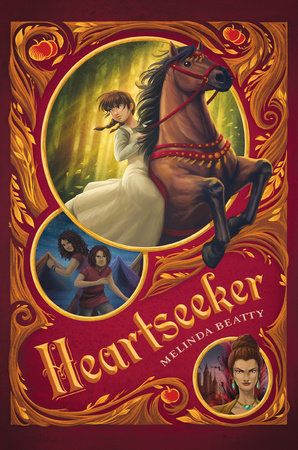

HEARTSEEKER

by Melinda Beatty

CHAPTER 1 Call out,call out, you loud jays, you honey-throated sparrows! Sing out the summer as it pours into the valleys, Into the Hush, the Rill, the Lannock, and the Blue. Cry warmth for the Sandkin plains, For the Mollier vines. Lift up your voices for gentle Dorvan tides And cool Folque stone. You sons and daughters ofOrstral, Join the chorus of the coming of the long light! -Jylla Burris, poet,

Songs of Orstral Lies are beautiful.

But when we're small, "You mustn't lie" is near the first thing we're taught. I didn't understand Mama's and Papa's serious faces when they finger-wagged my brothers and said that lying about wrongdoing was even worse than doing the wrong itself.

But then, no stern looks ever passed my way on the subject—of lies, that is. I knew from little that lies carried their own punishment and their own reward. Mama could always count on me to answer questions like, "Who tracked in all this mud?" or "Who broke the leg off the best dinner chair?" It wasn't that I wanted to tell her, but the truth always seemed to pour out before I could even think about fudging the story. Besides, saying anything other than the truth always ended with a dull thump behind my eyes. Not everyone could gasp like I could over the twinkling sparks or the colors that ringed bright halos round the liar, making the lie itself prettier than a summer sunset over the orchard. But I'd have given it all up in order to be able to tell one of my own.

I wasn't sure it was natural. The rector at sanctuary had always made plain his thoughts about unnaturalness. "Mother All sees you," he'd intone from the lectern, "and knows your heart. Seek out those things that are contrary to Her laws and push them far from you, lest you be corrupted by them." I knew well enough what corruption was. It was a blemish on the apple the brown, mushy blight under the skin that spreads, making the fruit fit for nothing. So I kept my secret close, buried under my own skin, like the seeds at the apple's heart. But as my non says, "Seeds ain't ever content to stay seeds. Seeds grow roots to take what they need from the dirt so they can see the sunlight."

When I'd just about seen seven harvests, Jonquin came in from the orchard bruised, bloody, and covered in earth and the stink of rotten fruit. Mama was at the stove, apron still wrapped round the brown day dress that she wore at the bakery. My brother's entrance surprised her so much that she dropped the ladle into the soup. It was usually Ether who could be counted upon to wander in covered in Mother knows what. But Jon—the Jon me and Ether got told we needed to be more like-wasn't one to come to dinner in such a state.

"What in the name of All happened to you?"

"Was climbing," he muttered, swallowing his words as if they'd had a bitter taste. "Fell out of Grandfather."

Ether was warned half a hundred times before breakfast not to venture too high into the tallest tree in the orchard, but long-legged Jon, who was thirteen and sure-footed as a squirrel, wouldn't be so clumsy. I couldn't help wondering what he was hiding with his eyes cast straight down to the floor.

A lapis-blue shimmer rippled around him, like the haze of a hot summer's day across an empty field. Ether told whoppers so often, he shone like a blacksmith's forge. He hadn't even got any shame left about it. But Jon did. And, oh, wasn't it lovely? I was so taken, I laughed out loud, dropping the pea pod I was shucking back into the basket between my knees. "Tell us another, Jon!"

Both my mother's and brother's head turned sharpish at me. They didn't half look alike, framed by the same ashen hair and peering with the same blue-gray eyes, though Mama's face was beset with puzzlement while Jon's was near murderous. I bit my tongue inside my mouth, trying to punish it for flapping when it should have been still. I wished I could've shrunk down to the size of a pea and dropped right into my own basket.

