely begun to confrontthe idea that he was ill. He was going to be admitted to the hospital without a single symptom that would betraythe urgency of his condition, with no discomfort beyond thefrivolous pain in the pit of his stomach, and all because of anincriminating catheter. The doctor’s arrogant spiel kept runningthrough his head: “If you’d waited three more days beforecoming to see me, we’d probably be burying you in a week.” Itwas a Friday; the operation was scheduled for the followingThursday at six in the morning. “I spent the night thinking Iwas going to die,” he told me, “and then I phoned you. Thatsurprised me, of course, but now I’m even more surprised you’vecome.” It’s possible he was exaggerating: my father knew noone was apt to consider his death as seriously as his own son,and we devoted that Sunday afternoon to such considerations.

I made a couple of salads, made sure there was juice and waterin the fridge, and began to look over his latest income- taxreturn with him. He had more money than he needed, whichisn’t to say he had a lot, just that he didn’t need much. His onlyincome came from his pension from the Supreme Court, andhis capital— that is, the money he’d received when he’d sold offthe house where I’d grown up and my mother had died— hadbeen invested in savings bonds, and the interest from themwas enough to cover his rent and living expenses for the mostascetic lifestyle I’d ever seen: a lifestyle in which, as far as Icould tell, no restaurants, concerts, or any other means, moreor less onerous, of entertainment entered into the picture. I’mnot saying that if my father had spent the occasional nightwith a hired lover I would have found out about it; but whenone of his colleagues tried to get him out of the house, to takehim out for a meal with some woman, my father refused once and then left the phone off the hook for the rest of the day.

“I’ve already met the people I had to meet in this life,” he toldme. “I don’t need anyone new.” One of those times, the personwho invited him was a trademark and patents lawyer youngenough to be his daughter, one of those large- breasted girlswho don’t read and seem to go through an inevitable phaseof curiosity about sex with older men. “And you turned herdown?” I asked. “Of course I turned her down. I told her Ihad a political meeting. ‘What party?’ she asked. ‘The OnanistParty,’ I told her. And off she went quietly home and neverbothered me again. I don’t know if she found a dictionary intime, but she seems to have decided to leave me alone becauseshe hasn’t invited me to anything since. Or who knows, maybethere’s a lawsuit against me, no? I can almost see the headlines:PERVERTED PROFESSOR ASSAULTS YOUNG WOMAN WITHBIBLICAL POLYSYLLABLES.”

I stayed with him until six or seven and then went home,thinking during the whole trip about what had just happened,about the strange twist of a son’s seeing his father’s home forthe first time. Was it just the two rooms— the living roomand bedroom— or was there a study somewhere? I couldn’tsee more than a cheap white bookcase leaning carelesslyagainst the wall that ran parallel to Forty- ninth Street, besidea barred window that hardly let in any light. Where were hisbooks? Where were the plaques and silver trays with whichothers had insisted on distinguishing his career over the years?Where did he work, where did he read, where did he listen tothat record— The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, a title I wasn’tfamiliar with— the sleeve of which was lying on the kitchen table? The apartment seemed stuck in the 1970s: the orangeand brown carpet; the white fiberglass chair I sank into asmy father recalled and described for me the map of his catheterization(its narrow highways, its back roads); the closed,windowless bathroom, lit only by a couple of transparent plasticrectangles on the ceiling (one of which was broken, andthrough the hole I could see two neon tubes in their deaththroes). There was soapy foam in the green washbasin, theshower was dark and didn’t smell too good, and from its aluminumframe hung two pairs of recently washed underpants.Had he washed them himself? Didn’t anyone come to helphim? I opened drawers and doors held shut with magnets andfound some aspirin, a box of Alka- Seltzer, and a rusty shavingbrush that no one had used for a long time. There were dropsof urine on the toilet bowl and on the fl oor: yellow, smellydrops, telltale signs of a worn- out prostate. And there, on topof the tank, under a box of Kleenex, was a copy of my book.

I wondered, of course, if this might not be his way of suggestingthat his opinion had not changed over the years. “Journalismaids intestinal transit,” I imagined him telling me. “Didn’tthey teach you that at the university?”

