Chapter OneFinding the Lost Mary

Who are my mother and my brothers and my sisters?

—Jesus

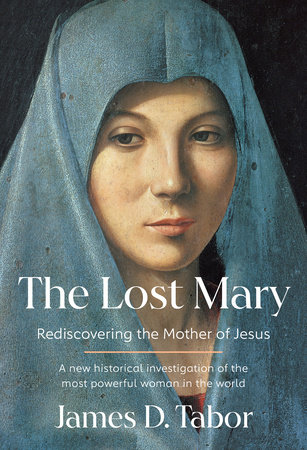

Jesus’s mother, Mary, is the best-known, least-known woman in history. Recognized and revered by countless millions, at the same time she is almost wholly forgotten. I am thinking here of the historical Mary, the

real Mary, a remarkable woman in her own time who has largely been lost to us through the thick fog of later tradition and theology.

I have spent the past two decades investigating this remarkable paradox. Towering over the ancient city of Jerusalem, just north of the Old City walls, is the Vatican’s Notre Dame of Jerusalem Center. “Notre Dame” means “Our Lady” in French, referring of course to the Virgin Mary. Pope Francis stayed there on his historic visit to the Holy Land in 2014. The main building has two elaborate towers with a taller center pedestal, atop which sits a statue of a young Mary holding up her child, Jesus. She is visible from anywhere in the area, overlooking the Old City that faces the Mount of Olives to the east. I often ask my students, newly arrived in Jerusalem, “Why is there a statue of that Jewish girl, holding her Jewish baby, on top of the Roman Catholic Notre Dame Center?”

It takes them a moment to get the irony. Who thinks of Mary as Jewish? For most of us she is the quintessential image of a pious Catholic, very much a nun or sister in clothing and demeanor. And that seems to be our indelible cultural image of Mary, reinforced by statues, paintings, and films. Hail Mary, Mother of God, Queen of Heaven.

Mary is the most “erased” woman in history. I believe this transformation was deliberate, and as a result, finding the “real” Mary is no easy task. I am a historian of ancient Mediterranean religions, with a focus on ancient Judaism and early Christianity. I have written books on Jesus and Paul, but by far my search for Mary has been the great challenge of my career. This book is the result. I hope it will inform, surprise, and inspire readers to remember Mary as she was in her own time and place—the creative, revolutionary Jewish Matriarch of the early Christian faith.

That Mary is the most notable of all women who have ever lived is indisputable. Helen of Troy, Cleopatra, Joan of Arc, and Queen Elizabeth fade into comparative obscurity next to Mary. Mary’s entry in

Wikipedia runs thirty pages, more than that of any other woman. The great museums of Western culture, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, to the Prado in Madrid or the Louvre in Paris, feature more representations of Mary than of any other person, whether paintings, drawings, frescoes, or sculptures, not to mention the innumerable holy cards, pictures, and images in countless homes, shops, public spaces, and churches. I should add that Mary is surely the most famous woman in Jewish history as well, even though, given her makeover by the Catholic Church, that fact is largely unrecognized by Jews as well as by Christians—and certainly not within our global culture.

Two and a half billion Christians plus a billion and a half Muslims—nearly half the world’s population—honor her memory. Millions of Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians hail her with the direct invocation of the Rosary: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.” Although Protestants don’t pray to Mary, they remember her as the Holy and Blessed Virgin, God’s chosen “vessel” to bring Jesus, the divine Son of God, into the world.

Mary, or Maryam in Arabic, is the only woman named in the Qur’an, and she has a substantial sura, or chapter, devoted to her story. The Qur’an lists Mary among the prophets; she is addressed as a “messenger” and receives more attention than the half-dozen or so other women mentioned but not named. Muslims believe she is the virgin mother of Jesus, “who guarded her private part,” as God breathed into her some of his Spirit, generating her pregnancy (21:91).

And yet if we ask about the

Jewish woman behind the images, icons, portraits, and dogmas—the real Mary, in her own time and place—little has survived, whether in popular imagination or in theological formulations.

People remember Mary as the young virgin mother of Jesus in the Christmas story who then suddenly reappears at Jesus’s crucifixion. What is missing here is Mary’s

entire life.

