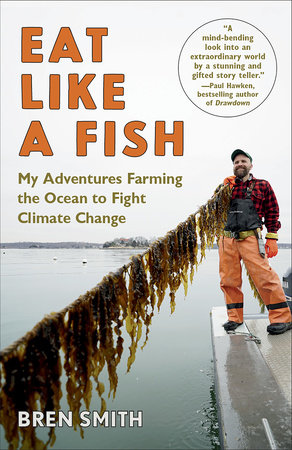

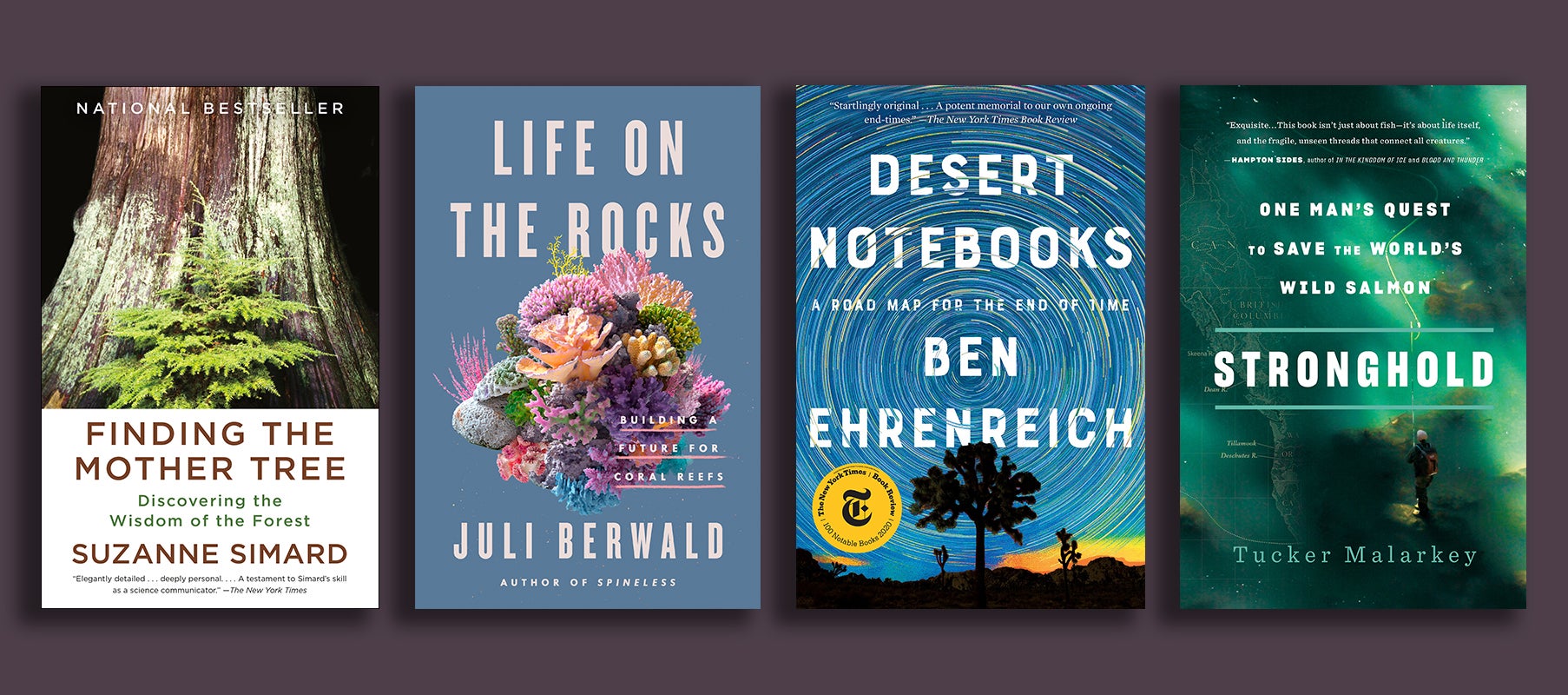

I am a restorative ocean farmer. It’s a trade both old and new, a job rooted in thousands of years of history, dating back to Roman times. I used to be a commercial fisherman, chasing your dinner on the high seas for a living, but now I farm twenty acres of saltwater, growing a mix of sea greens and shellfish.