Mama gave him the hard eye, and her hands bunched on her hips in two tight circles. "Jonquin Fallow, have you been toward the kitchen window, revealing several fist-sized bruises on his cheek."I'd expect this sort of nonsense from your brother, not you!"

Jon opened his mouth as if he was going to deny the whole thing, then thought better of it.

"It won't happen again," he growled, wiping a smear of bloody dirt from the corner of his mouth. Blue flared out from behind him, daring me to look.

"Who was it?" Mama pressed.

Jon pressed his lips together, firm and thin, but his stubborn was no match for Mama's. "Lutha and Mandrake Bonniway," he answered at last.

"Those nasty whelps ain't no concern of yours. You go letting your pride get bigger than your sense, and a beating'll be the least of your worries." Mama picked a few bits of twig from his unruly hair, her face gentler now. "You're better than that, Jon."

My brother's face screwed up, and he cast his eyes at the floor, wrestling with shame.

Mama's nose wrinkled. "Ach, you smell like the bottom of the cider press. Go clean yourself up for dinner. We'll speak on this later."

Jon's shoulders, too narrow to be a man's but too broad to be a boy's, slumped in relief at having been dismissed to the wash room. The washroom was new-a spoil of our recent fortune.

It was only a bit of good luck that the Bird in'th Hand tavern

four barrels back with him, and, not three months later, returned with a royal warrant to supply the palace. Pasture that had been wild last season was now mown and either lined with new apple tree cuttings or purple with new lavender, which gave the Scrump its color and flavor.

But with the new coin came new troubles.

Having water that came into the house was a blessing to our backs, which got bent hauling bucket after bucket in from the well, but it didn't do much to wash away the envy of our halls mates. Presston was a simple place with simple folk-we all got on pretty much the same. When the warrant came, Mama and Papa urgently schooled us on modesty about our recent wealth. They knew what was coming, though it was a nasty surprise for me, Ether, and Jon. We never spoke a word about the washroom, the feather beds, or the clothes that weren't threadbare anymore, but we didn't have to. Everyone in town already knew.

For Jon and Ether, it was nothing short of a joy to have a wealth of fawning new friends. But, unlucky for me, I could see through the compliments not meant, the invitations given just 'cause of our coin. I began to prefer my own company to the false fondness of my hallsmates. They thought me proud or vain, but small as I was, being avoided felt better than lied to.

Then came the whispers that weren't really meant to be quiet. The shoves in the play yard that were harder than they needed be. It all told me one thing-they thought I was too big for my britches.

I snuck a peek at Mama, who was looking toward the washroom. I wondered if maybe I could make an escape and dodge any uncomfortable questions, but all too quick, she turned her eye on me. I froze like a rabbit faced with a hound.

"And you, little miss," she said sternly. "If you come across your brother tussling with those boys in the orchard again, expect to be told straightaway, are we clear?"

She thinks I saw it, I realized. "Yes'm," I said quickly.

She turned back to the stove, muttering her frustrations under the bubbling of the pots. I slid from my chair, put the basket on the floor, and crept into the stone room with its giant copper basins. Jon stood with his back to me, waiting for one to fill, but already he was hard at work, scrubbing his ears with a wet cloth. Blood from a cut on his temple clotted in his sandy hair. "Go away, Only."

I sat on the wooden stool that Papa had made so I could reach the washing basin. From there, I could see the bruise darkening on one of his cheekbones. "What'd Lutha and Drake do this time?"

A hard look came over my brother's dirty face. "They think they can just steal from us like it's nothing, but they'd never have done it before King Alphonse and his warrant. Lutha said we have fruit to spare now that we're rich."

"We ain't rich!" I exclaimed. The words were familiar-it felt like I didn't go one day at halls without someone raising my dan der with a taunt of "cat that got the cream" or "jinglepockets."

Jon didn't look at me as he held the cool cloth to the bruise. "Well, you know that I know that, but all anyone else knows is that Father makes Scrump for the king now, so we must be. And that means we got ideas above our station."

I thought for a moment. "Why did you lie to Mama? About falling out of Grandfather?"

