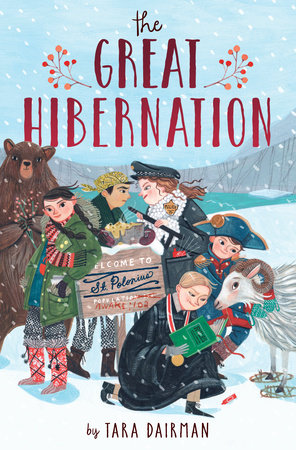

Chapter 1

The bear was dead.

Or was supposed to be by now, anyway. The eight-year-old boy in the bear suit still danced across the stage, roaring and clutching his stomach. “ARRRR!”

In the audience, Jean Huddy stifled a laugh. She looked up at her brother, Micah, onstage in his seventeenth-century-seafarer costume. He was trying not to laugh, too.

Micah was playing Captain Polonius--the hero of The Founders’ Story--but everyone knew that the best role was the bear. When Jean was in third grade, it had gone to her best friend, Katrin Ash. Katrin had transformed herself into a wild animal, but now Micah’s own best friend, Axel Gorson, was giving her performance a run for its money.

“AIEEEE!” With one final spin, Axel collapsed at Micah’s feet. The audience cheered. Micah knelt, pulled a sponge soaked in red thistleberry juice out of a hidden pocket in the bear suit, and held the fake “liver” high up over his head. He then tore it into pieces and passed it out among his classmates, who were playing shipwrecked sailors. They pretended to gobble the liver down, chorusing “Yum!” and smiling.

The audience cheered louder, but Jean didn’t join in. She knew what was coming after the play. On Founders’ Day, the citizens of St. Polonius-on-the-Fjord really did eat a bite of bear liver--but no one said “Yum!” Bear liver smelled like a wet dog and, from what Jean had heard, tasted even worse. Every resident who was at least twelve years, four months, and six days old (as this had been the age of the youngest sailor on Captain Polonius’s original crew) was required to take part in the ritual . . . and today, Jean was twelve years, four months, and nineteen days old.

It’s an honor to participate--her parents had been saying this all week. Unfortunately, Jean wasn’t too good at bringing honor to her family. At the school-wide spelling bee, she’d been the first student eliminated; even Micah, four years younger than she was, had lasted a few rounds. And back when she was Micah’s age in The Founders’ Story, she’d bungled her only line in front of the entire town.

This year that line belonged to Cora Buggins, a tiny seven-year-old who carried a purple stuffed narwhal everywhere she went. She had even snuck it up onstage under her sailor’s coat--Jean could see its horn poking out of Cora’s sleeve.

“Great saints, but I am sleepy!” the girl cried. Her voice squeaked, but at least the words made sense. Jean cringed at the memory of her own version (“Great slaints, but I am seepy!”), and the laughter that had followed.

All the little sailors onstage slumped forward and pretended to fall asleep.

The Founders’ Story was an odd tale. Jean had no trouble believing that, in 1674, Captain Polonius and his crew had shipwrecked on this barren northern peninsula and started to starve as winter set in. And it made sense that Polonius would pray to the saints to use their ancient powers to save his crew. But why, of all things, would the saints send a bear staggering down from the mountains as a source of food? Couldn’t they have simply washed fish up on the shore, or made the thistleberry bushes fruit early?

And then why, after Polonius had slain the bear, did his crew eat only its liver?

And, most importantly, how did the crew then manage to sleep through the entire winter without eating, drinking, or even taking shelter from the elements? Now the third graders were rubbing their eyes, pretending to wake up months later in the spring.

Jean knew the official answer.

“It’s a miracle!” cried the little sailors. They declared Captain Polonius a saint for bringing about their miraculous hibernation, and named their settlement for him. Then Micah, standing tall at center stage, declared: “Every year hence, you townsfolk will honor the founding of St. Polonius-on-the-Fjord by slaying a bear and feasting on its liver! If you don’t, you’ll bring the wrath of the saints on yourselves.”

Next to her, Jean’s mom rolled her eyes.

That morning, over toast and sheep’s-milk yogurt, Mom had given Micah an earful. “Dad and I are so proud of you for winning the lead role. But don’t take the story too seriously! If you ask me, it’s a canoe full of codwash. Saintly magic and miracles--more like superstition and nonsense.”

“Now, now,” their dad had said, his thick eyebrows waggling as he reached for the smoked herring. “I wouldn’t be so quick to dismiss the story. In my research, I’ve learned that even the tallest tales can hold a grain of truth.”

