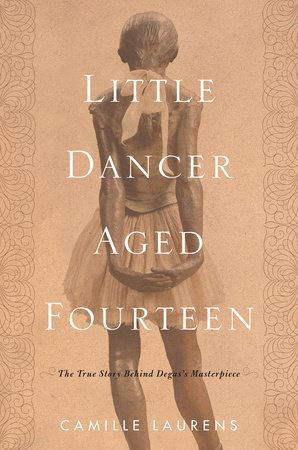

SHE IS FAMOUS THE WORLD OVER, but how many people know her name? You can admire her in Washington, Paris, London, New York, Dresden, and Copenhagen, but where is her grave? All we know is her age, fourteen, and the work she did, because it truly was work, at an age when our own children are attending school. In the 1880s, she danced as a little rat (as girls in training for the corps de ballet were known) at the Paris Opera, and what seems like a dream to many of our young girls today was not a dream to her, not the happy age of youth.

L’Age heureux was the name of a television show when I was growing up

, it featured young ballet students at the Paris Opera doing silly things. They climbed onto the roof of the Palais Garnier, I remember, and you were afraid something terrible would happen to them, a fall or expulsion from the program, because discipline was very strict. I don’t remember how it all ended — happily, no doubt, given the show’s title.The little dancer of 1880, though, was sent home after a few years’ work, when the director grew tired of seeing her miss rehearsal — eleven times in the last trimester alone.

But the reason was that she had another job, possibly two other jobs, because the pittance she earned at the Paris Opera was not enough to feed her and her family. She was an artist’s model, posing for painters and sculptors. Among them was Edgar Degas. Did she know as she posed in his studio that, thanks to him, she would die less completely than the other girls? Stupid question — as though the work counted for more than the life. It would have been no feather in her cap to know that, a century after her death, people would still be buzzing around her in the high-ceilinged halls of museums just as the fine gentlemen in the foyer of the Paris Opera did, that she would still be examined up and down and from all sides, just as she was in the seamy dives where she may have sold her body on orders from her mother — her frail body, now turned to bronze. But maybe it did make a difference, maybe she did think about it sometimes. Who can say? Surely she had heard how the

Mona Lisa was taken to safety during the Franco-Prussian War, how it was returned to the Louvre after France’s defeat, how everyone in Paris was visiting it admiringly and buying it in reproduction, thanks to the new reprographic techniques. When she posed for her employer for hours on end, growing tired in what was supposedly a “rest” position, one leg forward, hands clasped behind her back, silent, did she consider that Monsieur Degas had enough talent to make her famous too, that her little walk-on role would one day make her a star? Did she imagine such a future for herself — a fame that the ballet world would never grant her? It’s possible. After all, little girls do have their dreams.

What I hope, as I look at her in triptych on a postcard — back, front, and profile — bought at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is that she was oblivious to all that was said about her during the first exhibition of the

Little Dancer. Although it wasn’t exactly said about her. Do you know the story of Cézanne’s portrait of his wife? Some people stopped in front of it and said, “What a hag!” while others said, “What a masterpiece!” Which counts for more, the painting or the model, art or nature? Does the work of art console us for what happens in life? Certainly, the little dancer was not expounding on the relation between actuality and representation. Nor was anyone else. On that April day in 1881 when the figure was first exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, there were few who made the distinction. Esthetes and society ladies, critics and amateurs, all crowded together in front of the sculpture, made more impatient by the fact that the sculpture had been announced for last year’s show but inexplicably withdrawn. And this year, Degas had brought it to the exhibition late, fourteen days after the opening. An empty glass case, the subject of much speculation, stood in as a placeholder, while rumors circulated that the sculpture would not be in marble or bronze, nor even in plaster or wood, but in wax. Normally, wax is a stage in the process of making the final work, but the artist was choosing here to exhibit it as the end product. And

it would be dressed in real clothes, like a doll. Wearing actual ballet slippers. What an oddity! All the same, this wasn’t the official Salon but the exhibition mounted by the splinter group of the Indépendants, the so-called Impressionists, who had never been very academically minded, so it wasn’t all that surprising. Other than a portrait carved in wood and a small bronze by Paul Gauguin,

