ONE Monster Business Most kids clear out of the way when I walk down the hall. They’re like campers in a forest who spot a grizzly and scramble up a tree to hide. (Or, in this case, climb into a locker.) I’ve been called the Mastodon of Montgomery Middle, the Springfield Skyscraper, the Moving Mountain, the Terrible Tower, the . . . You get the idea.

These names bothered me in sixth grade when I was excited to start middle school and make friends. But now, in eighth grade, my size has become a profit center. And business is booming.

Take these two kids sitting down in the back corner of the library (my office), fidgeting like I’m going to eat them or something. One has practically chewed off his fingernails, and the other one’s leg won’t stop bouncing.

I hear them whispering.

“What?” I say.

“Is it true?” the kid asks. “That you carried forty two chairs to the auditorium? By yourself?”

I stare. “Yes.”

Actually it was only eight chairs, but these are the kinds of rumors that are good for business.

“Incredible.”

They start whispering to each other again.

“We’re wondering if we could procure your walking services, Mr. Marcus?”

“Don’t call me that.”

At the start of the school year, a bunch of sixth graders confused me for a teacher while they were trying to find the auditorium. I told them they’d better figure out where they needed to go or I was going to collect a tax from them for getting in the way. They ran. Soon a rumor started spreading that I was really an undercover assistant principal hired to keep kids in line. It’s kind of ridiculous, but things at Montgomery often are.

The rumors about me have gone from fantastical (Godzilla with a crew cut) to realistic (assistant principal). It’s really annoying. But like I said, I’ve found a way to make it work for me. These two kids are here for my walking service, the crown jewel of my business.

“Five bucks a week to walk each of you to school,” I say. “And five bucks to get you home. Your total invoice is ten per week.”

“Each of us?” The kid seems surprised.

“I could walk you halfway for half the price.”

They look at each other a moment.

“That’s my blue-plate special,” I say.

“No, we’ll take the whole service. Thank you.”

“Where do you live?”

“I live on Maple and Vine,” one kid says.

The other kid chimes in with, “I’m on Vine and North Cherry Hill Drive.”

I already walk four other kids who live in the Cherry Hill neighborhood, so two more isn’t a big deal. I can’t charge them more than ten bucks, or parents will start to wonder. The way I see it, it’s a win-win for everyone. I’m making some money, and these kids are getting protection from bullying on their walks to and from school. I’m doing a service. People pay for bodyguards all the time. That’s what I am to these kids—a big, bad bodyguard.

“Hey,” I tell them before they run off to class.

“There’s a deposit. Five bucks each.”

I always take a deposit for my services. It’s like insurance money. They both pull out fives and hand them to me. Then they quickly get out of my office.

Most of my business transactions happen in the small cubicle located behind a shelf at the far end of the library. The school librarian lets me hang there whenever I want. I usually take a stack of books to read while I wait for my “clients.” In exchange for the office space, I help the librarian shelve books.

I carefully fold the cash into my pocket and pull out my business spiral from my backpack to write down the names of my new clients. I check my cell phone storage tab before I close it. I need to pick up the slack on that. I’ve only collected two cell phones today. That’s just three bucks.

Here at Montgomery, there is zero cell phone use during school hours. Kids were getting their phones stolen and/or thrown into the lunchtime garbage can by older kids. (Trust me, you don’t want your cell phone tossed in there. I don’t even put my own garbage in there.) Besides all of that, Principal Jenkins said students were “spending too much time texting and using social media.”

Some parents cheered Principal Jenkins’s decision. Others, not so much. In the end, a compromise was made. Kids could have a phone in their lockers but were not permitted to carry them around, and they definitely could not have them in class.

Around mid-September, two seventh graders bumped into me because they were texting each other while walking to class. They tried to apologize, but I saw an opportunity. I decided to take their phones and charge them a “storage fee” until school got out. I let them come to my locker, send a text or two, then return the phones until they left school. I’ve collected phones one hundred and twenty-seven times since school started. That’s almost two hundred bucks.

