CHAPTER 1

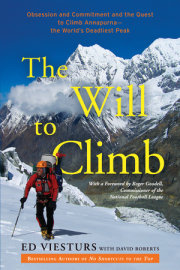

Self–

ArrestAt last things seemed to be going our way. Inside our Camp III tent, at 24,300 feet, Scott Fischer and I crawled into our sleeping bags and turned off our headlamps. The next day, we planned to climb up to Camp IV, at 26,000 feet. On the day after, we would get up in the middle of the night, put on all our clothing, grab our gear and a little food, and set off for the summit of K2, at 28,250 feet the second-highest mountain in the world. From Camp IV, the 2,250 vertical feet of snow, ice, and rock that would stretch between us and the top could take as long as twelve hours to climb, since neither Scott nor I was using supplemental oxygen. We had agreed that if we hadn’t reached the summit by two P.M., we’d turn around—no matter what. * It was the evening of August 3, 1992. Fifty-four days earlier, we had started our hike in to base camp on the Baltoro Glacier, which we had reached on June 21. Before the trip, even in my most pessimistic scenario I had never imagined that it could take us more than six weeks just to get in position for a summit push. But this expedition had seemed jinxed from the start—by hideous weather, by minor but consequential accidents, by an almost chaotic state of disorganization within our team.

As usual in the midst of a several-day summit push at high altitude, Scott and I were too keyed up to fall asleep. We tossed and turned in our sleeping bags. Then suddenly, around ten P.M., the radio in our tent crackled to life. I turned on my headlamp, grabbed the walkie–talkie, and listened intently. The voice on the radio was that of Thor Kieser, another American, calling from Camp IV, 1,700 feet above us. “Hey, guys,” Thor blurted out, his voice tense with alarm. “Chantal and Alex aren’t back. I don’t know where they are.”

I sighed in pure frustration. In the beam of my headlamp, I saw a kindred expression on Scott’s face. Without exchanging a word, we knew what this meant. Our summit push was now on indefinite hold. Instead of moving up to Camp IV to get into position, the next day we would find ourselves caught up in a search—and possibly a rescue. The jinx was alive and well.

On August 3, as Scott and I had made the long haul from base camp up to Camp III (a grueling 7,000 feet of altitude gain), Thor Kieser, Chantal Mauduit, and Aleksei Nikiforov had gone for the summit from Camp IV. Chantal, a very ambitious French alpinist, had originally been part of a Swiss team independent from ours. When all of her partners had thrown in the towel on the mountain and left for home, she had stayed on (illegally, in terms of the permit system) and in effect grafted herself onto our group. She was now the only woman on the mountain. Aleksei—or Alex, as we called him—was a Ukrainian member of the Russian quintet that made up the core of our team.

That morning, Alex and Thor had set out at five–thirty a.m., Chantal not until seven. These starting times were much later than Scott and I would have been comfortable with, but the threesome had been delayed because of no shortcuts to the top high winds. Remarkably, climbing without bottled oxygen, Chantal caught up with the men and surged past them. Struggling in the thin air, Thor turned back a few hundred feet below the summit, unwilling to get caught out in the dark. Chantal summited at five p.m., becoming only the fourth woman ever to climb K2. Alex topped out only after dark, at seven p.m.

The proverbial two p.m. turn-around time isn’t an iron–clad rule on K2 (or on Everest, for that matter), but to reach the summit as late as Chantal and Alex did was asking for trouble. And trouble had now arrived.

On the morning of August 4, as Scott and I readied ourselves for the search and/or rescue mission that would cancel our own summit bid, we got another radio call from Thor. The two missing climbers had finally showed up at Camp IV, at seven in the morning, but they were in really bad shape. Chantal had been afraid to push her descent in the night and had bivouacked in the open at 27,500 feet. Three hours later, Alex had found her and talked her into continuing the descent with him—possibly saving her life.

Staggering through the night, the pair had managed to stay on route (no mean feat in the dark, given the confusing topography of K2’s domeshaped summit). But by the time they reached the tents at Camp IV, Chantal was suffering from snow blindness, a painful condition caused by leaving your goggles off for too long, even in cloudy weather. Ultraviolet rays burn the cornea, temporarily robbing you of your vision. Chantal was also utterly exhausted, and she thought she had frostbitten feet. In only marginally better shape, but determined to get down as fast as possible, Alex abandoned Chantal to Thor’s safekeeping and pushed on toward our Camp III. He just said, “Bye-bye” and took off.