When I got home I made a few calls, although it was toolate to cancel the operation or to pay any attention to secondopinions, especially those formulated over the phoneand without the benefit of documents, test results, and X- rays.In any case, talking to Jorge Mor, a cardiologist at the ShaioClinic who’d been a friend of mine since school, didn’t domuch to calm me down. When I called him, Jorge confirmedwhat the doctor at San Pedro Claver had said: he confirmed the diagnosis as well as the necessity of operating urgently,and also the luck of having discovered the matter by chance,before my father’s asphyxiated heart did what it was thinkingof doing and suddenly stopped without warning. “Rest easy,brother,” Jorge told me. “It’s the simplest version of a difficultoperation. Worrying from now till Thursday won’t do anyoneany good.” “But what could go wrong?” I insisted. “Everythingcan go wrong, Gabriel, everything can go wrong in any operationin the world. But this is one that’s got to be done, and itis relatively simple. Do you want me to come over and explainit to you?” “Of course not,” I said. “Don’t be ridiculous.” Butmaybe if I’d accepted his offer I would have kept talking toJorge until it was time to go to bed. We would have talkedabout the operation; I would have gone to sleep late, after oneor two soporific drinks. Instead, I ended up going to bed atten, and just before three in the morning I realized I was stillawake and more frightened than I’d thought.

I got out of bed, felt in the pockets of my jeans for theshape of my wallet, and dumped its contents into the pool oflamplight. A few months before I turned eighteen, my fatherhad presented me with a rectangular card, dark blue on oneside and white on the other, which gave him the right to beburied with my mother in the Jardines de Paz— and there wasthe cemetery’s logo, letters like lilies— and asked me to keepit in a safe place. At that moment, like any other teenager, Icouldn’t think of anywhere better to put it than in my wallet;and there it had stayed all that time, between my ID cardand my military card, with its funereal aspect and the nametyped on an adhesive strip now wearing away. “One never knows,” my father had said when he gave it to me. “We couldget blown up any day and I want you to know what to do withme.” The time of bombs and attacks, a whole decade of livingevery day with the knowledge that arriving home each nightwas a matter of luck, was still in the distance; if he had infact been blown up, the possession of that card wouldn’t havemade things any clearer to me as to how to deal with the dead.Now it struck me that the card, yellowed and worn, lookedlike the mock- ups that come in new wallets, and no strangerwould have seen it for what it actually was: a laminated tomb.And so, considering the possibility that the moment to use ithad arrived, not due to any bombs or attacks but through thepredictable misdeeds of an old heart, I fell asleep.

They admitted him at five o’clock the next afternoon.Throughout those first hours, already in his green dressinggown, my father answered the anesthesiologist’s questionsand signed the white Social Security forms and the tricolorlife insurance ones (a faded national fl ag), and throughoutTuesday and Wednesday he spoke and kept speaking,demanding certainties, asking for information and in histurn informing, sitting on the high, regal mattress of the aluminumbed but nevertheless reduced to the vulnerable positionof one who knows less than the person with whom he’sspeaking. I stayed with him those three nights. I assured him,time and time again, that everything was going to be fine. Isaw the bruise on his thigh in the shape of the province ofLa Guajira, and assured him that everything was going tobe fine. And on Thursday morning, after they shaved hischest and both legs, three men and a woman took him to the operating room on the second fl oor, lying down and silent forthe first time and ostentatiously naked beneath the disposablegown. I accompanied him until a nurse, the same one who’dlooked blatantly and more than once at the patient’s comatosegenitals, asked me to get out of the way and gave me a littleammonia- smelling pat, saying the same thing I’d said to him:“Don’t worry, sir. Everything’s going to be fine.” Except sheadded, “God willing.”

