The Boy, 1980 Looks like rain,” you mutter to yourself.

What’ll we do if it really chucks it down?

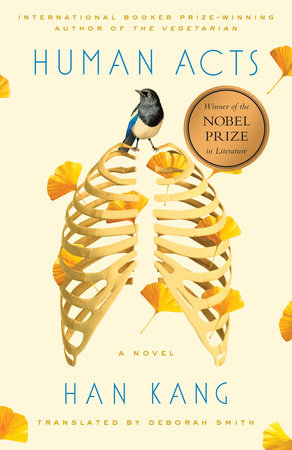

You open your eyes so that only a slender chink of light seeps in, and peer at the gingko trees in front of the Provincial Office. As though there, between those branches, the wind is about to take on visible form. As though the raindrops suspended in the air, held breath before the plunge, are on the cusp of trembling down, glittering like jewels.

When you open your eyes properly, the trees’ outlines dim and blur. You’re going to need glasses before long. This thought gets briefly disturbed by the whooping and applause that breaks out from the direction of the fountain. Perhaps your sight’s as bad now as it’s going to get, and you’ll be able to get away without glasses after all?

“Listen to me if you know what’s good for you: come back home, right this minute.”

You shake your head, trying to rid yourself of the memory, the anger lacing your brother’s voice. From the speakers in front of the fountain comes the clear, crisp voice of the young woman holding the microphone. You can’t see the fountain from where you’re sitting, on the steps leading up to the municipal gymnasium. You’d have to go around to the right of the building if you wanted to have even a distant view of the memorial service. Instead, you resolve to stay where you are, and simply listen.

“Brothers and sisters, our loved ones are being brought here today from the Red Cross hospital.”

The woman then leads the crowd gathered in the square in a chorus of the national anthem. Her voice is soon lost in the multitude, thousands of voices piling up on top of one another, a soaring tower of sound rearing up into the sky. The melody surges to a peak, only to swing down again like a pendulum. The low murmur of your own voice is barely audible.

This morning, when you asked how many dead were being transferred from the Red Cross hospital today, Jin-su’s reply was no more elaborate than it needed to be: thirty. While the leaden mass of the anthem’s refrain rises and falls, rises and falls, thirty coffins will be lifted down from the truck, one by one. They will be placed in a row next to the twenty-eight that you and Jin-su laid out this morning, the line stretching all the way from the gym to the fountain. Before yesterday evening, twenty-six of the eighty-three coffins hadn’t yet been brought out for a group memorial service; yesterday evening this number had grown to twenty-eight, when two families had appeared and each identified a corpse. These were then placed in coffins, with a necessarily hasty and improvised version of the usual rites. After making a note of their names and coffin numbers in your ledger, you added “group memorial service” in parentheses; Jin-su had asked you to make a clear record of which coffins had already gone through the service, to prevent the same ones being brought out twice. You’d wanted to go and watch, just this one time, but he told you to stay at the gym.

“Someone might come looking for a relative while the service is going on. We need someone manning the doors.”

The others you’ve been working with, all of them older than you, have gone to the service. Black ribbons pinned to the left-hand side of their chests, the bereaved who have kept vigil for several nights in front of the coffins now follow them in a slow, stiff procession, moving like scarecrows stuffed with sand or rags. Eun-sook had been hanging back, and when you told her, “It’s okay, go with them,” her laughter revealed a snaggle-tooth. Whenever an awkward situation forced a nervous laugh from her, that tooth couldn’t help but make her look somewhat mischievous.

“I’ll just watch the beginning, then, and come right back.”

Left on your own, you sit down on the steps that lead up to the gym, resting the ledger, an improvised thing whose cover is a piece of black strawboard bent down the middle, on your knee. The chill from the concrete steps leaches through your thin tracksuit bottoms. Your PE jacket is buttoned up to the top, and you keep your arms firmly folded across your chest.

Hibiscus and three thousand ri full of splendid mountains and rivers . . .