Thor himself was close to exhaustion from his previous day’s effort, but on August 4 he gamely set out to shepherd a played–out Chantal down the mountain. It’s an almost impossible and incredibly dangerous task to get a person in that kind of shape down slopes and ridges that are no child’s play for even the freshest climber. Thor had scrounged a ten-foot hank of rope from somewhere—that’s all he had to belay Chantal with, and maybe to rappel.

Over the radio to us, Thor had pleaded, “Hey, you guys, I might need some help to get her down.” So Scott and I had made the only conscionable decision: to go up and help.

As we were getting ready, we watched as Alex haltingly worked his way down the slope above, eventually stumbling toward camp. We went up a short distance to assist him, then helped him get into one of the tents, where we plied and plied him with liquids, since he was severely dehydrated. Meanwhile, surprisingly, he didn’t show any concern for Chantal.

Going to the summit, both he and Chantal had pushed themselves over the edge, driven themselves to their very limits. It happens all the time on the highest mountains, but it’s kind of ridiculous. To make matters worse, on August 4 the snow conditions were atrocious. Same with the weather: zero visibility. Scott and I tried to go, made it up the slope for a couple of hours, then had to turn around and head back to camp. We made plans for another attempt the following day.

We were in radio communication with Thor. He’d started to bring Chantal down to Camp III, but he only got partway. They had to camp right in the middle of a steep slope, almost a bivouac, though Thor had been smart enough to bring a tent with him.

The next day, August 5, Scott and I got up, packed our gear, and started up again, hoping we could meet up with Thor and Chantal and help them back to our camp. At some point, we could see them through the mist and clouds, two little dots above. It was blowing hard, and little spindrift avalanches were coming down the slope we were climbing. Part of it was stuff Thor and Chantal were kicking off from way above, stuff that by the time it got to us was a little bigger. But no really big slides. I’d scrounged a fiftyfoot length of rope, with which Scott and I were tied together, because of the crevasses that riddled the slope.

At one point, Scott was above me. Something just didn’t feel right. I yelled up to Scott, “Wait a minute, this is not a good slope.” It was loaded, ready to avalanche. If you’ve done enough climbing, you can feel the load on a slope. I attribute that sense to the years of guiding I’d done by that point in my life. At that time, Scott hadn’t done as much guiding as I had.

We stopped in our tracks. I said, “Man, let’s not get ourselves killed doing this. Let’s discuss this.” Scott sat down facing out, looking down at me. I figured, if a big spindrift slide comes down now, we’re going to get washed off the face.

I started digging a hole with my ice ax, thinking I might protect myself if a slide came from above. After a few moments, I looked up just in time to see Scott engulfed by a wave of powder. He disappeared from sight. At once I tucked into my hole and anchored myself, lying on top of my ax, the pick dug into the slope. Bracing myself for impact, I thought,

Here it comes.

It got dark; it got quiet. I felt snow wash over my back. The lights literally went out. I hung on and hung on. And then, the avalanche seemed to subside. I thought I’d saved myself. I thought,

Wow, my little trick worked.

But the fact was, Scott had been blindsided. He was tumbling with the snow, getting swept down the face. He hurtled past me, out of control. Scott was a big guy, maybe 225 pounds. I weigh 165.

The rope came tight. Boom! There was no way I could hold both of us. I got yanked out of my hole, like getting yanked out of bed. I knew instantly what had happened. Scott was plummeting down the mountain, with me in tow, connected by what should have been our lifeline. And there were 8,000 vertical feet of cliff below us.

If you’re caught in an avalanche and careening down the slope, there are several ways of trying to save yourself. One of the ways is called a selfarrest. The idea is to get your ice ax underneath your body, lie on it with all your weight, hold on to the head, and try to dig the pick into the slope, like a brake.

I’d learned the self-arrest when I’d started climbing, and as a guide I’d taught it to countless clients. So the instinct was automatic. It ran through my head even as I was getting jerked and pummeled around by the avalanche: “Number one: Never let go of your ax. Number two: Arrest! Arrest! Arrest!” I kept jabbing with the pick of the ax, but the snow beneath me was so dry, the pick just kept slicing through. I’d reach and dig, reach and dig.

Yet I wasn’t frantic. Everything seemed to be happening in slow motion, and it was as if sound had been turned off. We probably fell a couple of self-arrest hundred feet. For whatever reason, Scott couldn’t even begin to perform his own self-arrest.

