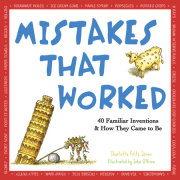

Some people leave their fingerprints in the cake frosting.

Other people’s names are on the menu.

Beef Stroganoff

The Stroganoff family was well known in Russia for hundreds of years. With their great wealth, they helped develop the Russian mining, fur, and timber industries. One of the last prominent members of the family was the popular Count Paul Stroganoff. In the early 1800s he was a diplomat, a member of the court of Tsar Alexander III, and a member of the Imperial Academy

of Arts.

He was also a gourmet who loved to entertain guests by hosting dinner parties. One of the dishes he often served was made with sautéed beef, onions, mushrooms, sour cream, and other condiments. This dish became known as beef Stroganoff.

Doesn’t it seem odd that a family who contributed so much to a great country’s development is remembered today for a beef dish served over noodles?

Caesar Salad

Caesar salad has

nothing to do with the emperor who ruled Rome two thousand years ago.

The Caesar salad at your local café was originally called aviator salad.

In 1924 an American named Alex Cardini worked at his brother’s restaurant in Tijuana, Mexico. One night, more customers than normal came in to eat, and the restaurant kitchen ran out of the usual menu items. So Alex put together odds and ends—eggs, romaine lettuce, Parmesan cheese, garlic, olive oil, lemon juice, and pepper. He made croutons out of some dried bread and then mixed everything together.

The customers loved it!

He named it aviator salad since the restaurant was near an airfield. Later the name was changed to Caesar salad after Alex’s brother, who owned the restaurant.

Eggs Benedict You won’t find eggs Benedict on a fast-food menu. It’s a very rich breakfast item made of English muffins, poached eggs, Canadian bacon, and hollandaise sauce.

There are two stories about the origin of eggs Benedict. Either might be true.

The first story: A wealthy lady named Mrs. LeGrand Benedict was having lunch at Delmonico’s, a restaurant in New York City, one Saturday in the 1920s. She complained that there was “nothing new” on the menu.

The chef put together “something new.” Mrs. Benedict was pleased, so the chef named it eggs Benedict.

The second story: Samuel Benedict, a New York socialite, had had too much to drink one night in 1894. He went into the Waldorf-Astoria the next morning and ordered his “perfect remedy for a hangover.” It was such a great combination that the hotel’s restaurant added it to the menu and named it eggs Benedict.

Graham Crackers

Sylvester Graham was a Presbyterian minister in Connecticut in the early 1800s. He was convinced that people were suffering from many bad habits, including poor diets.

He preached against tight clothing, soft mattresses, and alcohol. He thought pepper, mustard, and catsup caused insanity. He preached in favor of exercise, open bedroom windows, cold showers, and a vegetarian diet. He also recommended “cheerfulness at meals.”

Graham is probably most remembered for his belief that white bread was evil and people should eat “un- bolted” wheat flour (wheat flour from which the bran has not been removed). He urged women to stop buying bread from bakeries and instead to make their own.

This suggestion so infuriated professional bakers that a street fight once broke out in Boston after one of Graham’s sermons.

But Graham had many followers. Graham societies formed, and Graham boardinghouses and Graham food stores opened.

Today health experts know that Sylvester Graham wasn’t all wrong. People are exercising more, eating more vegetables, and using whole-wheat flour.

The graham cracker is still popular, although most commercial graham crackers are made with bleached flour, sugar, and preservatives—not the healthy ingredients the Reverend Sylvester

Copyright © 2018 by Charlotte Foltz Jones; illustrated by John O'Brien. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.