Dad taught history at the town’s small university extension, specializing in the sagas of the North Country. But he also loved to joke around. Jean couldn’t tell if he was serious or not.

Micah looked as confused as Jean felt. “Mom . . . if you don’t believe in the old stories, then why do you always eat the liver?”

Mom sighed. “It’s complicated, kiddo. Traditions . . . they’re still important. When your people have been doing something for generations, you don’t throw that all away at once.”

Jean thought about that as Micah and his class took their bows. Her parents ate the liver every year, and the fact that she was about to join them did mean something.

Dad reached over and squeezed Jean’s hand. “You ready?” Jean nodded as volunteers began to swarm the aisles, carrying big silver bowls.

The musty odor of the liver hit her nose. She knew the smell well from past Founders’ Days, and her guts twisted. For a desperate moment, she considered pulling the sleeve of her coat over the red bracelet she’d been given upon entering the tent, the one that meant she was of age. But she was sitting between her parents. Even if no one else saw her dodge the liver-tasting, they would.

Holding her breath as a silver bowl paused in front of her, she took a wooden spoon with its shiny scoop of meat.

It’s just a sliver, she told herself. A sliver of liver. A giggle escaped her lips, and the old woman in front of her turned and frowned.

Mayor King climbed up onstage, his sallow face framed by a magnificent bear-fur collar. The audience fell silent. Jean could hear the arctic wind howling outside, but the tent was hot from the press of bodies in winter coats.

At the mayor’s signal, everyone rose from their seats. “In the name of the Sailors,” he intoned, “the Saints, and the Miraculous Bear!”

“In the name of the Sailors, the Saints, and the Miraculous Bear!” the crowd repeated, and then, as one, they raised their spoons to their lips. An honor to participate, Jean reminded herself, and maybe curses from the saints if I don’t.

She shoved her liver as far back into her mouth as she could. If she didn’t chew it, maybe she wouldn’t taste it! She swallowed the bite down whole . . . and started to gag. The stuff shot back up: bitter, sour, even sickly sweet.

Stomach heaving, Jean tore out of the tent. Frigid air whipped her dark hair off her face as the liver-sliver splatted out onto a snowdrift. Her knees buckled, and she had to grab one of the tent poles to keep herself upright.

A shadow fell across the snow at her feet. Jean turned to find two familiar sets of eyes upon her.

She dropped her gaze, unable to withstand her parents’ looks of surprise. St. Polonians were the descendants of great seafarers. If they weren’t born with iron stomachs, they were at least supposed to have developed them by age twelve.

Jean shuffled sideways, but it was too late to hide her mess. She had faced her first test as a full-grown citizen of St. Polonius-on-the-Fjord--and she had failed.

“Are you all right?” Dad asked.

Jean nodded but couldn’t meet his eyes. Every snowflake that fell on her head made her tremble harder. The Tasting of the Sacred Bear Liver was in the town charter. Any citizen who didn’t complete it had to be reported to the authorities. No one had failed to eat their portion in years, but everyone knew the traditional punishment: being marooned on a slab of ice in the North Sea. Jean didn’t know for how long, but it had to be long enough to appease the saints; it was long enough for one citizen in the 1800s to have lost four toes and an earlobe.

She sucked in a breath, the frosty air stinging her raw throat. “I’ll turn myself in. I’ll go see Mayor King.”

Mom stepped forward. She was hatless, her short black hairs freezing into tiny, spiky icicles. “You’ll do no such thing.” She stomped her heavy work boot into the snowdrift and kicked a pile of loose snow into the hole she had created.

Just like that, all evidence of Jean’s sickness was erased. “You’ll do nothing,” Mom continued in a hushed tone, “because nothing happened. Right, Brian?”

“Right,” Dad said.

Jean was flabbergasted. “But the charter--”

“Curse that infernal charter!” Mom was angry-whispering now. “This town is far too obsessed with saintly nonsense. If you could see some of the other ridiculous laws that are still on the books . . .”

Dad put a calming hand on Mom’s shoulder. She often got worked up about politics.

“I think Jean had the right idea today,” Dad said in a lighter tone. “This year’s liver tasted especially disgusting. I strongly considered throwing it up myself!”

In spite of everything, a tiny smile crossed Jean’s lips.

“Still . . .” He eyed the tent flap. “I don’t think anyone else in town needs to know about this.”

“No,” Mom said. “They don’t. Jean, you’ll say nothing to anyone. You promise?”

A burst of applause sounded from the tent, and Jean nodded quickly as people began to emerge. The very first person out was Magnus King, son of the mayor. Though he was Jean’s classmate, they rarely spoke--which was why she was surprised when he hurried over.