I’ve paid my debt to the sea. I dropped out of high school to fish and spent too many nights in jail. My body is beat to hell: I crawl out of bed like a lobster most mornings. I’ve lost vision in half my right eye from a chemical splash in Alaska. I’m an epileptic who can’t swim, and I’m allergic to shellfish.

But every shiver of pain has been worth it. It’s a meaningful life. I’m proud to spend my days helping feed my community, and if all goes well, I will die on my boat one day. Maybe get a small obit in the town paper, letting friends know that I was taken by the ocean, that I died a proud farmer growing food underwater. That I wasn’t a tree hugger but spent my days listening to and learning from waves and weather. That I believed in building a world where we can all make a living on a living planet.

Fishermen must tell our own stories. Normally, you hear from us through the thrill-seeking writer, a Melville or Hemingway, trolling my culture for tall tales, or a Greenpeace exposé written from the high perch of environmentalism, or the foodie’s fetishization of artisanal hook and line. When fishermen don’t tell our own stories, the salt and stink of the ocean are lost: how the high seas destroy our bodies but lift our hearts, how anger and violence spawn solidarity and love. There’s more edge to fishermen—more swearing, more fights, more drugs—and we are both victims and stewards of the sea.

So this is my story. It’s been a long, blustery journey to get here, but as I look back over my shoulder, a tale of ecological redemption emerges from the fog. It begins with a high school dropout pillaging the high seas for McDonald’s and ends with a quiet ocean farmer growing sea greens and shellfish in the “urban sea” of Long Island Sound. It’s a story of a Newfoundland kid forged by violence, adrenaline, and the thrill of the hunt. It’s about the humility of being in forty-foot seas, the pride of being in the belly of a boat with thirteen others working thirty-hour shifts. About a farm destroyed by two hurricanes and reborn through blue-collar innovation. It is a story of fear and love for our changing seas.

But, most important, it’s a search for a meaningful and self-directed life, one that honors the tradition of seafaring culture but brings a new approach to feeding the country among the wandering rocks of the climate crisis and inequality. As fishermen and farmers before me, all I’ve asked for is a job that fills my chest with pride, a working life that my people can write and sing songs about.

I still miss being a commercial fisherman. But that’s over now. Overfishing, climate change, acidification have forced me to change course. Now I have more in common with a kale farmer than I do with fishermen. My life is quiet, constant—working the same patch of ocean day after day for over a decade. I can’t hang out in the same bars: What fish tales would I tell? Would I swagger into the Crow’s Nest, turn up the lilt of my Newfoundland accent, order a stout, and tell a yarn about seaweed? “There I was in fucking flat calm. Reached down with my gaff, hooked a buoy, and up came my kelp, glistening brown wide blades. Fifteen feet. Longest I’d seen it in years. Yes, b’y, it was something to see.”

I’d be laughed out of the bar.

About this book Writing this book was hard. My early years are fogged with drug-fueled violence and adrenaline, and I suspect drenched in over-the-shoulder romanticism. A life seen in reverse is an untidy affair. I struggled with structure. After much wrangling, I decided to weave together five concurrent strands.

First is my evolution from fisherman to ocean farmer. It was a difficult, emotional birth. I had to rewire my nervous system to new tempos of work, grow a blue thumb, hang out with odd breeds of people, even learn a new vernacular of food. It was a bumpy trip: my first brush with aquaculture left me disillusioned, and I’ve made many mistakes along the way to becoming a restorative famer, but in the end I landed on my feet.

The second strand is my rocky romance with sea greens. Like most Americans, I was skeptical about moving seaweed to the center of the dinner plate. Honestly, except for sushi, it sounded kind of gross. But I fell in love with a food lover, and she took me by the hand on a long journey of discovery. We met chefs specializing in making unappetizing food beautiful and delicious, learned about the lost culinary history of Western seaweed cuisine, and tested out kelp dishes on roofers and plumbers. In the book I’ve included a handful of recipes developed by Brooks Headley and David Santos, two of the most creative working chefs in the United States, whose work points the way toward a delicious future.

