Chapter 1

Who died? On the surface, it’s relaxed. There was a time when we all dressed crisply, but something’s changed this summer. Now while the weather lasts we wear loose pants, canvas sneakers, clogs. Pru slips on flip-flops under her desk. It’s so hot out and thus every day is potentially casual Friday. We have carte blanche to wear T-shirts featuring the comical logos of exterminating companies, advertising slogans from the early ’80s. Where’s the beef? We dress like we don’t make much money, which is true for at least half of us. The trick is figuring out which half. We go out for drinks together one or two nights a week, sometimes three, to take the edge off. Three is too much. We make careful note of who buys a round, who sits back and lets the booze magically appear. It’s possible we can’t stand each other but at this point we’re helpless in the company of outsiders. Sometimes one of the guys will come to work in a coat and tie, just to freak the others out. On these days the guard in the lobby will joke, Who died? And we will laugh or pretend to laugh.

The Sprout

In summer the Sprout, our boss, suggests we form a softball team. His name is actually Russell. We refer to him as the Sprout, because

Russell ->Brussels->brussels-> sprouts-> the Sprout.

No one knows who came up with the name first.

We’re incredibly mature.

Also once in a while he has a bit of comb-proof hair sprouting from his scalp’s left rear quadrant.

Jonah says it’s hard to take the Sprout seriously because he’s always using i.e. and e.g. in his sentences, vigorously but interchangeably, a mark of weak character.

He sometimes gives us little salutes when he sees us in the hall. Lately he’s been flashing the peace sign. Sixty-five percent of the time he acts like he’s our friend but we should remember the saying:

Friends don’t fire friends. Sticks and carrots Sixty-five percent of the time is what the Sprout would call a

guesstimate. He’s always breaking things down into precise percentages. He used to be almost normal to talk to, but now he’ll ask if we’re on the

same page and say something is a no-brainer, all in a single sentence. It’s not just the frequency of these expressions but their haphazard use. Last week he told Laars to think outside the box. They were talking about which size manila folders worked best. Afterward he said,

Keep me in the loop and let’s touch base next week. Pru has wondered if the Sprout, a proud native of Canada, is taking a class in annoying American English. His new thing is a variation on

I gave you a carrot,

but I also need to show you the stick. So far this month, he’s said it to Pru, to Jack II, to Laars.

So show us already, Pru complains to Lizzie.

The Sprout understands that it sounds a little sadistic, and lets us know he recognizes this menacing aspect, at the same time wanting us to understand that he doesn’t actually mean it in that way. Jonah’s take on it is that he must mean it in that way, or else he’d use another phrase.

A league record Softball is a morale-boosting carrot that the Sprout most likely has read about in a handbook or learned at that seminar he goes to every March. Morale has been low since the Firings began last year. Pru says morale is a word thrown around only in the context of its absence. You never look at a hot young thing and say, Check out that spring chicken, but only use it to describe your great-aunt: She’s no spring chicken.

Pru has a point. We tend to trust her, with her serious eyebrows and inevitable skeptical hmmm. She went to graduate school. We think it was in art history, but maybe it was regular history, the kind without the art.

We decide to give softball a shot. There are eight of us. In decreasing order of height: Laars, Jack II, Lizzie, Jonah, Jenny, Crease, Pru, Jill. We need a ninth, and Jack II happens to bump into Otto, who used to be in IT. He is now working somewhere in midtown and clearly has too much time on his hands.

It might be nice to rejuvenate our comically untoned bodies. Too many of us have been eating bagels at our desks, too many mornings in a row. We look like we’ve been squeezed out of a tube and haven’t quite solidified. Everyone has issues with posture except Lizzie, a corseter’s dream.

Laars and Jenny are the only ones who have ever played softball before—Laars at his last job, Jenny as a seven-year-old. The concept: You try to hit the ball hard but without so much upward arc that someone can catch it. Then you run in a square, or more properly a diamond, making sure to step on each base and not get tagged by someone bearing the ball. There are other rules that we never quite iron out.

Lizzie is having trouble seeing the carrot aspect of the game.

