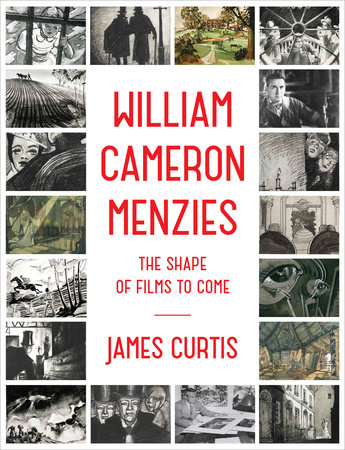

In the year 1963, Alfred Hitchcock was questioned by an earnest young interviewer who said that he presumed that all of Hitchcock’s films were “pre-designed by an art director.” Did he, in fact, do all the drawings himself?

“Well,” said Hitchcock, “art director is not a correct term.

You see, an art director, as we know it in the studios, is a man who designs a set. The art director seems to leave the set before it’s dressed and a new man comes on the set called the set dresser. Now, there is another function which goes a little further beyond the art director and is almost in a different realm. That is the production designer. Now, a production designer is a man

usually who designs angles and sometimes production ideas. Treatment of action. There used to be a man . . . is he still alive? William Cameron Menzies. No, he’s not. Well, I had William Cameron Menzies on a picture called

Foreign Correspondent and he would take a sequence, you see, and by a series of sketches indicate camera setups. Now this is, in a way, nothing to do with art direction. The art director is set designing. Production design is definitely taking a sequence and laying it out in sketches.

With the completion of

Rebecca, Selznick closed his studio for an extended period, ultimately liquidating Selznick International in order to draw down the substantial profits generated by

Gone With the Wind. He began selling off the properties he owned—

The Keys of the Kingdom and

Claudia, among others—and loaning his contract talent to other producers. Vivien Leigh and Ingrid Bergman were sent to M-G-M while his one director, Hitchcock, was lent to producer Walter Wanger. The deal with Wanger was concluded on October 2, 1939, establishing Hitchcock as the director of Vincent Sheean’s memoir

Personal History, a property that had been under development since 1935.

Considering the book dated and unsuited to his particular strengths as a storyteller, Hitchcock, in collaboration with his wife, Alma Reville, and his secretary, Joan Harrison, devised an entirely new plotline which carried Sheean’s title from the book and little else. Eventually, the title, too, would be dropped, the film instead drawing its name from Sheean’s longtime profession—

Foreign Correspondent. By the time Menzies came aboard in March, reportedly at Hitchcock’s behest, a total of twenty-two writers had contributed to the script, including John Howard Lawson, Budd Schulberg, John Meehan, James Hilton, Ben Hecht, and Robert Benchley. Indeed, Selznick may have had a hand in putting the two men together, as Hitchcock had never before tackled a picture as big or as complex. Selznick was also keen to establish a demand for his British import, whose last released picture in the United States was

Jamaica Inn—a dud.

Menzies found that Hitchcock, himself a former art director, was in the habit of making rough pencil sketches on his copy of the script. Menzies, in turn, worked out more than a hundred oversized drawings of sets and action for the start of production, as well as models of a dozen sets. When shooting began on March 18, 1940, the film was already four months behind schedule and progress was, at times, agonizingly slow. Menzies later recalled “a rather unpleasant association with Hitch” that nevertheless yielded “some pretty good results.” Among the principal sequences was a plane crash staged in the same manner as the dirigible crash in

The Lottery Bride. “I hardly used any miniatures at all,” said Menzies, “but did the whole thing objectively, that is from a point of view always inside the cabin. I also had a very interesting sequence in a windmill where we really got some good photographic effects, and an assassination sequence in Amsterdam in the rain, which I rather borrowed from

Our Town.”

The huddle of black umbrellas to represent Emily’s funeral cortege was a memorable feature of Jed Harris’ original stage production, and Menzies had elaborated on it, gathering the canopies, glistening in the rainfall, in the foreground of the shot and allowing the night sky to fully occupy the upper half of the frame. There had never been a more spiritual composition for the talking screen, and now Menzies took the same basic elements, expanded their numbers exponentially to fill a public square, and clustered them to emphasize the particularly brazen murder of a Dutch diplomat, an event that sends John Jones in pursuit of the killer, an adventure similar in substance and pacing to the director’s earlier

39 Steps. The windmill scenes were shot during the first days of production and afforded a kinetic maze of hazards and hiding places, the actors confined to a claustrophobic tangle of stairways and gears, the protagonist (Joel McCrea) eluding Nazi agents while attempting to rescue the drugged and disoriented Van Meer, whose memory holds the critical clause of an allied peace treaty. Menzies estimated he made “about 200 drawings” for

Foreign Correspondent, roughly a quarter of the number he typically did for a feature, implying he worked primarily on the film’s complex set pieces.

“It was my observation,” said actress Laraine Day, “that Mr. Hitchcock and Mr. Menzies conferred on every shot that had been drawn by Mr. Menzies. Whether or not there was a storyboard for the entire production, I don’t really know, but it would seem reasonable to believe that if every scene was drawn before it was filmed, there must have been a storyboard from which these individual scene depictions were taken for them to discuss. Their working relationship during

Foreign Correspondent seemed very close.”

The crash, much more elaborate in design and execution than its 1930 predecessor, formed the basis for the climax of the picture. And unlike the dirigible crash in

Lottery Bride, which took place in frozen environs of the Arctic Circle, the downing of the clipper in

Foreign Correspondent takes place over the ocean. “The whole thing was done in a

single shot without a cut!” marveled Hitchcock in his marathon 1962 interview with François Truffaut. “I had a transparency screen made of paper, and behind that screen, a water tank. The plane dived, and as soon as the water got close to it, I pressed the button and the water burst through, tearing the screen away. The volume was so great that you never saw the screen.”

The teaming of Alfred Hitchcock and William Cameron Menzies proved an inspired melding of two vastly different artistic sensibilities, Hitchcock being interested in the conveyance of visual information, Menzies in the deepening of the film’s graphic impact. Together, they produced one of the grand thrillers of the sound era. When production closed on May 29, 1940, after sixty-five days of shooting and eleven days of retakes, the negative cost of

Foreign Correspondent stood at $1,484,167—by far the most expensive picture Hitchcock had ever made.

Copyright © 2015 by James Curtis. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.