Moment: A Definition

narrator: On November fourteenth, nineteen ninety-eight, the members of Tectonic Theater Project traveled to Laramie, Wyoming, and conducted interviews with the people of the town. During the next year, we would return to Laramie several times and conduct over two hundred interviews. The play you are about to see is edited from those interviews, as well as from journal entries by members of the company and other found texts. Company member Greg Pierotti.

greg pierotti: My first interview was with Detective Sergeant Hing of the Laramie Police Department. At the start of the interview he was sitting behind his desk, sitting something like this (he transforms into Sergeant Hing):

I was born and raised here.

My family is, uh, third generation.

My grandparents moved here in the early nineteen hundreds.

We’ve had basically three, well, my daughter makes it fourth generation.

Quite a while. . . . It’s a good place to live. Good people— lots of space.

Now, all the towns in southern Wyoming are laid out and spaced because of the railroad came through. It was how far they could go before having to refuel and rewater. And, uh, Laramie was a major stopping point. That’s why the towns are spaced so far apart. We’re one of the largest states in the country, and the least populated.

rebecca hilliker: There’s so much space between people and towns here, so much time for reflection.

narrator: Rebecca Hilliker, head of the theater department at the University of Wyoming.

rebecca hilliker: You have an opportunity to be happy in your life here. I found that people here were nicer than in the Midwest, where I used to teach, because they were happy. They were glad the sun was shining. And it shines a lot here.

sergeant hing: What you have is, you have your old-time traditional-type ranchers, they’ve been here forever—Laramie’s been the hub of where they come for their supplies and stuff like that.

eileen engen: Stewardship is one thing all our ancestors taught us.

narrator: Eileen Engen, rancher.

eileen engen: If you don’t take care of the land, then you ruin it and you lose your living. So you first of all have to take care of your land and do everything you can to improve it.

doc o’connor: I love it here.

narrator: Doc O’Connor, limousine driver.

doc o’connor: You couldn’t put me back in that mess out there back east. Best thing about it is the climate. The cold, the wind. They say the Wyoming wind’ll drive a man insane. But you know what? It don’t bother me. Well, some of the times it bothers me. But most of the time it don’t.

sergeant hing: And then you got uh, the university population.

philip dubois: I moved here after living in a couple of big cities.

narrator: Philip Dubois, president of the University of Wyoming.

philip dubois: I loved it there. But you’d have to be out of your mind to let your kids out after dark. And here, in the summertime, my kids play out at night till eleven and I don’t think twice about it.

sergeant hing: And then you have the people who live in Laramie, basically.

zackie salmon: I moved here from rural Texas.

narrator: Zackie Salmon, Laramie resident.

zackie salmon: Now, in Laramie, if you don’t know a person, you will definitely know someone they know. So it can only be one degree removed at most. And for me—I love it! I mean, I love to go to the grocery store ’cause I get to visit with four or five or six people every time I go. And I don’t really mind people knowing my business—’cause what’s my business? I mean, my business is basically good.

doc o’connor: I like the trains, too. They don’t bother me. Well, some of the times they bother me, but most times they don’t. Even though one goes by every thirteen minutes out where I live. . . .

narrator: Doc actually lives up in Bossler. But everybody in Laramie knows him. He’s also not really a doctor.

doc o’connor: They used to carry cattle . . . them trains. Now all they carry is diapers and cars.

april silva: I grew up in Cody, Wyoming.

narrator: April Silva, university student.

april silva: Laramie is better than where I grew up. I’ll give it that.

sergeant hing: It’s a good place to live. Good people, lots of space. Now, when the incident happened with that boy, a lot of press people came here. And one time some of them followed me out to the crime scene. And uh, well, it was a beautiful day, absolutely gorgeous day, real clear and crisp and the sky was that blue that, uh . . . you know, you’ll never be able to paint, it’s just sky blue—it’s just gorgeous. And the mountains in the background and a little snow on ’em, and this one reporter, uh, lady . . . person, that was out there, she said . . .

reporter: Well, who found the boy, who was out here anyway?

