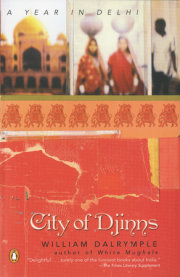

Chapter One: A Chessboard King The marriage procession of Prince Jawan Bakht left the Lahore Gate of the Red Fort at 2 a.m. on the hot summer night of 2 April 1852.

With a salute from the cannon stationed on the ramparts, and an arc of fireworks and rockets fired aloft from the illuminated turrets of the Fort, the two gates opposite the great thoroughfare of Chandni Chowk swung open.

The first to emerge were the

chobdars, or mace bearers. The people of Delhi have never much liked being restrained by barriers and were in the habit of breaking through the bamboo railings hung with lamps that illuminated the processional route. It was the job of the

chobdars to clear a way through the excitable crowd, before the imperial elephants—always a little unpredictable in the presence of fireworks—appeared lumbering through the gates.

Two ministers of state on horseback began the procession proper. Shell ornaments were plaited into the horses’ manes, and bells strung around their necks and fetlocks, and as they rode out, the ministers were attended by servants with

punkahs (fans). Then came a troop of Mughal infantry, with polished black shields and curved swords, long lances and fluttering pennons of green and gold.

The first six of the imperial elephants followed, caparisoned with gold and saffron headcloths embroidered with the Emperor’s coat of arms. From the howdahs, officials held aloft the dynastic insignia that had been used by the Mughals since their arrival in India more than three centuries earlier: from one, the face of a rayed sun; from another, two golden fish suspended at each end of a golden bow; from the third, the head of a lion-like beast; from the fourth, a golden Hand of Fatima; from the fifth, a horse’s head; and from the last, a

chatri, or imperial umbrella. All were made of gold and were raised on gilt staffs from which trailed silken streamers.

There then emerged in turn a party of red-tunicked Palace servants carrying covered trays of food and gifts for the bride’s family; a squadron of camels, with drums beating and guns firing in the air; a small regiment of British sepoys led by Captain Douglas, Commandant of the Palace Guards, all in tight-fitting busbees and blue-and-saffron uniforms, and escorting two light cannon; a troop of Skinner’s Horse in their yellow tunics and scarlet sashes, topped by armoured breastplates and medieval-looking helmets; a group of bullock-drawn wagons on which sat several bands of Mughal kettle drummers,

shanai players, trumpeters and cymbal clashers; and a European brougham carriage, painted kingfisher blue, containing a party of senior princes, their gilt brocade flashing in the light of the exploding fireworks.

After each group came parties of torchbearers, holding their flames aloft, interspersed with men holding candles in glass bell jars. There were also gangs of water carriers emptying their skins onto the road in an attempt to settle the billowing summer dust kicked up by the procession.

After the brougham there came a second, smaller group of younger princes, this time riding on horseback; and among them, in the very centre, rode the groom. Mirza Jawan Bakht was only eleven years old, a young bridegroom even in a society that tended to marry its offspring early in adolesence. Immediately behind the Prince swayed the elephant on which rode the Emperor himself, sitting in his golden howdah and decked out, despite the sweltering night heat, in his state robes and jewels, and attended by his personal bearer holding a peacock fan. The rest of the court followed behind on foot, a great snaking queue stretching back through Chatta Chowk, the Fort bazaar, to the Naqqar Khana Darwaza, or the Gate of the Drum House, in the very centre of the Fort.

Not long before this, the Emperor and Jawan Bakht had both sat for the Austrian artist August Schoefft. The portrait of Zafar depicts a dignified, reserved and rather beautiful old man with a fine aquiline nose and a carefully trimmed beard. Despite his height and surprisingly broad and muscular build, there is a profound gentleness and sensitivity in his large brown watery eyes with their unusually long lashes. As a teenage prince, Zafar had always appeared in his portraits as a slightly awkward and uncertain figure, plump, visibly ill at ease and thinly bearded. But as youth gave way to middle age he had grown into his looks, and in old age—unusually—looked finer than ever. Now in his mid-seventies, his cheeks were sallow, his nose more pronounced and his bearing more regal. Yet as the elderly monarch kneels, wearily fingering his beads, there remains in the expression of his dark eyes something unmistakably melancholic; in the set of his full lips there is still that air of sad, patient resignation visible in the earlier pictures. Schoefft shows Zafar a little swamped under the brocade cloth of gold which adorns him, somewhat weighed down by the huge blood-coloured rubies and the strings of vast pearls, each the size of a partridge egg, which seem to hang so heavily around his neck. It is a portrait of a man imprisoned by the trappings of his office.