“Jean!” he cried. “Are you unwell? I saw you run out of the tasting.”

“Busybody,” Jean’s mom muttered as Magnus skidded to a stop in the snow in front of them. He was panting, and his gold spelling-bee medal bobbed up and down on his chest. He never went anywhere without that medal. Katrin called him “Magnus the Magnificent,” and she didn’t mean it as a compliment.

“Jean is fine,” Mom said before Jean could open her mouth. “She just got a little overheated in there, right, honey?”

“Right,” Jean said. The tent had been hot.

“I have to go find your brother,” Mom said to Jean, “but why don’t you and Dad get a drink?”

“That’s a great idea,” Dad said. “Come on, Jean--we’ll get some thistleberry tea to wash that nasty liver taste out of our mouths!”

Magnus looked scandalized. “Excuse me, Professor Huddy,” he said, “but some of us take the Tasting of the Sacred Bear Liver very seriously. If I had been of age to take part this year, I surely wouldn’t be complaining about the taste.”

Jean believed him. Magnus had missed being old enough to participate in this year’s tasting by only three weeks, and he’d been grumping about it for ages.

“Well, good for you,” Dad said. “Now, if you’ll excuse me and my daughter . . .”

“I’ll join you!” Magnus said heartily. “A cup of thistleberry tea sounds like just the thing to quaff in this weather. Q-U-A-F-F--it means ‘to drink.’ ” Since he’d won the bee, Magnus was constantly spelling and defining words.

“And then,” he continued, “we can all head to town hall for my father’s Founders’ Day address.”

The mayor’s address! Jean sighed, though she tried to direct her breath away from Magnus, sure it still smelled like liver-vomit. Mayor King was known for his endless, droning speeches. And considering that he was running for reelection and had a proposal up for a vote next week, his speech tonight was likely to be longer than most.

Magnus fell into step beside Jean and her dad--no escaping him now.

Festival activities were resuming around the square: Brass instruments echoed from the band shell, and children shrieked as they chased each other, waving toy harpoons they’d won at a game booth. Food carts switched on their lamps as the weak arctic sun sank over the fjord-waters. Jean looked around for Katrin but couldn’t find her in the crowd.

Dad steered them to the thistleberry tea cart, and Magnus stepped right up. “Three mugs,” he said to the vendor. “For me and the Huddys--my treat.”

The vendor frowned slightly, and Jean didn’t blame him. “My treat,” coming from a King, really meant it would be the vendor’s treat, since the mayor’s family was never actually made to pay for anything in St. Polonius. She turned to Dad to protest, but he had fallen into conversation with Pastor Thornhill in line behind them.

“Would you get a load of that?” Magnus said as he passed Jean a mug. “The Ratanas are here.” Their classmate Isara Ratana and his parents were leaving the performance tent. Like Jean, Isara wore a red bracelet that meant he was old enough to taste the Sacred Bear Liver.

The Ratanas had moved to town the year before, all the way from Thailand. Isara’s parents had opened a restaurant called the Tasty Thai Hut that Jean had never tried but Katrin said was good. Isara was fairly quiet at school. When he did speak, he had a bit of an accent, but he had mastered their language speedily; in fact, he had long outlasted Jean in the spelling bee.

“Why wouldn’t they be here?” Jean asked.

“Well . . . because they aren’t from here.” Magnus spoke slowly, like he was back at the bee, spelling out a complicated word for the judges. “Founders’ Day is for St. Polonians, to celebrate our history.”

Jean didn’t like what he was getting at. “There are plenty of people who live in this town but aren’t from here,” she said. “Like Katrin’s mom . . . and my dad’s neighbor at the university, Dr. Fields. No one complains about them participating.”

“That’s different,” Magnus said. “Dr. Fields is from Bigsby, right on the other side of the fjord. And Katrin’s mom moved here decades ago. The Ratanas haven’t even been here a year!”

Jean took a swig of her thistleberry tea, letting its warm sweet-and-sourness roll around her mouth. She was pretty sure the real reason Magnus didn’t like the Ratanas was that before they’d arrived, he’d been the best soccer player on the primary school’s team. Now Isara was the champ.

Magnus rubbed his medal against his coat, ridding it of snowflakes. “We’d better head inside,” he said, “if we want to nab good spots for my father’s address. It was my idea to hold it in town hall this year--so everyone can listen comfortably to the entire speech, protected from the elements.”

Copyright © 2017 by Tara Dairman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.