sergeant hing: And I said, “Well, this is a really popular area for people to run, and mountain biking’s really big out here, horseback riding, it’s just, well, it’s close to town.” And she looked at me and she said:

reporter: Who in the hell would want to run out here?

sergeant hing: And I’m thinking, “Lady, you’re just missing the point.” You know, all you got to do is turn around, see the mountains, smell the air, just take in what’s around you. And they were just—nothing but the story. I didn’t feel judged, I felt that they were stupid. They’re, they’re missing the point—they’re just missing the whole point.

jedadiah schultz: It’s hard to talk about Laramie now, to tell you what Laramie is, for us.

narrator: Jedadiah Schultz, university student.

jedadiah schultz: If you would have asked me before, I would have told you Laramie is a beautiful town, secluded enough that you can have your own identity. . . . A town with a strong sense of community—everyone knows everyone. . . . A town with a personality that most larger cities are stripped of. Now, after Matthew, I would say that Laramie is a town defined by an accident, a crime. We’ve become Waco, we’ve become Jasper. We’re a noun, a definition, a sign!

Moment: Journal Entries

narrator: Journal entries—members of the company. Andy Paris.

andy paris: Moisés called saying he had an idea for his next theater project. But there was a somberness to his voice, so I asked what it was all about and he told me he wanted to do a piece about what’s happening in Wyoming.

narrator: Stephen Belber.

stephen belber: Leigh told me the company was thinking of going out to Laramie to conduct interviews and that they wanted me to come. But I’m hesitant. I have no real interest in prying into a town’s unraveling.

narrator: Amanda Gronich.

amanda gronich: I’ve never done anything remotely like this in my life. How do you get people to talk to you? What do you ask?