By contrast, the young Jawan Bakht, the Emperor’s favourite son, seems to relish all the pearls and gems, the jewelled daggers and inlaid swords with which he is bedecked with a lavishness almost equal to that of his father. His expression is different too: knowingly handsome, and oddly cocky and confident for a boy of eleven. He is as strikingly sure of himself as his father appears wearily uncertain.

One person missing from both the portraits and the wedding procession was the woman who had done more than anything else to bring the marriage about. For months, Zafar’s favourite wife, Zinat Mahal, had been preparing for this day. In Mughal tradition, women did not accompany the

barat taking the groom to his marriage—not even mothers and queens; but every detail of the procession had been planned by her. For Mirza Jawan Bakht was Zinat Mahal’s only son, and her one ambition, to which she held consistently throughout her life, was to see Jawan Bakht, Zafar’s fifteenth son, placed on the throne at the death of his father.

The exceptionally lavish wedding she had planned was intended by her to raise the profile of the Prince, and also to consolidate her own place in the dynasty: Jawan Bakht’s bride, the Nawab Shah Zamani Begum, who was probably no more than ten years old at the time of the wedding, was Zinat’s niece, and her father, Walidad Khan of Malagarh, an important ally of the Queen. While so young a couple would not be expected to consummate their marriage for a year or two, or even to live together, political considerations meant that the marriage should go ahead immediately, without having to wait for the couple to reach puberty.

As conceived by Zinat, the wedding of Mirza Jawan Bakht was of a scale unparalleled in Delhi in living memory, eclipsing the weddings of all Jawan Bakht’s elder brothers. Sixty years later, the young courtier Zahir Dehlavi, whose job it was to oversee the care of the

Mahi Maraatib, or Fish Standard, still remembered the aroma of the trays of food from the royal kitchens that had been sent out to every Palace official, and the spectacular entertainments that preceded the main celebration: “Such beauty and magnificence had never been seen before,” he wrote many years later, in exile in Hyderabad. “At least not in my lifetime. It was a celebration I shall never forget.”

The festivities had begun three days before the marriage with a procession from the house of Walidad Khan to the Palace, bearing the principal wedding gifts, followed by fireworks: “a brilliant train of elephants, camels, horses and conveyances of every denomination,” according to the

Delhi Gazette. This led on to the ceremony of the

mehndi, when the hands of the couple and their guests, including all the women of the Palace, were decorated with henna; the celebrations would continue for a further seven days beyond the night of the wedding ceremony.

On the evening of the great procession, at the beginning of the night vigil known as the

ratjaga, Zafar had bestowed on Jawan Bakht a wedding veil made of strings of pearls known as a

sehra, and simultaneous parties of escalating grandeur had been arranged for the different ranks of the Palace, each with their own musicians and troupes of dancing girls. Selected townspeople were in one courtyard, Palace children and students in another, senior officials in a third, and the princes in a fourth.

Since Zafar’s financial resources rarely matched his spending, let alone that of his wife, much of the initial work for the wedding had involved arranging loans from Delhi moneylenders, who knew from experience what the chances were of seeing their cash again. Since December, the British Resident’s diary of court proceedings had been full of Zinat’s attempts to procure the large amounts needed, something she achieved in the end with the aid of the notoriously ruthless Chief Eunuch of the Palace, Mahbub Ali Khan. The Palace was repaired, spring-cleaned and superbly decorated with lamps and chandeliers. Getting sufficiently magnificent fireworks was another major concern, with pyrotechnicians from across Hindustan summoned to the Palace throughout January and February to demonstrate their skills.

The rockets, squibs and Roman candles were still exploding around the great red sandstone curtain walls of the Fort as the wedding procession slowly proceeded westwards down the top of Chandni Chowk, with its trees and central canal glittering in the light of the torches. It snaked onwards, past the gardens of Begum Sumru’s haveli, recently taken over by the new Delhi Bank, and through the Dariba—now in the light of ten thousand candles and lanterns haloed in dust—before veering left and heading under the latticed windows of the courtesans’

kothis (town houses) lining the Kucha Bulaqi Begum.