Almost anyone would recognize my father’s name, and notonly because it’s the same as the one on the front of this book(yes, my father was a perfect example of that predictable species:those who are so confident of their life’s achievementsthat they have no fear of baptizing their children with theirown names), but also because Gabriel Santoro was the manwho taught, for more than twenty years, the famous Seminaron Judicial Oratory at the Supreme Court, and the man who,in 1988, delivered the commemoration address on the fourhundred and fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Bogotá,that legendary text that came to be compared with the finestexamples of Colombian rhetoric, from Bolívar to Gaitán.gabriel santoro, heir to the liberal caudillo, was theheadline in an official publication that few know and no onereads, but which gave my father one of the great satisfactionsof his life in recent years. Quite right, too, because he’d learnedeverything from Gaitán: he’d attended all his speeches; he’dplagiarized his methods. Before he was twenty, for example,he’d started wearing my grandmother’s corsets to create the same effect as the girdle that Gaitán wore when he had tospeak outdoors. “The girdle put pressure on his diaphragm,”my father explained in his classes, “and his voice would comeout louder, deeper, and stronger. You could be two hundredmeters from the podium when Gaitán was speaking with nomicrophones whatsoever, pure lung power, and you could hearhim perfectly.” The explanation came accompanied by thedramatic performance, because my father was an excellentmimic (but where Gaitán raised the index finger of his righthand, pointing to the sky, my father raised his shiny stump).“People of Colombia: For the moral restoration of the Republic!People of Colombia: For your victory! People of Colombia:For the defeat of the oligarchy!” Pause; ostensibly kindquestion from my father: “Who can tell me why this series ofphrases moves us, what makes it effective?” An incautious student:“We’re moved by the ideas of— ” My father: “Nothingto do with ideas. Ideas don’t matter, any brute can have ideas,and these, in particular, are not ideas but slogans. No, theseries moves and convinces us through the repetition of thesame phrase at the beginning of the clauses, something thatyou will all, from now on, do me the favor of calling anaphora.And the next one to mention ideas will be shot.”

I used to go to these classes just for the pleasure of seeinghim embody Gaitán or whomever (other more or less regularcharacters were Rojas Pinilla and Lleras Restrepo), and I gotused to watching him, seeing him squaring up like a retiredboxer, his prominent jaw and cheekbones, the imposing geometryof his back that filled out his suits, his eyebrows so longthey got in his eyes and sometimes seemed to sweep across his lids like theater curtains, and his hands, always and especiallyhis hands. The left was so wide and the fingers so long that hecould pick up a football with his fingertips; the right was nomore than a wrinkled stump on which remained only the mastof his erect thumb. My father was about twelve, and alone in hisgrandparents’ house in Tunja, when three men with machetesand rolled- up trousers came in through a kitchen window,smelling of cheap liquor and damp ponchos and shouting “Death to the Liberal Party,” and didn’t find my grandfather,who was standing for election to the provincial government ofBoyacá and would be ambushed a few months later in Sogamoso,but only his son, a child who was still in his pajamaseven though it was after nine in the morning. One of themchased him, saw him trip over a clump of earth and get tangledup in the overgrown pasture of a neighboring field; after oneblow of his machete, he left him for dead. My father had raiseda hand to protect himself, and the rusty blade sliced off his fourfingers. María Rosa, the cook, began to worry when he didn’tshow up for lunch, and finally found him a couple of hours afterthe machete attack, in time to stop him bleeding to death. Butthis last part my father didn’t remember; they told him later,just as they told him about his fevers and the incoherent thingshe said— seeming to confuse the machete- wielding men withthe pirates of Salgari books— amid the feverish hallucinations.

He had to learn how to write all over again, this timewith his left hand, but he never achieved the necessary dexterity,and I sometimes thought, without ever saying so, thathis disjointed and deformed penmanship, those small child’scapital letters that began brief squadrons of scribbles, was the only reason a man who’d spent a lifetime among other people’sbooks had never written a book of his own. His subject was theword, spoken and read, but never written by his hand. He feltclumsy using a pen and was unable to operate a keyboard: writingwas a reminder of his handicap, his defect, his shame. Andseeing him humiliate his most gifted students, seeing him fl ogthem with his vehement sarcasm, I used to think: You’re takingrevenge. This is your revenge.

