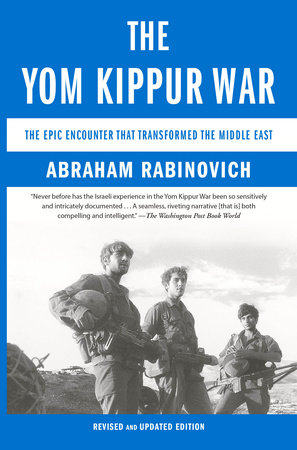

1

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SAND Capt. Motti Ashkenazi was not a man to accept a perceived wrong without protest. The outpost in Sinai that his unit of reservists was taking over two weeks before Yom Kippur 1973 was in an advanced state of neglect. Barbed wire fencing had sunk almost entirely into the sand, trenches were collapsing, gun positions lacked sandbags, and the ammunition supply was short. When the commander of the unit he was relieving asked him to sign the standard form acknowledging receipt of the outpost in good condition, Ashkenazi balked. Without this formality, the unit being relieved could not depart. When Ashkenazi refused an order from his own battalion commander to sign, the exasperated commander signed the form himself.

The battalion was part of the Jerusalem Brigade, which had never before been assigned to a tour of duty on the Suez Canal. Unlike the combat units that were normally assigned to the forts of the so-called Bar-Lev Line, the Jerusalem Brigade was a second-line unit which included men well into their thirties. Some were immigrants who had received only a truncated form of basic training. A sprinkling of younger reservists with combat experience stiffened the ranks and officers too were generally veterans of combat units.

The assignment of such a unit to the Bar-Lev Line, once considered hazardous duty, reflected the relaxed situation on the Egyptian front. It was six years since Israel had reached the canal in the Six Day War and three years since the intense skirmishing across the waterway—the so-called War of Attrition—had ended.

The reservists grumbled as usual upon receiving their annual call-up notices for a month’s duty, particularly since their tour was beginning on the eve of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, and would last through Yom Kippur and the subsequent Sukkot holiday. However, by the time they boarded the buses that would take them to Sinai, many had reconciled themselves to a month of camaraderie, far from the routine of work and home. The men brought books and board games, finjans for brewing coffee, even fishing rods. Ashkenazi, a thirty-two-year-old doctoral student in philosophy at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, took along his four-month-old German shepherd, Peng, because he had nowhere to leave him.

Unlike the other Bar-Lev forts, which were built along the canal bank, Ashkenazi’s outpost, code-named Budapest, was ten miles east of the canal on a narrow sand spit between the Mediterranean and a shallow lagoon. The outpost’s purpose was to guard against an Egyptian thrust along the sand spit toward the coastal road leading to Israel. Budapest was the largest of the Bar-Lev Line fortifications, incorporating an artillery battery and a naval signals unit which maintained contact with vessels patrolling off the coast.

Toward evening on the day of his arrival, Ashkenazi, a deputy company commander, climbed the fort’s observation tower and looked west along the sand spit. This northwest corner of Sinai was the only part of the Sinai Peninsula Israel had not gotten around to capturing in the 1967 war. Ashkenazi could make out a string of Egyptian outposts stretching toward Port Fuad, which, together with Port Said, straddled the northern entrance to the Suez Canal. The outpost closest to him was only a mile away. Since the canal did not separate them, the only thing that could inhibit an Egyptian raid was a minefield that Budapest’s previous commander had pointed out to him during their tour that morning.

As Ashkenazi watched, a pack of wild dogs emerged from the Egyptian lines and trotted down the sands in his direction. They appeared to be heading toward Budapest’s garbage dump at the western edge of the position. As they approached the minefield, Ashkenazi braced for explosions. But the dogs passed through unharmed. Tides washing over the sands had apparently dislodged or neutralized the mines. Ashkenazi decided to contact battalion headquarters in the morning to request additional fencing and sandbags.

###

Maj. Meir Weisel, an affable kibbutznik, was the most senior company commander in the battalion which moved into the Bar-Lev Line. In previous tours of reserve duty, his unit had clashed with Palestinian guerrillas along the Jordan River and taken casualties. “This time,” a Jerusalem Brigade officer had told him when he reported for duty a few days before, “I’m sending you to the canal and you can rest.” His company took over four forts in the canal’s central sector. He positioned himself in Fort Purkan, opposite the city of Ismailiya on the Egyptian-held bank. The officer whom he replaced pointed out a villa across the canal that he said had belonged to the parents of Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban’s wife, Suzie, who was from a prominent Egyptian Jewish family. It was not clear who lived there now but someone watered the plants every day. “As long as you see the gardener working there,” said the officer, “everything is okay.”