La Petite Parisienne, Degas’s

Little Dancer was the only sculpture in the show. Finally, the public was getting a chance to see it! In the midst of canvases by Pissarro, Cassatt, Gauguin, the figure stood in a glass case, which further piqued curiosity. They pressed forward eagerly, approaching their faces, their monocles, to the transparent divider; they frowned, they backed away, what the devil, hesitated, and either fled or stood transfixed. Almost all who saw it, sensitive and cultured as they were, reacted with horror to the

Little Dancer. This isn’t art! some people said. What a monster! said others. An abortion! An ape! She would look better in a zoological museum, opined a countess. She has the depraved look of a criminal, said another. “How very ugly she is!” said a young dandy. “She’ll do better as a rat at the Opera than as a pussy at the bordello!” One journalist wondered, “Does there

truly exist an artist’s model this horrid, this repulsive?” A woman essayist for the British review

Artist described her as looking “half idiotic,” “with her Aztec head and expression.” “Can Art descend any lower?” she asked. Such depravity! Such ugliness! The work and the model were conjoined in a single tide of disapproval, a wave of hostility and hatred whose virulence surprises us today. “This barely pubescent little girl, a flower of the gutter,” had made her entry into the history of artistic revolutions.

Once on view, the

Little Dancer was exposed — as was the little dancer who modeled for Degas — to public stares and condemnation, to esthetic tastes and moral distaste. Both the sculpture and the girl came in for more contempt than admiration on that day. No one had asked her, a poor girl whose body was her only asset, for permission to put her at risk — at risk of displeasing and being demeaned. The shame of humiliation. It’s true that in all likelihood she was not invited to the Salon des Indépendants. She probably never visited the sculpture during the exhibit’s three-week run on the boulevard des Capucines, not far from the Paris Opera. One or another of the ruffians and grisettes she associated with, however, may have passed along the news in mocking tones: “Everyone is running off to admire you. Are you really the new Mona Lisa?” But her modeling sessions for Degas were already a distant memory. So many things had happened since, and she was now sixteen. What was the point in looking back? Besides, the exhibition hall wasn’t open to the poor, to working-class women, or to prostitutes. No one congratulated a model for her patience, her immobility, her selflessness. Possibly for her beauty, if she was the artist’s mistress. But that was all. Marie had not slept with Degas, as far as we know. She hadn’t read the accounts in the

newspapers either — she’d been obliged to leave school early and barely knew how to read or write. The sculpture received few favorable reviews. The nicest came from Nina de Villard, companion to the poet Charles Cros, who visited the exhibition and wrote: “I felt before this statuette one of the strongest artistic sensations I’ve ever experienced: I have long been dreaming of exactly this.” Marie wouldn’t have seen the review. And no one would have read her Huysmans’s encomiums, directed at the artist in any case, not at her. The critic praised Degas for acting boldly, for overthrowing all the conventions of sculpture, “all the models endlessly recopied over the centuries” to produce a work “so original, so fearless . . . truly modern.” But Huysmans was pitiless in his description of the little dancer, with her “sickly, grayish face, old and drawn before its time.” I like to think that in posing for the great artist with that defiant air, which the critic Paul Mantz characterized in the following day’s

Le Temps as “bestial effrontery,” Marie foresaw the scandalized reaction of the moneyed set and responded to it in advance with that look of insolent detachment. And I like to believe that it speaks of her freedom, rising above all hindrances, a twin to Degas’s own, yet very much hers, calm and nearly smiling, chin up, her personal freedom.

