Chapter One

The Garden Spot of Virginia

Leave the sprawl of the national metropolis behind and drive south into Virginia on the crowded superhighway that leads to Fredericksburg. Turn east, though, at Fredericksburg and follow the old King’s Highway, where the land stretches to the tree lines on either side, fragrant with hay and wheat and corn. There are few houses at the roadside, only occasional farm stands hawking fresh produce, and small horse farms with white fences reaching up to the road’s edge. Old names appear on gray historical wayside markers—Lamb’s Creek, King’s Charter—and the ground has the feel of a flatness that should roll away forever to the left or right.

This, of course, is a deception. As it moves east, the highway is actually bisecting a long, narrow peninsula, the Northern Neck of Virginia, a formidable, tall plateau with cliffs that fall down sharply either to the swan-shaped estuary of the Potomac River on the left or to the Rappahannock River on the right. In the War of 1812, British warships boldly stalked along the Potomac shore of the Northern Neck, landing parties of marines and sailors to burn farms and plantations; fifty years later, the Rappahannock shore was the line that for two years separated Union occupation from tenacious Confederate defense. After twenty miles, the four-lane passes out of King George County and enters Westmoreland County, and narrows to a two-lane road where spindly pine trees with enormous high crowns crowd down to the verge. The horse farms become more numerous, but the houses more weather-beaten and isolated. Fifteen miles farther, a marker points toward the Potomac and the birthplace of George Washington, and finally, five miles more, the trees suddenly fall back on either side, and a sharp turn at a pristine white clapboard Anglican church brings you, after a mile, to a gatehouse set amid “cedars, oaks and forest poplars.”

Slip past the gatehouse, under the dark, thick shade of hickory, tulip, and holly trees, and suddenly, emerging in the opening distance, is Stratford Hall, what Myron Magnet was moved to call “a fanfare in brick,” a proclamation of the superiority of design and intelligence over a building material not always noted for spectacular architectural statement. Wood had long been the principal building resource for the Neck. Brick moved Stratford far in advance of its peers. And such brick: hot-fired Flemish bond to give it sheen, laid in checkerboard style on the basement story, light-colored headers and stretchers alternating with the darker bricks. “There is, we presume, no structure like it in our country,” gushed a national newspaper in 1848. Three centuries ago, this was built to be the home of Thomas Lee, and it was in a very real sense Lee’s bid to be considered the greatest of the Lees of Virginia, and the Lees the greatest family of the Neck’s Potomac shoreline.

From thy south shore, great stream of swans,

Came the great Lees and Washingtons.1

But Stratford, like the Neck itself, is full of appearances that hard realities often belie. It was not Thomas Lee’s fortune that built Stratford so much as that of his wife, Hannah Ludwell. And the ninety-foot-long house is actually only a one-story affair, built over a spacious basement, its enormous row of sixteen-over-sixteen windows all around the house creating an illusion of grandeur and height, resembling in layout a very squat and exaggerated capital H. But the central hall is a magnificent showpiece, twenty-nine feet square with a seventeen-foot tray ceiling. Eight enormous chimneys, vaulting upward in two quadrangles like towers, shoulder the task of proclaiming the glory of the Lees, while fine brick “dependencies” stand watch at each corner, flanked by two formal gardens and a six-bay stable.2

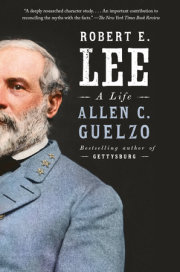

Thomas Lee died in 1750, only ten years after the house’s completion. It would remain in the hands of succeeding Lees for three brief, and increasingly incapable, generations, until 1822. What would make Stratford worth remembering, and in time worth preserving with the most startlingly meticulous care as an American shrine, was that on January 19, 1807, it became the birthplace of the one member of the family every Virginian would recognize more readily than any Virginia leader after Washington, an individual revered so steadfastly across the Old South that one artist, Clyde Broadway, could portray him as the third person in every Southerner’s historical version of a holy trinity—Robert Edward Lee.3