The limited forces Israel deployed on both the Syrian and Egyptian fronts opposite vastly larger enemy armies reflected a self-assurance stemming from the country’s stunning victory in the Six Day War. Israel believed it had attained a military superiority that no Arab nation or combination of nations could challenge. The euphoria that followed that lightning victory in 1967 over the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian armies gave Israel a sense of manifest destiny similar to that which impelled the United States westward in the nineteenth century. The Six Day War had been launched from within Israel’s narrow borders that Eban had termed “Auschwitz borders,” an allusion to their vulnerability. The post–Six Day War cease-fire lines for the first time provided Israel strategic depth.

Israel had twice as many tanks and warplanes in 1973 as it had in the Six Day War. Its largest armor formations were no longer brigades with a hundred tanks but divisions with three hundred. Veteran armor officers permitted themselves to fantasize commanding a division deploying into battle—two brigades forward, one to the rear, as they swept into the attack.

The armies of Egypt and Syria had grown more than Israel’s in absolute numbers but the overall ratio in the Arab favor remained 3 to 1. Given the proven fighting ability of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), this ratio was considered acceptable in Israel. The General Staff, in fact, was preparing to reduce the thirty-six months of service required of its conscript soldiers by three months. Convinced that it could hold its own against an Arab world thirty times its size, Israel was waiting for the Arabs to formally recognize the Jewish state and agree to new borders.

The Arab world, however, refused to accept the humiliation of 1967. In the War of Attrition launched by Egypt in March 1969, hundreds of Israeli soldiers died in massive artillery bombardments. Deep penetration raids by Israeli warplanes and commandos forced Cairo to accept a cease-fire in August 1970. Since then, the Suez front had remained quiet. On the Syrian front, there were periodic exchanges of fire—“battle days,” Israel termed them—but no serious challenge to Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights.

The seeming docility of the Arabs encouraged a sense of invulnerability. In August 1973, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, in a speech to army officers, said that Israel’s strength was a reflection not only of its increasing military potential but of inherent Arab weakness. “It is a weakness that derives from factors that I don’t believe will change quickly: the low level of their soldiers in education, technology, and integrity; and inter-Arab divisiveness which is papered over from time to time but superficially and for short spans.”

A Mossad official, Reuven Merhav, who had been posted abroad immediately after the Six Day War, returned home five years later to find the country transformed. Israel was not just self-assured, he found, but self-satisfied, awash in a good life that seemed as if it would go on forever. Government and military officials traveled now in large cars and wrote off business lunches to expenses, a new practice. Arabs from the West Bank and Gaza Strip provided the working hands the fast-growing nation needed but were politically invisible. The sense of physical expanse was startling to someone accustomed to the claustrophobia of pre–Six Day War Israel. The border was no longer fifteen minutes from Tel Aviv or on the edge of Jerusalem but out of sight and almost out of mind—on the Jordan River, the Suez Canal, the Golan. People went down to Sinai now not to wage war but to holiday on its superb beaches.

The army had grown not just physically but in its prominence in national life. There was now a layer of brigadier generals, a newly created rank required by the army’s expansion. The Mossad officer sensed arrogance in high places. Some generals ordered their offices redone to reflect their new status, some gave parties with army entertainment troupes singing in the background. All of this was foreign to the spartan ways Merhav had known as distinguishing features of Israeli public life only five years before. An attitude of disdain for Arab military capability had etched itself insidiously into the national psyche. The official was as yet unaware of the extent to which this disdain had led to distortions in the professional mind-set of the armed forces.

###

Sitting in a downtown Jerusalem café a few months before the war, Motti Ashkenazi told a friend that war was inevitable unless Israel accepted Egypt’s demand that it pull back from the canal in order to permit the waterway to be reopened. Now, in command of Budapest, he took his own warning seriously. After two days of badgering battalion headquarters, he was informed that his request for sandbags and barbed wire concertinas was being met. The supply vehicle that arrived carried only a fraction of what he had asked for. Nevertheless, he was able to fortify the area around the fort’s gate and the vulnerable approach from the beach.

A week before Yom Kippur, Ashkenazi was in a half-track making a routine morning patrol eastward along the sand spit toward his rear base when he saw fresh footprints in the sand on both sides of the road. Whoever made them seemed to have circled the area, as if examining the lay of the land. The road between Budapest and rear headquarters was closed off every night because it was vulnerable to commando landings from the sea. If anyone came down the road by day, Budapest was supposed to be informed beforehand, but there had been no such notification. The footprints, thought Ashkenazi, could have been left by Egyptian scouts landing from the sea, on one side of the road, or coming on foot through the lagoon, on the other side. He radioed headquarters and a vehicle with two Bedouin trackers arrived. They examined the footprints and concluded that they had been made by standard Israeli army boots.

“If I were an Egyptian scout, I would use that kind of boot,” said Ashkenazi.

The trackers laughed. “Do you think they’re that clever?”

“Why not?” asked Ashkenazi.

Twice more in the coming days he would find footprints along the route.

Copyright © 2004 by Abraham Rabinovich. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.