"And that's another thing," he hissed, moving closer to my face. "Why would you fink me out like that? Where were you hiding? Up a tree?"

My heart sank. I never could bear his displeasure-not my Jon. If I couldn't tell

him, who

could I tell? "I wasn't there, Jon, honest. It was just so ... pretty."

"What do you mean, 'pretty'? What was pretty?"

"The lie you told. I could see it. Like a shimmer of blue, all round you."

His face twisted in confusion. "Only, you can't

see a lie."

"But I did, I

did see it!" I protested. "Tell another one and

I'll prove it!"

"Don't be stupid," Jon grumbled, stripping off his dirty tunic. "Just leave me alone so I can wash."

Mama was right. The rotted fruit flesh that was starting to dry on his clothes smelled to high All. "If you didn't fall out of Grandfather, how . . . ?"

"They pelted me with rotten apples from the ground after I lost the fight." My brother hung his head. "Just get out, all right?" Tears stinging my eyes, I slunk out the door feeling mad

for Jon, who didn't deserve to be abused by the neighborhood boys, as well as

at him for not believing me.

Peeved, I stomped out of the washroom only to run straight into Non.

Non's steady hands had brought me into the world and showed me the working of it. They taught me how to hold a knife, a spoon, and an apple peeler. They soothed my skinned knees and other small hurts with balms she made from the herb garden.

Everyone in town knew that Non was the one to go to for wisdom that'd bring peace to a troubled mind or an upset stomach. There was scarcely a soul in town that hadn't had some help from her healing hands-hands that now gripped my shoulders while her twinkling, crinkled eyes fixed on me like she'd never seen me before.

"It's a bad habit, mind," she began, her voice hushed, "but I couldn't help but sneak a listen at what you were jawing about with our Jon."

I crossed my arms in a temper. "Jon was just trying to stick up for the orchard. Those Bonniways deserved anything they got."

"Psht," Non snorted, waving her hand. "Boys'll always use their fists when they ought to use their words instead. What interests me more," she said, bringing her wrinkled face close to mine, "is what you had to say about lies."

Non shuffled me through the kitchen and toward the stable door that led to the garden. Mama turned her head as we passed. "Mam, where are you going with Only? I aim to put food on the table soon."

"Won't take but a minute, lovey," Non replied, giving my mother a gentle smile. '"Tain't nothing important, just pulling rosemary to go with the stew."

The same blue shimmer that had covered Jon shot faintly around Non, but her soft eyes turned to me, sharp and gray with warning. I heard my mother's voice exclaiming, "I've got plenty rosemary, Mam!" as Non hurried me out into the twilight.

The air was heavy with the scent of damp good earth and late-summer lavender. The faint sound of a fiddle drifted up the hill, along with bits of laughter and song. It was the first year Papa was to have the help of the Ordish with the harvest, and my heart was powerful curious. I'd seen the river folk's barges pass by before, but it was another thing to have them just at the bot tom of the hill with all their strange ways and little magics that could fool the eye or move the elements.

Non twigged the shine in my eyes. "Sounds lively, don't it? They're good folk, the Ordish. And they're hard workers, too."

"Papa says we're not to go near," I groused. There's nothing like being told not to do a thing to make you want to do it some thing fierce, but neither me, Ether, nor Jon wanted to be the whelp to have to clean the mash from the presses at the end of the season as part of our correction.

"And you must mind your papa," Non declared. "It takes a while to know the hearts of strangers. But I reckon we'll find them nowt too different from ours." She chucked me under the chin. "And it's matters of the heart we come out here to jaw on." We walked toward the small plot a little ways from the house where she grew her herbs. I knew well enough never to pluck anything from the soil without Non watching, as not every

thing there was friendly. Black currant grew next to nightberry, mint next to snakewort, and summer lemon next to daggeroot. It wouldn't take much to make a terrible, sickening mistake.

Non took a deep breath of the fragrant air as she sat on the stone bench beside the laurel bush and patted the empty space beside her.

"You know, Pip," she said after a moment, "you know that you're a good girl, don't you?"

I nodded. "Yes, Non."