Then, as I was still desperately attempting to get a purchase in the snow with my ice ax, suddenly I stopped. A few seconds later, just as I expected, the rope came tight again, with a tremendous jolt. But my pick held. With my self-arrest, I’d stopped both of us.

“Scott, are you okay?” I yelled down.

His answer was almost comical. “My nuts are killing me!” he screamed. The leg loops of his waist harness had had the unfortunate effect, when my arrest slammed him to a sudden stop, of jamming his testicles halfway up to his stomach. If that was the first thing Scott had to complain about, I knew that he’d escaped more serious harm.

Yet our roped-together plunge in the avalanche had been a really close call. If it hadn’t been for the fact that two other mountaineers were in desperate straits, there’s no way Scott or I would ever have tried to climb in those conditions.

Meanwhile, somewhere up above, Thor and Chantal still needed our help—more urgently with each passing half hour.

***

In mountaineering, 8,000 meters—26,247 feet—has come to signify a magical barrier. There are only fourteen peaks in the world that exceed that altitude above sea level, all of them in the Himalaya of Nepal and Tibet or the Karakoram of Pakistan. They range from Everest, at 8,850 meters (29,035 feet) down to Shishapangma, at 8,012 meters (26,286 feet).

During what has often been called the golden age of Himalayan mountaineering, the first ascents of all fourteen were accomplished, beginning with the French on Annapurna in 1950 and ending with the Chinese on Shishapangma in 1964. The stamp of the expeditions that waged that fourteen-year campaign was typically massive—with tons of supplies, hundreds of porters and Sherpas, and a dozen or more principal climbers—as well as fiercely nationalistic, as the French, Swiss, Germans, Austrians, Italians, British, Americans, Japanese, and Chinese vied to knock off the prizes. (If any country can be said to have “won” that competition, it would be Austria, whose leading climbers claimed the first ascents of Cho Oyu, Dhaulagiri, Nanga Parbat, and Broad Peak–two more mountains than any other nation’s climbers would bag.)

Given the gear and technique of the day, it was considered cricket to throw all available means into the assault on an 8,000er. There were experts, after all, who doubted that Everest would ever be climbed. So teams strung miles of fixed ropes up the slopes of the highest peaks, allowing those tons of gear to be safely ferried from camp to camp. They bridged crevasses and short cliffs with metal ladders. And they routinely used bottled oxygen to tame the ravages of thin air in the “Death Zone” above 26,000 feet. (It was long assumed that any attempt to climb Everest without supplemental oxygen would prove fatal.)

Only one of the fourteen 8,000ers was climbed on the initial attempt. Remarkably enough, that was Annapurna, the first of all the fourteen to be ascended, thanks to an utterly brilliant effort spearheaded by the Parisian alpinist Maurice Herzog and three Chamonix guides, Louis Lachenal, Lionel Terray, and Gaston Rébuffat. So heroic was the ascent of a single 8,000er considered that each such deed accrued a seemingly limitless fund of national glory. The fiftieth anniversary of the triumph on K2 in 1954 was recently celebrated in Italy with much pomp and circumstance. The first ascent of Everest by the British the year before—news of which arrived in England at the very moment of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation—has been called, with no apparent irony, “the last great day in the British Empire.” Sir Edmund Hillary remains the most famous mountaineer in history. (Alas, his more experienced partner, the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, does not even rank a close second.)

So hard-won were those early successes on the 8,000-meter peaks that only two men—the Austrians Hermann Buhl and Kurt Diemberger—participated in more than a single triumph. At the cost of losing several toes to frostbite, Buhl pushed on to the summit of Nanga Parbat in a now legendary solo ascent in 1953, after all his teammates had faltered. Diemberger topped out on Dhaulagiri in 1960. And the two men joined forces on an admirably light, small-party first ascent of Broad Peak in 1957. Only eighteen days later, Buhl fell to his death on a neighboring peak when a cornice broke beneath his feet. His body has never been found.

By the mid–1970s, the most ambitious Himalayan mountaineers were attempting the 8,000ers by routes that were far more technically difficult than those followed on the first ascents. Difficulty for its own sake became, in fact, the ultimate cachet. Meanwhile, the first ascent lines, while not exactly being reduced to the humdrum status of “trade routes,” were proving less fearsome than the pioneers had found them. By 1975, for instance, thirty-five different climbers, including the first woman, Junko Tabei from Japan, had successfully climbed Everest by the South Col route opened by Hillary and Tenzing.

Copyright © 2007 by Ed Viesturs with David Roberts. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.