We buy mitts, glove oil, cleats. Laars buys two aluminum bats and two wooden ones. He buys a third kind of bat, a titanium hybrid that looks like a nuclear warhead. Laars can be seen doing push-ups near the storage area, counting off under his breath.

We have jerseys and caps printed with our emblem, a buxom elf winking and holding a pool cue. Jill found it on some Finnish clip-art site.

We prematurely end our season after losing the first game 17–0, said to be a league record. What’s left of our morale seeps away. We never see Otto again. All the gear gets returned, except the jerseys and caps. Autumn approaches, the air too cool for the jerseys, but we still wear the hats sometimes.

The cult of Maxine Maxine never officially joined the softball team but bought a jersey from Jill, cutting the collar to create a plunging V. She still wears it on occasion, even as the weather turns nippy.

Maxine towers over us in her medium heels. She makes us feel like hobbit-folk, with our stained teeth and ragamuffin outfits. With the exception of Laars, we have zero upper body strength. We are moderately proud of our youthful haircuts and overpriced rectangular eyeglasses but that’s about it.

She smells great and we are all basically obsessed with her. It has to seriously stop, Lizzie says. Crease calls her aggressively hypnotic and can hardly bear to be within a twenty-yard radius. He sometimes crosses himself after she passes.

Her hair! Jack II will e-mail, out of the blue. Everyone knows whose hair he’s talking about.

Sharing an elevator ride alone with Maxine can be intensely disorienting. We try to avoid it. Several times of late, while waiting for the elevator at the end of the day, Crease has sensed Maxine’s approach, her distinctive shoe-clack sending him darting in the other direction. In similar situations, Jenny has been known to mumble to herself, giving the impression that she’s forgotten something at her desk. Jenny likes boys but sometimes when Maxine is in the room she’s not so sure.

Laars says Maxine smells like the exquisite blossom of a rare hybrid fruit that you can only find at this one stall in a market in Kuala Lumpur.

The worst is when you turn the corner and you see her and you want to say Hi in a normal way but all that happens is your mouth opens and you make a little croaking sound or make no noise at all. It was Jules, no longer among us, who first identified this phenomenon.

There is so much to take in. Not just her clothes or lack of clothes, not just her amazing hair, but her entire philosophy of being. You can detect an aspect of the beauty queen in her looks and high-gloss appearance, her attention-yanking laugh and borderline moronic statements. But Pru has argued, in the landmark case Pru v. Jonah, that she’s not only not stupid but definitely more accomplished than the rest of us. We don’t know what’s on that résumé, but it doesn’t matter—she’s got that magic, that spark, utterly unclouded by self-doubt.

Maxine is on a different track than the rest of us. She entered the office at a higher level and we’ll never catch up. By the time we reach her current position—in the event we haven’t burned out, drifted away—she’ll have scaled even greater heights, afloat on a cloud of boundless confidence and even more tantalizing scents. All of this should be illustrated in the manner of a medieval vision of the afterlife.

Lizzie is lying Empirically speaking, Maxine’s not so hot, according to Lizzie, the nicest of us. This is what passes for dissent in our little group. I seriously don’t see the appeal.

In time Lizzie comes to share our fascination, albeit in a different way. For Lizzie what’s interesting is the phenomenon of Maxine worship, rather than her actual qualities. She compares it to when we all obsessed over that reality show in which ambitious people our age backstabbed and slept with each other in order to become chefs at an exclusive French restaurant, and then the restaurant turned out not to exist.

Let’s not and say we did Maxine’s latest e-mail bears the subject line Let’s Talk About SEX.

No, moans Pru, dreading yet another sexual-harassment seminar. We never had one before Maxine came to the company. The seminars produce the opposite of the intended effect, making us feel like sex maniacs, but at least they’re better than the mental health seminars the Sprout used to hold. Those made us depressed, even violent—Laars once punched the wall by the bulletin board so hard that his hand has never been the same. He blames this injury for his subpar softball performance.

Today Maxine makes wanton eye contact with the seminar leader, a lawyer named George. She’s wearing a sheer shirt known commonly as that shirt. Pru knows the brand and everything.

George looks like he’s just come back from vacation and is about to go on another one. His relaxed manner is exhausting to contemplate. All of us secretly wonder why we didn’t go to law school, and also whether it’s too late.