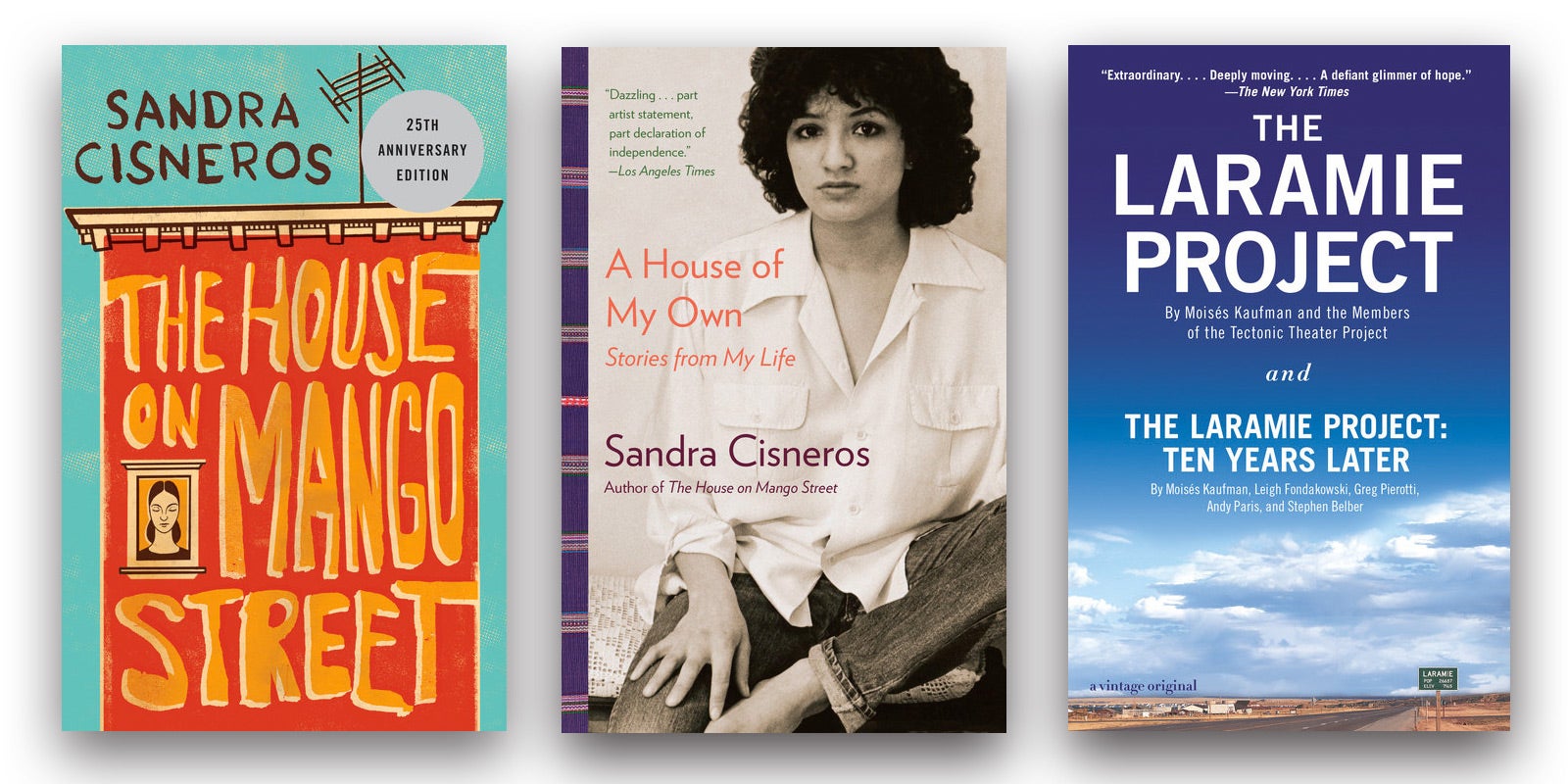

narrator: Moisés Kaufman.

moisés kaufman: The company has agreed that we should go to Laramie for a week and interview people.

Am a bit afraid about taking ten people in a trip of this nature. Must make some safety rules. No one works alone. Everyone must carry a cell phone. Have made some preliminary contacts with Rebecca Hilliker, head of the theater department at the University of Wyoming. She is hosting a party for us our first night in Laramie and has promised to introduce us to possible interviewees.

Moment: Rebecca Hilliker

rebecca hilliker: I must tell you that when I first heard that you were thinking of coming here, when you first called me, I wanted to say you’ve just kicked me in the stomach. Why are you doing this to me?

But then I thought, That’s stupid, you’re not doing this to me. And more importantly, I thought about it and decided that we’ve had so much negative closure on this whole thing. And the students really need to talk. When this happened they started talking about it, and then the media descended and all dialogue stopped.

You know, I really love my students because they are free thinkers. And you may not like what they have to say, and you may not like their opinions, because they can be very redneck, but they are honest and they’re truthful—so there’s an excitement here that I never had when I was in the Midwest or in North Dakota, because there, there was so much Puritanism that dictated how people looked at the world that a lot of times they didn’t have an opinion, you couldn’t get them to express an opinion. And, quite honestly, I’d rather have opinions that I don’t like—and have that dynamic in education.

There’s a student I think you should talk to. His name is Jedadiah Schultz.

Moment: Angels in America

jedadiah schultz: I’ve lived in Wyoming my whole life. The family has been in Wyoming well . . . for generations. Now when it came time to go to college, my parents can’t—couldn’t afford to send me to college. I wanted to study theater. And I knew that if I was going to go to college I was going to have to get on a scholarship—and so uh they have this competition each year, this Wyoming state high school competition. And I knew that if I didn’t take first place in uh duets that I wasn’t gonna get a scholarship. So I went to the theater department of the university looking for good scenes and I asked one of the professors, I was like, “I need—I need a killer scene,” and he was like, “Here you go, this is it.” And it was from Angels in America.

So I read it and I knew that I could win best scene if I did a good enough job.

And when the time came I told my mom and dad so that they would come to the competition. Now you have to understand, my parents go to everything—every ball game, every hockey game—everything I’ve ever done.

And they brought me into their room and told me that if I did that scene, that they would not come to see me in the competition. Because they believed that it is wrong—that homosexuality is wrong. They felt that strongly about it that they didn’t want to come see their son do probably the most important thing he’d done to that point in his life. And I didn’t know what to do.