On the procession passed, turning again under the moonlit white marble domes of the Jama Masjid. It then looped down the Khas Bazaar, before skirting the much smaller but beautifully gilt and illuminated domes of the Suneheri Masjid, and on through the Faiz Bazaar into Daryaganj. Here lay the city’s great aristocratic palaces, such as the famous

kothi of the Nawab of Jhajjar, which, according to Bishop Heber, the Anglican Primate of Calcutta, “far exceed in grandeur anything seen in Moscow.” Among them lay the procession’s destination, the haveli of Walidad Khan.

On the way, as the Palace diary puts it, “His Majesty’s officers presented their

nazrs [ceremonial gifts] as the procession passed their several dwellings, while HM inspected the illuminations on the road.” The conspicuously wealthy streets through which the procession passed were still very much a Mughal creation. In 1852, despite 150 years of decline and political reversals, Delhi was once again the largest pre-colonial city in India—a position it had recently regained from Lucknow—and as the

Dar ul-Mulk, the seat of the Mughal, was the epitome of an elegant Mughal metropolis: “In this beautiful city,” wrote the poet Mir, “the streets are not mere streets, they are like the album of a painter.” A similar idea was conveyed by another Delhi writer of the period, who compared the waters of the canals of Delhi’s gardens to the burnished border on an illuminated manuscript page: “its waters, like mercury, a

jadval [margin] of pure silver running over a page of stone.”

At the same time as the ruling houses of Murshidabad and Lucknow were experimenting with Western fashions and Western classical architecture, Delhi remained firmly, and proudly, a centre of Mughal style. There was no question of Zafar turning up in durbar (court) dressed as a British admiral or even a vicar of the Church of England, as had been heard of in the Nawab’s court in Lucknow. Nor was there much trace of Western architectural influence in the buildings erected by the later Mughal emperors: Zafar’s new gateway at his summer palace, Zafar Mahal, and his delicate floating garden pavilion in Mehtab Bagh, the scented night garden of the Red Fort, were both built in the full Mughal style of Shah Jahan.

What was true of the court was true of the city: with the single exception of the Delhi Bank—formerly the great Palladian Palace of the Begum Sumru—the buildings that the marriage procession passed showed little experimentation with Western classical pediments or square Georgian windows, though such attempts at synthesis had long been common in Lucknow, and in Jaipur. In 1852, British additions within the walls of Delhi were limited to a domed church, a classical Residency building recently converted into the Delhi College, and a strongly fortified magazine, all of which stood to the north of the Fort and out of sight of the path of the procession. Moreover, there were still relatively few Europeans in Delhi—probably well under a hundred within the walls: as the poet and literary critic Azad later put it, “those were the days when if a European was seen in Delhi, people considered him an extraordinary sample of God’s handiwork, and pointed him out to each other: ‘Look, there goes a European!’”

Others, it was true, took a less charitable view. So prevalent was the belief among Delhiwallahs that Englishmen were the product of an illicit union between apes and the women of Sri Lanka (or alternatively between “apes and hogs”) that the city’s leading theologian, Shah Abdul Aziz, had to issue a fatwa expressing his opinion that such a view had no basis in the Koran or the Hadiths, and that however oddly the

firangis might behave, they were none the less Christians and thus People of the Book. As long as wine and pork were not served, it was therefore perfectly permissible to mix with them (if one should for any strange reason wish to do so) and even, on occasion, to share their food.

Partly as a result of this lack of regular contact with Europeans, Delhi remained a profoundly self-confident place, quite at ease with its own brilliance and the superiority of its

tahzib, its cultured and polished urbanity. It was a city that had yet to suffer the collapse of self-belief that inevitably comes with the onset of open and unbridled colonialism. Instead, Delhi was still in many ways a bubble of conservative Mughal traditionalism in an already fast-changing India. When someone in Shahjahanabad wished to praise another citizen of the city, he would still reach for the ancient yardsticks of medieval Islamic rhetoric, cloaked in time-worn poetic tropes: the women of Delhi were as tall and slender as cypresses; the Delhi men as generous as Feridun, as learned as Plato, as wise as Solomon; their physicans were as skilled as Galen. One man who was quite clear about the virtues of his home city and its inhabitants was the young Sayyid Ahmad Khan: “The water of Delhi is sweet to the taste, the air is excellent, and there are hardly any diseases,” he wrote.

"By God’s grace the inhabitants are fair and good looking, and in their youth uniquely attractive. Nobody from any other city can measure up to them . . . In particular the men of the city are interested in learning and in cultivating the arts, spending their days and nights reading and writing. If each of their traits were recounted it would amount to a treatise on good conduct."

Copyright © 2007 by William Dalrymple. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.