You stop singing along with the anthem. That phrase “splendid mountains and rivers” makes you think of the second character in “splendid,” “ryeo,” one of the ones you studied in your Chinese script lessons. It’s got an unusually high stroke count; you doubt you could remember how to write it now. Does it mean “mountains and rivers where the flowers are splendid,” or “mountains and rivers that are splendid as flowers”? In your mind, the image of the written character becomes overlaid with that of hollyhocks, the kind that grow in your parents’ yard, shooting up taller than you in summer. Long, stiff stems, their blossoms unfurling like little scraps of white cloth. You close your eyes to help you picture them more clearly. When you let your eyelids part just the tiniest fraction, the gingko trees in front of the Provincial Office are shaking in the wind. So far, not a single drop of rain has fallen.

The anthem is over, but there seems to be some delay with the coffins. Perhaps there are just too many. The sound of wailing sobs is faintly audible amid the general commotion. The woman holding the microphone suggests they all sing “Arirang” while they wait for the coffins to be got ready.

You who abandoned me here

Your feet will pain you before you’ve gone even ten ri . . .

When the song subsides, the woman says, “Let us now hold a minute’s silence for the deceased.” The hubbub of a crowd of thousands dies down as instantaneously as if someone had pressed a mute button, and the silence it leaves in its wake seems shockingly stark. You get to your feet to observe the minute’s silence, then walk up the steps to the main doors, one half of which has been left open. You get your surgical mask out from your trouser pocket and put it on.

These candles are no use at all.

You step into the gym hall, fighting down the wave of nausea that hits you with the stench. It’s the middle of the day, but the dim interior is more like evening’s dusky half-light. The coffins that have already been through the memorial service have been grouped neatly near the door, while at the foot of the large window, each covered with a white cloth, lie the bodies of thirty-two people for whom no relatives have yet arrived to put them in their coffins. Next to each of their heads, a candle wedged into an empty drinks bottle flickers quietly.

You walk farther into the auditorium, toward the row of seven corpses that have been laid out to one side. Whereas the others have their cloths pulled up only to their throats, almost as though they are sleeping, these are all fully covered. Their faces are revealed only occasionally, when someone comes looking for a young girl or a baby. The sight of them is too cruel to be inflicted otherwise.

Even among these, there are differing degrees of horror, the worst being the corpse in the very farthest corner. When you first saw her, she was still recognizably a smallish woman in her late teens or early twenties; now, her decomposing body has bloated to the size of a grown man. Every time you pull back the cloth for someone who has come to find a daughter or younger sister, the sheer rate of decomposition stuns you. Stab wounds slash down from her forehead to her left eye, her cheekbone to her jaw, her left breast to her armpit, gaping gashes where the raw flesh shows through. The right side of her skull has completely caved in, seemingly the work of a club, and the meat of her brain is visible. These open wounds were the first to rot, followed by the many bruises on her battered corpse. Her toes, with their clear pedicure, were initially intact, with no external injuries, but as time passed they swelled up like thick tubers of ginger, turning black in the process. The pleated skirt with its pattern of water droplets, which used to come down to her shins, doesn’t even cover her swollen knees now.

You come back to the table by the door to get some new candles from the box, then return to the body in the corner. You light the cloth wicks of the new candle from the melted stub guttering by the corpse. Once the flame catches, you blow out the dying candle and remove it from the glass bottle, then insert the new one in its place, careful not to burn yourself.

Your fingers clutching the still-warm candle stub, you bend down. Fighting the putrid stink, you look deep into the heart of the new flame. Its translucent edges flicker in constant motion, supposedly burning up the smell of death that hangs like a pall in the room. There’s something bewitching about the bright orange glow at its heart, its heat evident to the eye. Narrowing your gaze even further, you center in on the tiny blue-tinged core that clasps the wick, its trembling shape recalling that of a heart, or perhaps an apple seed.

You straighten up, unable to stand the smell any longer. Looking around the dim interior, you drag your gaze lingeringly past each candle as it wavers by the side of a corpse, the pupils of quiet eyes.

Suddenly it occurs to you to wonder, when the body dies, what happens to the soul? How long does it linger by the side of its former home?

Copyright © 2017 by Han Kang. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.