I had never, ever gone against my parents’ wishes. But I decided to do it.

And all I can remember about the competition is that when we were done me and my scene partner, we came up to each other and we shook hands and there was a standing ovation.

Oh, man, it was amazing! And we took first place and we won. And that’s how come I can afford to be here at the university, because of that scene. It was one of the best moments of my life. And my parents weren’t there. And to this day, that was the one thing that my parents didn’t see me do.

And thinking back on it, I think, why did I do it? Why did I oppose my parents? ’Cause I’m not gay. So why did I do it? And I guess the only honest answer I can give is that, well (he chuckles) I wanted to win. It was such a good scene; it was like the best scene!

Do you know Mr. Kushner? Maybe you can tell him.

Moment: Journal Entries

narrator: Company member Greg Pierotti.

greg pierotti: We arrived today in the Denver Airport and drove to Laramie—

The moment we crossed the Wyoming border I swear I saw a herd of buffalo.

Also, I thought it was strange that the Wyoming sign said:

wyoming—like no place on earth instead of

wyoming—like no place else on earth.

narrator: Company member Leigh Fondakowski.

leigh fondakowski: I stopped at a local inn for a bite to eat. And my waitress said to me:

waitress: Hi, my name is Debbie. I was born in nineteen fifty-four and Debbie Reynolds was big then, so yes, there are a lot of us around, but I promise that I won’t slap you if you leave your elbows on the table.

moisés kaufman: Today Leigh tried to explain to me to no avail what chicken fried steak was.

waitress: Now, are you from Wyoming? Or are you just passing through?

leigh fondakowski: We’re just passing through.

narrator: Company member Barbara Pitts.

barbara pitts: We arrived in Laramie tonight. Just past the welcome to laramie sign—population 26,687—the first thing to greet us was Wal-Mart. In the dark, we could be on any main drag in America—fast-food chains, gas stations. But as we drove into the downtown area by the railroad tracks, the buildings still looked like the shape of a turn-of-the-century western town. Oh, and as we passed the University Inn, on the sign where amenities such as heated pool or cable TV are usually touted, it said: hate is not a laramie value.

narrator: Greg Pierotti.

Moment: Alison and Marge

greg pierotti: I met today with two longtime Laramie residents, Alison Mears and Marge Murray, two social service workers who taught me a thing or two.

alison mears: Well, what Laramie used to be like when Marge was growing up, well, it was mostly rural.

marge murray: Yeah, it was. I enjoyed it, you know. My kids all had horses.

alison mears: Well, there was more land, I mean, you could keep your pet cow. Your horse. Your little chickens. You know, just have your little bit of acreage.

marge murray: Yeah, I could run around the house in my altogethers, do the housework while the kids were in school. And nobody could see me. And if they got that close . . .

alison mears: Well, then that’s their problem.

marge murray: Yeah.

greg pierotti: I just want to make sure I got the expression right: “in your altogethers”?

marge murray: Well, yeah, honey, why wear clothes?

alison mears: Now, how’s he gonna use that in his play?

greg pierotti: So this was a big ranching town?

alison mears: Oh, not just ranching, this was a big railroad town at one time. Before they moved everything to Cheyenne and Green River and Omaha. So now well, it’s just a drive-through spot for the railroad—because even what was it, in the fifties? Well, they had one big roundhouse, and they had such a shop they could build a complete engine.

marge murray: They did, my mom worked there.

greg pierotti: Your mom worked in a roundhouse?

marge murray: Yep. She washed engines. Her name was Minnie. We used to, you know, sing that song for her, you know that song.

greg pierotti: What song?

marge murray: “Run for the roundhouse, Minnie, they can’t corner you there.”

(They crack up.)

alison mears: But I’ll tell you, Wyoming is bad in terms of jobs. I mean, the university has the big high whoop-dee-doo jobs. But Wyoming, unless you’re a professional, well, the bulk of the people are working minimum-wage jobs.

Copyright © 2014 by Moises Kaufman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.