Where did she grow up? Do we know anything about her father and mother— or any siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins in her extended family? Why do we suddenly find her pregnant and living in Nazareth in our earliest account—was that her hometown (Luke 1:26–31)? Our first account of Jesus as an adult is when he is nearly thirty years old— so what about Mary during those “missing” thirty years? There is evidence she might have lost her husband, Joseph, and ended up a widow during that period. If she had other children, do we know anything about them—how many, their names, any traditions about them? How was the family supported? Can we say anything about her daily life— as a Jewish woman of her time? Did she or his family ever travel with Jesus when he was out preaching after he went public at age thirty? Would she have encouraged him in his aspirations? Was she worried about the dangers that could result in making any kind of messianic claims or his proclamation that the “kingdom of God” was at hand, as he joined the John the Baptizer? According to the Hebrew prophets this meant a total upturn of society—politically, socially, religiously, and culturally.

And perhaps most important, when we hear the voice of Jesus—“Do good even to those who wrong you,” “Don’t judge by outward appearances,” or “Become a servant in order to be great”—are we not hearing the voice of Mary, like any good mother, imparting to her children the principles of life and behavior from an earliest age? This book lays out the case that Jesus did not suddenly invent himself the day he was baptized by John the Baptizer and went public. He had thirty years of growing up in a large family, working in the building trades, and filling in as the eldest son in supporting Mary and assisting her in guiding the family. And so much more. Mary was not just a vessel who brought Jesus into the world; she was a proud Jewish woman with a

life of years of devoted motherhood and guidance.

Our New Testament evidence, by some measures, could be considered sparse. She appears only a dozen or so times in our New Testament Gospels and once in the book of Acts. This rather strange omission seems hardly by chance. There is evidence that it was based on theology rather than history, and there is a good argument to be made that the downplaying of the importance of the “earthly” family of Jesus—beyond his birth—was intentional. Paul visited Jerusalem several times in the forties and fifties AD, and he mentions women often by name in his letters—but never Mary. In fact, his remark that Jesus was “born of a woman” in Galatians 4:4 seems particularly odd, since in the same letter he writes of meeting “James the Lord’s brother,” and staying with Peter as a guest for fifteen days on one of his visits to Jerusalem (Galatians 1:18–19). The letters attributed to Peter and John, who, according to Paul, also lived in Jerusalem and shared leadership with James, are equally silent about Mary.

However, each scene in the Gospels is rich with interpretive possibilities, hidden clues strewn along an uncharted path. Taken together and put into their historical contexts, we can lift the veil on the human Mary and catch unexpected glimpses that shatter our preconceptions and assumptions.

I have been tracking these fleeting shadowy glimpses of Mary for the past twenty years. I’ve done sleuthing in libraries, digging at archaeological sites, and walking the hills, valleys, and pathways Mary once trod. (I have made more than seventy trips to the Holy Land over the past three decades.) In addition to carefully reexamining New Testament materials, I have pored over important Jewish sources and newly discovered texts that have surfaced just in the past hundred years. These manuscripts and textual sources are undoubtedly exciting, but some of my most enlightening discoveries about Mary have come literally from the ground—the results of recent archaeological excavations in the Holy Land, including some in which I have been involved. From the piles of books, files, and manuscripts that surround me in my office to explorations in the ancient land of Israel, my quest has uncovered surprising revelations. Often what is not said can reveal unexpected insights, and many times a seemingly minor detail can open a whole vista of new understanding.

I have taught Christian Origins for the past four decades at the University of Notre Dame, the College of William and Mary, and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I could not count the times over the years when I have mentioned the four brothers and three sisters of Jesus who are named in our ancient sources, only to have a student raise a hand and say, “I had no idea that Jesus even had brothers and sisters!” My guess is that many reading this book are in the same position. This confusion about Mary and her family is understandable, since the Roman Catholic Church insists these children were cousins, whereas the Eastern Orthodox maintain they were children of her much older husband, Joseph, from a previous marriage. Neither view is found in the New Testament. The truth is, Mary herself, along with her other children, has been intentionally removed from many of our sources. As a result, our culture has inherited a mythical and legendary Mary shaped by two millennia of theology and church dogma.

I present evidence that Mary is one of the forgotten founders of earliest Christianity—very much the godmother of the Jesus movement— in contrast to the mother of God in the Christian creeds. She apparently ended up a widow sometime before Jesus reached adulthood, as the last reference we have to her husband, Joseph, in any of our sources is one text when Jesus is twelve years old (Luke 2:41–51). Several gospel texts describe Jesus as the eldest son, head of the family. As a single parent, Mary raised her eight children under Roman military occupation through one of the bloodiest and most brutal periods of Roman history.