The third strand is instructional: how to start your own underwater garden. It provides the basics for building a farm, seeding kelp and shellfish, and provides tips on farm maintenance and harvesting. It’s not comprehensive, of course, but it might wet your whistle.

Fourth is my journey of learning. I had a long history of struggling in school, but yearned for a way to understand my life on the ocean within a larger context. So I trace my learning curve through the rise of industrial aquaculture and the origins of restorative ocean farming to the secret strategy to convince Americans to eat kale and the emergence of the regenerative economy. There were many surprises along the way. Who knew that the Japanese consider an Englishwoman the birthing mother of nori farming and hold a festival in her honor every year? Or that a shipwrecked Irishman accidentally invented mussel cultivation while trying to net some birds to eat? Or that McDonald’s pioneered a seaweed-based burger in the 1990s?

Finally, there is my tale of passing the baton. This didn’t always go well. I swam with the sharks of Wall Street, drowned in viral media, and failed at building a new processing company. But it was worth the trip, because out of the ashes came GreenWave, a training program for new farmers, partnerships with visionary companies like Patagonia in the era of climate change, and a new generation of ocean farmers to take over the helm and release me back to my beloved farm.

You’ll also hear a lot about kelp in the book. On my farm, we’ve experimented with a few different kinds of seaweed, but sugar kelp has emerged as the most productive, delicious, and viable native species in my area. Most of the book will refer to kelp, but know that, every day, farmers, scientists, and chefs around the world are figuring out new ways to grow and use the thousands of vegetables in the ocean.

Though I include a lot about kelp, I’ve written very little about Asian cuisine. The history of seaweed use in East Asia is well documented, and I could never do it justice. What’s surprising is the largely unknown parallel history—reaching back thousands of years—of shellfish and seaweed cultivation and cooking in the West. At times these two histories intersect, which I explore in the book, but I figured my job as a U.S.-based ocean farmer was to explore my own regional roots, and ways to cook and work with sea greens within the region I know.

Although I’m an ocean famer, I am not a fish farmer. The vast majority of aquaculture has entailed humans’ trying to grow animals that swim. Recently, there have been major advances in the industry, but my take—which routinely drops me into hot water with the fish-farming crowd—is that the United States chose the wrong path for ocean agriculture and continues to do so. Over the previous decades, there were countless opportunities to reflect on the unique qualities of the ocean from a farming perspective. If the nation had chosen to focus energies on growing restorative species such as seaweeds rather than jailing and feeding fish, we’d have a much more sensible dinner plate today. We’d be feeding the planet while breathing life back into our seas, and protecting wild fish stocks while creating middle-class jobs.

There will be gaps in my story. For example, I am estranged from most of my family, a history that I will address with silence. They are good people; I could have been a better man. And I’ve worked many different jobs in my life. I’ve driven lumber trucks and sold my wood carvings on the streets of New York City. I’ve worked on community-organizing campaigns with coal miners, immigrants, and fishermen, and even did a stint for a politician. But these have all been mere tributaries. Though I have been pushed off the water many times in my life, I have always fought to return. This is a tale of a fisherman’s forty-five-year search for meaningful work at sea. Maybe one day I’ll spin another yarn of my dizzy days on land, but for now I’ll stick mostly to the saltier side of my life.

A note about foul language. In his book

Distant Water: The Fate of the North Atlantic Fisherman, Pulitzer Prize–winning author William W. Warner tries to prepare his readers for the cultural shock to come:

The fishermen in some chapters swear more than others. No national slights are therefore intended. All fishermen have their choice epithets. . . . Their oaths and swear words are mere interstices—points of emphasis, like raising one’s voice—devoid of literal meaning. The reader should so understand them, and take no offence.

So, before we dive in, let me apologize in advance. I write about the slimy, violent end of things, especially in describing my early years. And I swear a fair amount, always have, which has remained a sore point even at home.