But none of that seemed to have any consequences in thereal world, where my father’s success was as unstoppable as slander.The seminar became popular among experts in criminallaw and postgraduate students, lawyers employed by multinationalsand retired judges with time on their hands; and therecame a time when this old professor with his useless knowledgeand superfl uous techniques had to hang on the wall, betweenhis desk and bookshelves, a kind of kitsch, colonial shelf, uponwhich piled up, behind the little rail with its pudgy columns, thesilver trays and the diplomas on cardboard, on watermarkedpaper, on imitation parchment, and the particleboard plaqueswith eye- catching coats of arms in colored aluminum.

FOR GABRIEL SANTORO, IN RECOGNITION OF TWENTYYEARS OF PEDAGOGICAL LABOR . . . CERTIFIES THAT DOCTORGABRIEL SANTORO, BY VIRTUE OF HIS CIVIL MERITS . . .THE MAYORALTY OF GREATER BOGOTÁ, IN HOMAGE TODOCTOR GABRIEL SANTORO . . .

There, in that sort of sanctuary for sacred cows, the sacred cowwho was my father spent his days. Yes, that was his reputation: my father knew it when they called him from city hall to offerhim the speech at the Capitolio Nacional; that is, to ask himto deliver a few commonplaces in front of bored politicians.

This peaceable professor— they would have thought— tickedall the right boxes for the event. My father didn’t give themanything they expected.was in each one of those sentences— all of which, I’m sure,held no importance for my father, who wanted only to dust offhis rifl es and take his best shots in the presence of a select audience.None of them, however, could recognize the value of thatexemplary model of rhetoric: a valiant introduction, becausehe relinquished the chance to appeal to his audience’s sympathies(“I’m not here to celebrate anything”), a narrative basedon confrontation (“This city has been betrayed. Betrayed byall of you for almost half a millennium”), an elegant conclusionthat began with the most elegant figure of classical oratory(“There once was a time when it was possible to speak of thiscity”). And then that final paragraph, which would later serveas a mine of epigraphs for various official publications and wasrepeated in all the newspapers the way they repeat Simón Bolívar’sI shall go quietly down to my grave or Colonel, you must saveour nation.

Somewhere in Plato we read: “Landscapes and treeshave nothing to teach me, but the people of a city mostcertainly do.” Citizens, I propose we learn from ours, Ipropose we undertake the political and moral reconstructionof Bogotá. We shall achieve resurrectionthrough our industry, our perseverance, our will. On herfour hundred and fiftieth birthday, Bogotá is a young cityyet to be made. To forget this, citizens, is to endanger ourown survival. Do not forget, citizens, nor let us forget.

My father spoke about reconstruction and morals and perseverance,and he did so without blushing, because he focused less on what he said than on the device he used to say it. Laterhe would comment: “The last sentence is nonsense, but thealexandrine is pretty. It fits nicely there, don’t you think?”

The whole speech lasted sixteen minutes and twentyseconds— according to my stopwatch and not including the ferventapplause— a tiny slice of that August 6, 1988, when Bogotáturned four hundred and fifty, Colombia celebrated one hundredand sixty- nine years less a day of independence, my motherhad been dead for twelve years, six months, and twenty- onedays, and I, who was twenty- seven years, six months, and fourdays old, suddenly felt overwhelmingly convinced of my owninvulnerability, and everything seemed to indicate that therewhere my father and I were, each in charge of his own successfullife, nothing could ever happen to us, because the conspiracyof things (what we call luck) was on our side, and from then onwe could expect little more than an inventory of achievements,ranks and ranks of those grandiloquent capitals: the Pride ofour Friends, the Envy of our Enemies, Mission Accomplished.I don’t have to say it, but I’m going to say it: those predictionswere completely mistaken. I published a book, an innocentbook, and then nothing was ever the same again.

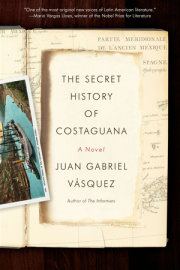

Copyright © 2009 by Juan Gabriel Vasquez. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.