What I call Mary’s “doubly royal” status is one of the key factors in recovering our lost Mary. She was of Davidic lineage—descended from the bloodline of King David— a royal pedigree passed on to her children. Accordingly, any of her sons was a potential candidate for the messianic throne. The prophet Isaiah had predicted that before the end of the age a descendant of David, widely spoken of as the Messiah, would usher in justice and peace throughout the entire world (Isaiah 11:1–9). But what is not widely recognized is that Mary stems from a distinguished priestly pedigree as well. In the Western Christian tradition this has been almost wholly forgotten. Fortunately, the evidence for her priestly ancestry survives, in a half-dozen texts, primarily preserved in Eastern sources, that have been either overlooked or marginalized.

Whatever we attribute to Jesus and the remarkable movement he inspired, Mary’s vital role as the matriarch of this large Jewish family was central, both before and after the death of Jesus. Few are aware that it was her second-born son, James, with Mary by his side, who took over the leadership of the movement after Jesus’s execution. The succession was dynastic, based on Mary’s royal and priestly lineage. And when James was brutally stoned and beaten to death in AD 62, by the Jewish high priest Annas, his aged brother Simon assumed his place of leadership, only to be crucified under the emperor Trajan.

The ways in which Mary was gradually sidelined and written out of the story in our New Testament gospels reflects the political and theological struggles that took place among later Christian theologians who were anxious to strip her of any kind of sexuality. They also presented Peter and Paul as the coleaders of the Jesus movement, effectively writing Mary’s son James out of the picture. Fortunately, we have reliable sources, in both the New Testament and shortly thereafter, that preserve an alternative narrative that fully acknowledges James as the successor of Jesus and leader of his apostles and other followers.

Christian theology, very early on, molded Mary into a passive, nonsexual, apolitical woman. She was portrayed as a pious celibate, a retiring nunlike figure, largely removed from the main drama of the story. This theologically driven counternarrative began to gain ground in the generations after her lifetime and persists in our New Testament writings. The architects of this counternarrative sought to reshape the revolutionary political message that centered on the arrival of the kingdom of God on earth into one about escaping this world and finding salvation in heaven. It became important to deemphasize and even eliminate Jesus’s mortal family to focus on his exalted divinity and Mary’s new role as the glorified “Mother of God.” A complex mix of varied interests and forces contributed to this transformation. This desire to remove Mary from the earthly human realm to the divine heavenly sphere, while marginalizing her womanhood, motherhood, and Jewishness, was central to this theological agenda.

This book is an alternative contribution to “Marian devotions,” the term millions of Christian believers use to describe their faith in Mary as the Mother of God. It is an attempt to restore Mary to her fully human life as a Jewish mother of her time.

Some may feel this historical perspective diminishes Mary’s holiness or is even blasphemous, given the ideas of “perpetual virginity” that developed long after her death. I think the opposite is the case. Many believing Christians are fine with studies of the historical Jesus—including understanding him as a Jew— as a way of getting us closer to who he was in his own time. Even the idea of a married Jesus has been openly discussed and considered in our post–

Da Vinci Code world.

It is time to pursue a similar quest for Mary. Presenting the real Mary represents an important part of such devotion. Leading scholars and historians have pioneered just such a quest in recent years, stressing the vital leadership role of early Christianity’s marginalized and forgotten women. The silencing of women’s voices and the negation of their achievements is deeply embedded in our historical records, including within the New Testament itself. In Mary’s case, recovering her life as a Jewish woman and single widowed mother is long overdue. By righting the cultural record, we endeavor to return women—and mothers— to their rightful place in history.

In Bruce Barton’s 1925 bestseller on the life of Jesus,

The Man Nobody Knows, he tried to strip Jesus of his theological garb and present him as a man of his time. Mary is, beyond question, the Woman Nobody Knows. I believe the multiple millions who are drawn to Mary for spiritual reasons will welcome an attempt to give Mary her life back, coming to know her as she was in her own time, freed from later church dogmas, theological formulations, mythology, and legend. The excitement of this very possibility is as inspiring as it is potentially revolutionary.

Recovering the real Mary buried in the depths of history requires careful examination of all our sources, paying particular attention to the dating of surviving evidence, which turns out to be a key factor, since the erasure of Mary and her family was progressively advanced with time.

I identify the main stages of Mary’s displacement, the forces at work, and the underlying motivations, the outcomes and results, not only to shed light on what happened but to set the stage for a new era, one created for our own time: the fundamental possibility that we can resurrect the Lost Mary.

I write these words in my hotel room in Jerusalem, a ten-minute walk from Mount Zion, where Mary lived out the last decades of her life. To her and to all who honor her memory I dedicate this book:

Ave Maria.

The Sabbath Day, April 5, 2025

Christian Quarter, Old City Jerusalem

Copyright © 2025 by James D. Tabor. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.