Convention says I should repent and prefer the sober, inoffensive, and violence-free life—but I don’t. The knife’s edge has been good to me. Making the world a better and more beautiful place isn’t about “softening” for the dinner crowd. It’s about the granular hard work of fighting waves and rolling up tattooed sleeves to work with nature. It’s not about “domestication,” it’s about blue-collar innovation. So leave civility on the docks; hop aboard and revel with me in the profane. It tastes so good.

A few words about word choice. While some prefer the term “fishers,” I use “fishermen” to refer to both men and women who fish commercially for a living. Many have come to this consensus. As Clare Leschin-Hoar, who has extensively covered the fishing industry, explains: “I’ve met many female fishermen . . . and 100 percent of the time, they have told me they like the term ‘fishermen’; they don’t want to be called fishers.” She says women in the fishing industry see the term as a badge of honor. “They worked very hard to become commercial fishermen, and they want that respect.” I follow their lead.

To refer to my farming model, I use “restorative ocean farming,” “regenerative ocean farming,” or “3D ocean farming.” This signals my search for a new lexicon for sea-based agriculture. I hate the term “aquaculture,” but honestly, I haven’t yet settled on what to call my type of farming. Same goes for seaweed, which I refer to as “sea greens,” “sea vegetables,” and “ocean greens.” In some of the more scientific sections, you might even see “macroalgae”—that just means seaweed, too. If you have better names, let me know; I’m keeping a list. Also, for all you landlubbers: at sea, rope is called “line.”

What is restorative ocean farming? Picture my farm as a vertical underwater garden: hurricane-proof anchors on the edges connected by horizontal ropes floating six feet below the surface. From these lines, kelp and other kinds of seaweed grow vertically downward, next to scallops in hanging nets that look like Japanese lanterns and mussels held in suspension in mesh socks. On the seafloor below sit oysters in cages, and then clams buried in the mud bottom.

My crops are restorative. Shellfish and seaweeds are powerful agents of renewal. A seaweed like kelp is called the “sequoia of the sea” because it absorbs five times more carbon than land-based plants and is heralded as the culinary equivalent of the electric car. Oysters and mussels filter up to fifty gallons of water a day, removing nitrogen, a nutrient that is the root cause of the ever-expanding dead zones in the ocean. And my farm functions as a storm-surge protector and an artificial reef, both helping to protect shoreline communities and attracting more than 150 species of aquatic life, which come to hide, eat, and thrive.

Shellfish and seaweed require zero inputs—no freshwater, no fertilizers, no feed. They simply grow by soaking up ocean nutrients, making it, hands down, the most sustainable form of food production on the planet.

My farm design is open-source and replicable: just an underwater rope scaffolding that’s cheap and easy to build. All you need is $20,000, twenty acres, and a boat. And it churns out a lot of food: up to 150,000 shellfish and ten tons of seaweed per acre. Because it is low-cost to build, it can be replicated quickly. Best of all, you can make a living: one farm can net up to $90,000 to $120,000 per year.

Finally, the model is scalable. There are more than ten thousand plants in the ocean, and hundreds of varieties of shellfish. We eat only a few kinds, and we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface of what we can grow. Imagine being a chef and discovering that there are thousands of vegetable species you’ve never cooked with or tasted before. It’s like discovering corn, arugula, tomatoes, and lettuce for the first time. Moreover, demand for our crops is not dependent solely on food; our seaweeds can be used as fertilizers, animal feeds, even zero-input biofuels.

As ocean farmers, we can simultaneously create jobs, feed the planet, and fight climate change. According to the World Bank, a network of ocean farms equivalent to 5 percent of U.S. territorial waters can have a deep impact with a small footprint, creating fifty million direct jobs, producing protein equivalent to 2.3 trillion hamburgers, and sequestering carbon equal to the output of twenty million cars. Another study found that a network of farms totaling the size of Washington State could supply enough protein for every person living today. And farming 9 percent of the world’s oceans could generate enough biofuel to replace all current fossil-fuel energy.

Copyright © 2019 by Bren Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.