—

There is no way to pinpoint the arrival of the original Lee in Virginia apart from placing it generally in 1640. Richard Lee was probably the younger son of a family of Shropshire gentry who, with no fortune before him in England, turned his hand to finding one in the New World. This was not the most fortuitous moment for a gentleman’s son to swagger off to Virginia. The Virginia colony had been founded as a monopoly corporation, only to founder on the shoals of bad planning, decimating diseases, an Indian massacre, and an overall mortality rate approaching 65 percent of all its immigrants. King James I then assumed direct royal control of the colony and proceeded to appoint governors whom the Virginia settlers preferred to resist and occasionally overthrow.4

Richard Lee “was a man of good stature, comely visage, and enterprising genius, a sound head, vigorous spirit and generous nature,” and he would need all of those assets to survive in Virginia. “Ignorance, ingenuity, & covetousness” were the governing rules of Virginia life, and it seemed “the intencions of the people in Virginia” amounted to nothing beyond getting “a little wealth . . . and to return to Englande.” Not until the arrival of Sir William Berkeley in 1642 did a governor with a sufficiently hard hand force the fifteen thousand or so colonists into line. That lasted only until 1652, when civil war in England toppled King James’s successor, Charles I, and brought a well-armed fleet up the James River to send Berkeley into retirement. Not for long, though. The restoration of the monarchy in England in 1660 brought Berkeley back to his governorship and Virginia back to the service of the new king, Charles II, its “most potent mighty & undoubted king.”5

Through it all, Berkeley had no more loyal follower than Richard Lee, nor one more faithfully rewarded. By 1649, he had become Berkeley’s secretary of state and in 1651 joined the governor’s council. Political position gave him an advantage in acquiring wealth, which in Virginia meant land. So, even while the civil war in England was turning politics on both sides of the English Atlantic topsy-turvy, Lee shrewdly settled on the western tip of the Northern Neck, where he patented an estate on Dividing Creek and built the house that became known as Cobbs Hall. By the time he died in 1664, he had acquired sixteen thousand Virginia acres, more than half of them on the Northern Neck.6

There was, unhappily for Richard Lee, no opportunity in the midst of the English Civil War to confirm any of these dealings in England. In the years when Charles II had been forced to eke out a penurious life in French-supported exile, his only hope of fanning the embers of loyalty in his band of followers was the lavish pledges he made in the form of proprietary land grants in America. There was, however, no one at the right hand of the youthful exile to correct him when he awarded the entirety of the Northern Neck to seven of his most devoted followers.7

When, to the general surprise of Europe, Charles II was actually invited by a disheartened Parliament to reclaim his throne, the king’s proprietors found that entrepreneurs like Richard Lee had already claimed title to much of the Neck and were understandably resistant to conceding it. Nor could Lee in particular be dispossessed on the easy ground that he had been untrue to the monarchy. A series of unpleasant negotiations ensued between 1669 and 1680 that finally confirmed the Northern Neck as a proprietorship in the hands of Lord Thomas Culpeper, but with maddeningly generous exceptions for those who already claimed property there. When Culpeper died in 1689, the proprietorship passed into the hands of Culpeper’s relative by marriage Lord Thomas Fairfax, whereupon the haggling over who owned what on the Neck resumed, to the point where Fairfax heartily wished “we had neaver medeled with them.”8

The Lee family’s solution to this threat was to go to work for the Fairfax family. The first instinct of Richard Lee’s heirs had been to fight for his original titles. But Richard’s grandson Thomas Lee thought better of this. In 1713, when the Fairfax family grew dissatisfied with the revenues being passed to them through the hands of their existing agent, Robert “King” Carter, they turned to Thomas Lee, who served them, to the mutual satisfaction of both Lees and Fairfaxes, until 1747.9

As his reward, Thomas Lee built a comfortable gentleman’s country seat (and land office) on Machodoc Creek, which he named Mount Pleasant. When it burned down in January 1728, Lee replaced it with a still grander project on 1,400 acres along the Potomac that he named Stratford, purportedly in honor of an earlier Lee family estate in old Shropshire. He had expanded Stratford to 4,800 acres by 1750, and at its zenith it would embrace 6,600 acres, with a wharf for receiving and hauling cargoes, a warehouse, and a gristmill. Imposing family portraits would begin to line the paneled walls of Stratford’s central hall, bands of musicians would trumpet the beginning of balls from the quadruple chimneys, and Stratford’s master would preside “in great state.”10