I look at another tab in my portfolio.

garbage tax collection (year two)

week 25 = $2

Business is way down. I started collecting a garbage tax last year when kids kept dumping stuff on the floor, leaving empty soda cans in the library or crumpled paper in classrooms. It became so bad, Principal Jenkins said he would give detention to any student caught littering on school grounds. That’s how the garbage tax was born.

The idea came to me when I was sitting in my office and I heard a couple of kids chatting. I stood and peeked over the shelves to find a boy and girl had sneaked two sodas into the library. They finished, left the cans on a shelf, and took a few books to the circulation desk.

I walked over, grabbed the evidence, and waited for them outside.

The girl was surprised to see me standing there. She stepped back and tried to smile. “Hi,” she said.

I showed them the cans. “Know what this means?”

I asked.

The girl looked worried. “Please don’t tell,” she said.

“My parents will kill me if I get detention.”

“We can pay you!” the boy blurted out.

“How much?” I said.

“Um . . .” The boy looked at the girl.

“Twenty-five cents,” the girl offered.

“Fifty,” I said.

They looked at each other again.

“Fifty cents to save our butts from detention?”

“How do we know you won’t tell?” the girl asked.

“Because I would have already told if I didn’t think there was something I could get out of it.”

“Fair enough,” the girl said. “Here you go.” She shook my hand and gave me a dollar. “For me and my friend.”

I took the money and threw the cans into the recycling bin. I wrote in my spiral the date I collected the tax, the reason for collecting it, and how much I got for it. After that, I started watching for litterbugs. Most kids wanted to avoid detention, so to them, fifty cents was an even trade for my silence.

Recently, business has really dropped off. Hardly any kids leave trash behind now. Principal Jenkins thinks his policy is what turned the school around. The threat of detention was one reason. Paying my tax to avoid getting caught was a bigger one.

I do some stuff for free, too. (Cuz, you know, I’m not a monster.) I carry equipment to school rallies and assemblies, I move desks for teachers, and I help out the maintenance staff with stuff like moving bleachers or rolling out the big garbage bins on trash day. I like the maintenance people. They treat me like a normal kid just helping out.

But I guess I’m not a normal kid. I was born eleven pounds, twenty-six inches. Doesn’t seem big until you consider that most babies are more like seven or eight pounds and nineteen or twenty inches when they’re born. You get the idea. I was a big infant. Ninety-seventh-percentile big.

While most kids just stare, the only kid who never misses a chance to tell me I’m not normal is Stephen Hobert.

Stephen pronounces his name like he’s French, but his family is from Springfield and I know for a fact he’s never been to France. His mom is the head of the parents’ association. She doesn’t like students who stand out for “all the wrong reasons.”

Stephen has a crew. I’ve seen them pick on kids. Sixth graders are especially afraid of him (in a different way than they are afraid of me). They don’t want to get on his bad side.

He draws pictures of people he doesn’t like and sneaks them into their backpacks and lockers. I caught him once putting one of his masterpieces inside a girl’s backpack. At lunch later that day the girl was crying with her friends as she showed them the drawing. I happened to see it as I walked to a lunch table. Stephen drew her like a stick figure with a big round head, bulging eyes, short hair, and a tie. Above the drawing, he wrote, “Is it a boy or a girl?”

Stephen uses words like someone throwing punches.

Only it’s nearly impossible to find the bruises. He’s never been caught.

I don’t collect garbage tax or cell phone storage fees from Stephen. I’ve thought long and hard about it. Sure, he had made a monster out of me by spreading rumors and just being his terrible self. But in a way, he’s responsible for my biggest source of income—keeping kids away from him.

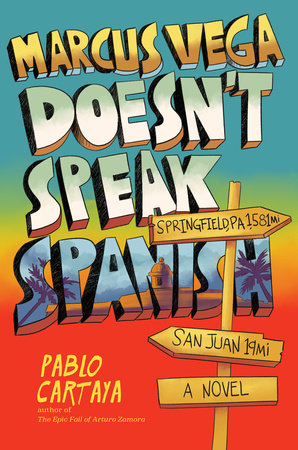

Copyright © 2018 by Pablo Cartaya. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.