Foreword“A secret, a secret, I’ve got a little secret.” Cécile McLorin Salvant flashes a grin as she sings this playful taunt, the preamble to an old show tune, “If This Isn’t Love.” She’s at the Village Vanguard, which has entered its ninth decade with an indisputable reputation as the most hallowed jazz club in the world. In a couple of days Salvant would release a double album largely recorded in this room. But she doesn’t so much as mention it during the set. Her only partner onstage is the pianist Sullivan Fortner, and she seems determined to meet him in an elegant free fall, making adjustments and testing out methods on the fly.

The burden of jazz history lies in wait for a moment like this. Headlining the Vanguard to a sold-out crowd without a proven set list is a recipe for all manner of anxiety, not least the anxiety of influence. But over the course of her casually stunning performance, on a late-September evening in 2017, Salvant shows that she’s neither wrestling with ghosts nor shouldering a weight of obligation. Instead, she carries herself like the beneficiary of a trust: she’s got a little secret, and she’s letting her audience in on the action.

She knows better than anyone in the club that “If This Isn’t Love” was a calling card for the sublime jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, who recorded her definitive version in the 1950s. There’s a hint of Vaughan in Salvant’s bell-like tone and swooping inflection, but also abundant creative liberties in her phrasing. Rather than evoke the past from a stance of decorum or deference, Salvant is bent on stirring it up with sly intellectual rigor. Given how much effort has gone into the canonization of the jazz tradition, she’s a stealth subversive, working within a recognizable framework in ways that feel ecstatic and unbound.

The emergence of a jazz artist as audacious, unconflicted, and grounded as Salvant, at this stage in the game, suggests both the fulfillment of a promise and the rejection of an idea. During the waning phase of the last century, jazz was enshrined in the popular imagination as a historical practice, a set of codes to be reenacted endlessly. Market forces—primed by a relentless campaign of reissues and compilations, tributes and emulations—had fed a common perception that the music reached its peak in a distant golden age. What could Salvant possibly be if not a throwback? The art form had already completed a full life cycle of creation, maturation, obsolescence, and revival.

Gary Giddins, the astute jazz critic, once delineated that trajectory in an essay with a cheeky title, “How Come Jazz Isn’t Dead?” In it, he argues that the development of any musical form can be divided into four stages. The first is Native, followed by Sovereign. Then comes Recessionary. Finally, we arrive at Classical—when “Even the most adventurous young musicians are weighed down by the massive accomplishments of the past.”

Most mainstream narratives of jazz over the last several decades followed the general contour of this model. Critics and historians, planting their surveying equipment on Classical bedrock, took their measure of the music along a timeline. So it was no surprise that the conventional framework suggested an inexorable march of progress. And it made sense that jazz, especially for those outside its orbit, meant something openly retrograde. When Giddins updated his four-stage paradigm in 2009 for

Jazz, a sprawling history coauthored with the scholar Scott DeVeaux, he suggested that it might help to envision the music in a “post-historical” mode. That notion seems almost custom-fitted to Salvant, with her refusal to be typecast by precedent.

But she’s just one figure in a vast new complex, the dimensions of which make the four-stage paradigm feel reductive. What the most recent jazz surveys and histories tend to ignore is an explosion of new techniques, accents, and protocols that define the state of the art in our time. Some of this happened in response to widespread upheaval. As the art form began to settle into its second century, its practitioners faced tougher conditions than any previous generation: a broken infrastructure, an uncertain course, a distracted, if not alienated, consumer base.

But more than one wave of improvising artists has confronted this tumult, seizing license to create freer and more self-reliant forms of art. Raised with unprecedented access to information, they scour jazz history not for a linear narrative but a network of possibilities. Their frame of reference is broad enough to encourage every form of hybridism. They understand jazz as something other than a stable category. And their work has evolved the music—insofar as harmonic color, dynamic flow, group interaction, and a complex yet streamlined expression of rhythm are concerned.

Jazz has always been a frontier of inquiry, with experimentation in multiple registers. That’s as true now as it has ever been. But to a striking degree, avant-garde practice and formal invention have now insinuated themselves into the mainstream, shifting the music’s aesthetic center. Not even a resurgent strain of hot-jazz antiquarianism—the province of out-and-proud nostalgists—can stem the current trend toward polyglot hypermodernism, toward unexpected composites and convergences.

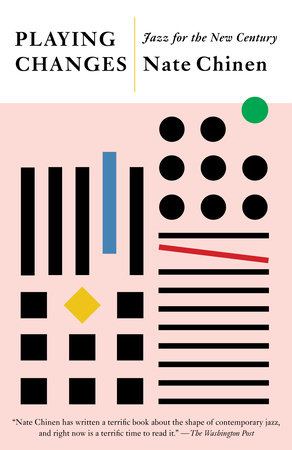

This book begins with a reflection on the crisis of confidence that distorted jazz’s ecology during the late phases of the twentieth century. Tracing a historicist agenda that actualized in the 1970s, mobilized in the 1980s, and all but tyrannized the 1990s, this narrative sets an important context for our present moment of abundance. As the music transitioned out of the last century, it became increasingly clear that a conscientious foothold in tradition could work in peaceful tandem with many approaches that fall outside a strict definition of jazz. The whole idea of a definition, in fact, was beginning to feel outmoded. Whatever you choose to call the music, “jazz” is as volatile and generative now as at any time since its beginnings. Instead of stark binaries and opposing factions, we face a blur of contingent alignments. Instead of a push for definition and one prevailing style, we have boundless permutations without fixed parameters. That multiplicity lies precisely at the heart of the new aesthetic—and is the engine of its greatest promise.

Copyright © 2018 by Nate Chinen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.