She yanked a small sprig of rosemary and crushed it between her fingers. The savory smell made me think of the thick, delicious stew on the stove. My stomach grumbled, and I couldn't help but wonder why were we out here instead of sitting round the table.

"Your papa built that," she said finally, pointing at the handsome stone wall.

"I remember, Non. It was just this spring."

She chuckled and tapped the side of her head. "You think old Non's had a funny turn, I reckon, but I know what I'm about. What I'm trying to tell you is that lies are a bit like walls." Non pointed to the end of the garden. "What's on the other side of that one?"

Surely even Non wasn't so forgetful. "The lavender fields," I answered , puzzled.

"Good girl. How do you know?" I folded my arms. "I just

know!"

"Ah, but if you

didn't know, how could you tell?"

I jumped off the bench and marched over to the wall. Jamming my feet into the uneven stones, I climbed to the top. The fields of sweet purple blossoms stretched down to the edge of the river in the distance. "I can

see, Non!"

My grandmother rose slowly from the bench and joined me by the side of the wall, lifted me down, and covered my eyes with her hands. "What if you couldn't see over the wall? How would you know then?"

"Non!"

She took her hands from my eyes and grasped my shoulders. "Child, you mind me, do you hear? I've heard more odd complaints from folk over the years than you can imagine. Usually more'n once. But one thing I've never heard of is someone who can do what you said you could do, so I need you to answer me."

I never knew there was such a thing as something Non didn't know. What did that make me?

I shouldn't have opened my mouth to Jon! A few fearful tears spilled down my cheeks, but Non wiped them away with her thumbs. "See here, no tears, no tears, Pip.

You're a Fallow of the orchard. You're as tough as a green apple in summer. Now, once again, if you didn't know what was on the other side of the wall, how could you go about finding out?"

For a moment, I thought and breathed deep, trying to put aside the worry in my heart. Then it came to me.

"I can smell the lavender!"

I looked at Non eagerly, hoping for praise at my cleverness. She was smiling, but there was a sadness in it. Though I was heavy, she picked me up and rested me on her hip. We stared out over the darkening fields together.

"A lie," she began quietly, "is just a wall round the truth. Could be that it's built strong like your papa's wall, or it could be built out of something that'll collapse the minute you shake it. But no matter what it's made of, the truth is

always going to want to get out, whether it has to climb over, break through, or leak out the cracks."

"What does that mean, Non?"

She didn't meet my eye, but her lined face looked more serious than I'd ever seen it. "The Ordish have got their auguries. Some can work the wind in the sails or the water beneath their keels. I heard tell of some who can even read the heavens, but those things ain't too common among landwalkers. You hear stories sometimes, down south where there's been more folk that marry into river clans or out of 'em. There'll be a whelp come up that can do some little magics-glamours and the like. Nothin' of particular use. But you ... " She trailed off, her eyebrows making a worried V on her forehead.

Just the mention of magics put the fear of All up my spine. It never occurred to me that my little talent might be an augury. The words made me think terrible thoughts. Would Mama and Papa put me out of the house if they found out? Would my brothers hate me? Would I even be allowed to attend halls if someone found out my secret?

The cry of the fiddle drifted into the garden again, clear as a night heron.

"Mam! Only! Come to table!"

Non started at Mama's voice from the house. She looked at me as if she'd forgotten I was there and smiled a sad smile. "Psht! Look at us, mooning over the fields like a couple of daydreamers when there's a good stew on the go. Come on, you heard your mam."

"But, Non ... "

Non held up her finger. "We'll have no more tonight. Let me sit with it for a while. But let's keep this between us for now, eh?"

She stood and offered me her hand to make our way back to the house, which looked warm and welcoming with light spilling out the windows. The halo it made round her stirred something in me.

"Ain't we forgetting something, Non?"

She cocked her head, puzzled. "What's that, Pip?" "Rosemary."

Non chuckled. "I plum near forgot." She stooped to tear a few sprigs from the earth and put a warm arm round my shoulders.

"You'll keep me right, Pip. You'll keep me right."

Copyright © 2018 by Melinda Beatty. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.