When the stormy Salon of 1881 closed, Degas brought his

Little Dancer home and never showed it again to anyone. It didn’t travel to the great Impressionist exhibition organized by Durand-Ruel in New York in 1886. It gathered dust in a corner of the studio, visibly darkening, piled up among other sculptures, its tutu in shreds, next to ballet slippers and photographs of dancers. But the sculpture still figured in the thoughts of Degas’s contemporaries. In the 1890s, Henri de Régnier and Paul Helleu would discuss the

Little Dancer with the poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Artists such as Maurice Denis, Georges Rouault, and Walter Sickert mentioned it long after its disappearance from view. In 1903, Louisine Havemeyer, a shrewd American collector and future suffrage activist, offered to buy it from the artist: the scandalous

Little Dancer, by her absence, had become cloaked in mystery, a legend. Degas refused. He wanted neither to sell the sculpture nor to have it seen. Mrs. Havemeyer, on advice from Mary Cassatt, repeated her offer several times, but Degas resisted the pressure and kept his small statue. He reworked it a little, pondered the possibilities, returned to it: “I must finish this sculpture, even if it puts my aged life at risk. I’ll continue till I drop — and I still feel quite steady on my pegs, despite having just turned sixty-nine,” he wrote in a letter dated to the summer of 1903. Friends suggested that he have bronze casts made, since wax was eminently fragile. Either Degas lacked the funds to do this, having by this time lost his fortune, or he wanted to stay in tête-à-tête with the original — or both — but he never followed up on the suggestion. Possibly he was applying to his own work an observation he had once made on a Rembrandt painting that the Louvre planned to restore: “Touch a painting! But a painting is meant to die, time is meant to walk over it, as over everything else, whence its beauty.”

It was only after his death in 1917 that more than 150 wax statuettes, found at his home in a greater or lesser state of deterioration, were given conservation treatment, the

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen among them. But Degas’s close circle did not let time walk over the

Little Dancer. After hesitating about whether to restore it for sale as a unique piece, the family decided to send it to the A. A. Hébrard foundry in Paris. There, thanks to the painter Paul-Albert Bartholomé, a friend of Degas, twenty-two bronze casts of the

Little Dancer were made, after an initial plaster mold, then patinated to better imitate the original wax, and finally dispersed to various museums and private collections. This quick and dirty decision by Degas’s heirs, which showed little respect for the artist’s personality and wishes, was seen by some as a betrayal. Yet making reproductions of the original did not, as Mary Cassatt had feared, detract from the work’s artistic value, and the casts were remarkably faithful. Looking at auction catalogs, we learn that one cast, which included the original clothes, was sold in 1971 for $380,000. Another was auctioned at Sotheby’s for more than £13 million. The work has inspired investors. At the start of the twenty-first century, Sir John Madejski, owner of the Reading Football Club, bought the sculpture for £5 million and sold it five years later for £12 million. We won’t editorialize on the gross unfairness of the worlds of art and finance, knowing how many painters ended up in mass graves whose works now slumber in safe-deposit vaults.

Degas always lived off his painting. He was also a voracious collector — Ingres, Delacroix, Manet, Pissarro, Daumier, Corot, Sisley, Hokusai,Van Gogh. At his death, he owned, warehoused in his home, more than five hundred masterpieces and thousands of lithographs. But he despised money. His father was a banker who had gone through bankruptcy, and Degas hated to see a work of art treated as a “luxury item” when to him it was an “item of primary necessity.” He sold single pieces — grudgingly and at high value — when he needed the money, and he mocked his colleagues fiercely for pursuing medals, honors, and emoluments. When it came to the

Little Dancer, the administrators of the French national museums paid scant attention to the original wax version: it was allowed to leave the country for $160,000. Bought in 1956 by an American citizen, Mr. Paul Mellon, it has been in the United States ever since, a development Degas might have approved of, since he himself spent time in Louisiana, where his mother was born and a part of his family lived. He adored sprinkling his conversation with English words and would probably not have objected to the expatriation of his work, having considered emigrating himself at one point. In Paris, only one posthumous bronze casting with tutu and ribbon is on view — at the Musée d’Orsay. You can always pick up a reproduction in synthetic resin on the Internet for twenty dollars or so. And there are postcards, of which I have bought many over the years, long before I ever planned to write this book, just because I liked the little dancer. I’ve always liked her, she intrigues and moves me. Her image has accompanied me for a long time, it sits on my desk, my shelves. She has her nose in the air, not looking at me, but I feel her close all the same, observing me though in a different way. Every time I enter a museum where she is on view and to which, for some still secret reason, I’ve come expressly to see her, I feel my heart leap.

Copyright © 2018 by Willard Wood. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.