There was, in fact, a good deal for the Lees to trumpet. Richard the Emigrant’s second son—also named Richard, but known as “the Scholar” for his bookish inclinations—married into the Corbin family, and the Corbins had a large role in steering the Fairfax agency into Thomas Lee’s hands. Thomas himself did well in the marriage mart, marrying Hannah Ludwell in 1722 (whose grandfather Philip had also been a loyal supporter of Governor Berkeley and even married Berkeley’s widow). So did his brother Henry, who developed a parallel establishment to Thomas’s Stratford property farther up the Neck at Freestone Point, which he named Leesylvania (and where he made the acquaintance of the young George Washington, the manager of his brother Augustine’s estate at Mount Vernon). But the apex of the Lee dynasty lay in the formidable array of sons born to Thomas and Hannah at Stratford—Philip Ludwell Lee (who inherited Stratford), Thomas Ludwell Lee, Richard Henry Lee (who was allowed to carve out a plantation of his own, Chantilly, from the Stratford property), Francis Lightfoot Lee (who parlayed his family connections into Virginia politics and married into one of the Neck’s other great families, the Tayloes of Mount Airy, on the Rappahannock side), and Arthur Lee and William Lee, who were both packed off to England for an education and life in finance and law.11

These advantages were fully matched by the Lees’ energies. Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee both served in the Continental Congress at the outbreak of the American Revolution and are the only brothers to appear as signers of the Declaration of Independence. Arthur Lee would turn into an outstanding diplomat in Spain and France (Samuel Johnson would regard him suspiciously in London for being “not only a patriot but an American”), and William Lee would represent American interests in the German states and Austria. Above all, it was Richard Henry Lee, “a tall, spare man” (as John Adams described him) who hid the left hand he had maimed in a shooting accident in a black silk glove, who would offer the climactic resolution in the Continental Congress in 1776: “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” Lee’s resolution, in turn, would become the core around which Thomas Jefferson would write the Declaration of Independence.12

The Northern Neck sparkled under the smile of the Lees, and not the Lees only. The Princeton College graduate Philip Vickers Fithian described it as a “most delightful Country; in a civil, polite neighbourhood.” If Virginia was considered “the garden of America,” the Northern Neck was “the garden spot of Virginia . . . possessing a very fertile soil, easily renovated by the marl which everywhere underlies it.” The Neck was home to nearly 6,900 taxpayers by the 1780s. The majority were landless tenants, while the average landholdings of all but 1 percent of the rest amounted to little more than 300 acres. But the Lees, at Stratford, at Leesylvania, and at Dividing Creek, were securely in the top bracket of the Neck’s wealth. They shared that pinnacle with several other Virginia dynasties on the Neck—the Tayloes at Mount Airy and Landon Carter at Sabine Hall, both of whose properties faced the Rappahannock, and Robert Carter’s Nomini Hall, and the Turbervilles at Hickory Hill, the nearer neighbors of Stratford and of Richard Henry Lee’s Chantilly.13

Much of the Lee wealth on the Neck was tied up in slaves, because none of the Lees had ever actually delved for their own bread on the land they engrossed with such unrelenting energy. The Lees, Tayloes, and Carters never owned fewer than 50 slaves each across the decades of the eighteenth century, while Robert Carter owned 345 slaves, John Tayloe 173, and George Turberville 68. Thomas Lee had, at varying times, owned between 60 and 100 slaves at Stratford, and as late as 1782, 83 slaves worked for Thomas Lee’s successors there.14

But these grandees were not necessarily prospering on their land. Although Virginians had made early fortunes in the seventeenth century through tobacco, the demand for the “Indian weed” declined throughout the eighteenth century, as had the nutrients in the soil of the Neck that supported it. Few people in England, complained Richard Henry Lee in the 1760s, understood “how much labour is required on a Virginean estate & how poor the produce.” Increasingly, the great plantations turned to growing wheat, fodder, and pork for export to the West Indies, where they could be fed to the slave and animal populations of the sugar islands whose vastly wealthier owners declined to waste arable sugar lands on growing food. Even more annoying, the West Indies trade was managed not by the planters themselves but by Scots and the factors whom they posted to the Neck, as ships from Glasgow, London, Bristol, and Whitehaven called at plantation landings along the Potomac and Rappahannock and bore off the Neck’s produce to feed other mouths. As they did, the white population of the Neck began to uproot, first for the Piedmont and the Shenandoah Valley, then still later for Kentucky and Tennessee.15

Copyright © 2021 by Allen C. Guelzo. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.