It is.

The gist of the meeting is that you should never date anyone in the office, ever. You should also be extremely careful about what you say to someone of the opposite or indeed the same sex. Many seemingly harmless sentences, phrases, even words, and actually individual letters can be construed as harassing. Never say anything about what somebody’s wearing. Also, just to be safe, don’t wear anything too revealing.

We all frown and gaze at Maxine in her flesh-colored mesh number. The hypocrisy, the everything, is too much.

Jonah says,

Don’t we need eros in order for commerce to happen? in that affected pensive tone he sometimes adopts, a pause every two words.

Do we? Admittedly, it’s a stumper. None of us really knows. He sits up straight, strokes his chin in agitation. The tips of his ears go scarlet with rage. He should have been a philosophy professor or a union organizer for sooty paperboys. He says that, by the logic of the seminar, the subject line of Maxine’s e-mail constitutes sexual harassment of sorts. He slaps the table—case closed!

The rest of us don’t say anything, partly because we’re afraid the Sprout is taking notes and will fire us, but mostly because we are getting hungry and have lost the will to fight. Usually at these meetings there’s a stack of sandwiches and coffee—what the Sprout would call a carrot—and sometimes actual, literal carrots. But not today. Lizzie nudges Pru. The Sprout is in the corner, eyes narrowed in concentration, chin planted in chest. Jonah’s remarks have sent him deep into thought, so deep that he’s actually sleeping.

The outside world As we’re filing out, George, the lawyer, asks Maxine, Grab lunch?

Just like that.

Two words.

She beams at the prospect. Our jaws fall off their hinges and Crease mimes shooting himself in the head.

Lizzie goes foraging for Claritin and Red Bull. Does anyone want anything from the outside world? she asks.

On the way to the drugstore she spies George and Maxine sliding into his car, a silver BMW.

Maxine is gone for the rest of the day. We have all been monitoring the situation intently. Laars says something critical of BMWs, German engineering, the legal profession as a whole. Laars rides his bike to work when he can. Today he wears a faded long-sleeved T advertising a New Jersey swimming pool company, the white letters nearly washed away, a recent flea market find. What could Maxine possibly see in George? Pru points out that George wears a clean shirt, the kind with buttons.

Us/them Is Maxine one of us? One of them? For the first few months we were under the misapprehension that she was someone’s secretary, but then we started getting memos from her, some with a distinctly shape-up/ship-out undercurrent.

She might even outrank the Sprout. The subject merits closer, more fanatical observation. Could it be that the Sprout reports to her?

Pru tells us how all of the Sprout’s issues about working for such a practically mythological creature as Maxine get inflicted on us. His lust for her leads to his hatred of us, roughly. His fear of her makes him want us to fear him.

As Pru talks, she flowcharts it on a pad, little multidirectional arrows and FEAR in huge letters.

The cc game Against the advisement of George, Maxine will sometimes compliment us on our hair or other aspects of our scruffy appearance. The next day, or even later the same day, she’ll send an all-caps e-mail asking why a certain form is not on her desk. This will prompt a peppy reply, one barely stifling a howl of fear:

Hey Maxine!

The document you want was actually put in your in-box yesterday around lunchtime. I also e-mailed it to you and Russell. Let me know if you can’t find it!

Thanks!

Laars

P.S. I’m also attaching it again as a Word doc, just in case.

There’s so much wrong here: the fake-vague around lunchtime, the nonsensical Thanks, the quasi-casual postscript. The exclamation points look downright psychotic. Laars plays what he calls the cc game, sending the e-mail to the Sprout as well. You should always rope in an outside witness in order to prove your competence or innocence. On the other hand, this could be seen as whining.

Maxine never writes back. The Sprout will not get around to Laars’s e-mail for a week. He doesn’t like to deal with the petty stuff, though it could also be argued that he doesn’t like to deal with the big stuff, either.

He will study the e-mail for a few seconds, frown, and then delete it.

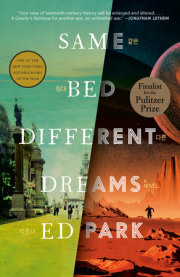

Copyright © 2008 by Ed Park. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.