1

PALM SUNDAY

It was a chilly Palm Sunday and Essie Belle Johnson did not have a palm. Several of the other kitchenette dwellers in her lodgings had been to church that day and returned with leaves, sheaves and even large sprays of palm straw to stick up in their mirrors or in one corner of the frame of Mama's picture.

"I used to always go to church on Palm Sunday when I were a child," Essie said, "as well as Easter, too."

"I seldom went," said Laura, "and never regular. My mother was too beat out from Saturday night to get me up in time to go to church. My step-pa sold whiskey--you know, I growed up in bootleg days. My schooling came from bathtub likker, with some small change left over sometimes to go to movies, buy Eskimo pies."

"My mama always woke me up on the Sabbath before she went to work," mused Essie. "Her white folks only gave her one Sunday off a month. She'd give me a nickel to put in Sunday school and a dime for church, then leave something in the pot for me to eat when I got back home. In the evening, Mama would go to services by herself and turn out the light and leave me in bed until I got teen-age. Then I went to church at night, too. I loved those songs, 'Precious Lord, Take My Hand.' Oh, but that's pretty! Let's go to church Easter, Laura."

"Which one, Sanctified or Baptist?"

"Where the singing is best," said Essie.

"Sanctified," said Laura. "But you know I ain't got nothing to wear to church. On Easter Sunday I should decorate my headlights proper. Man told me last week, said, 'Woman, you got bubbies like the headlights on a Packard car sticking out like two forty-fours. Stop shooting me in the eyes that way with what you carries in front of you.'" Laura drew herself up proudly.

"An out-of-shape woman can get by with some poor rags. But you got a good figure, Laura. If you didn't put so much money into the bottle, you could get yourself some clothes."

"Girl, hush! Chilly as it is tonight, I had to get a little wine. Being Sunday, I had to pay more for it bootleg. There ought to be some heat in this old rat-hole."

"You could have got yourself a hat with what you paid for that wine."

"

An Easter bonnet with a blue ribbon on it," sang Laura. "Pshaw, child, by this time next Sunday I might have a new hat. Who knows? Maybe my new man will buy me one."

"If he does, it will be mighty near the first time. You one of these women always buying men something, instead of letting them do for you. You sure are crazy about men, Laura."

"One nice thing about being on relief is, it leaves you plenty time to be sweet to your daddy, have him something ready to eat when he comes from work, have your own head combed. I don't see much sense in a woman working, long as the Home Relief mails out checks. Of course, sometimes I has more energy being idle than I know what to do with. Essie, if I could just set on my haunches and be content like you! You don't even want a drink--just set and get fat, and you're happy."

"I ain't all that happy, Laura. I want my daughter with me. I get lonesome. If it wasn't for you dropping in all the time, I'd be more lonesome. Sure glad you're my neighbor, Laura, even if I can't keep you company with no bottle."

"A few swallows of this and you'd forget about being lonesome. You ought to learn to drink a little, Essie."

"I hate that old raw wine, Laura. It makes me sick at the stomach."

"Your life is empty and your belly, too. You ought to do something. At least, get yourself a man, girl, somebody, anybody."

"A man?" cried Essie. "No! Not to beat me all over the head. I'm cranky. I'm getting set in my ways. And I been long disgusted with men, low-down, no-good as they are."

"Well, smoke a reefer then. Try a little goopher dust. Dope, nope? Live out your life, instead of just setting here gathering pounds. Excite yourself, get high and fly."

"Somehow I kinder like to keep my head clear. Even if I am beat, I like to know it."

"Woman, you sound right simple," declared Laura.

"Anyhow, where would I get the money for them bad habits you're talking about, even if I wanted them?"

"The Lord helps them that helps themselves," declared Laura, shaking the last drop of sherry out of her pint bottle and laying it flat on the porcelain table. "Essie, don't you want no kind of pleasure out of living? You ain't that old. You still got breasts, legs, and what God give you. No fun, you might as well die."

"Sometimes I think so, rooming all by myself like this and living off the Welfare. About all I can do nowadays is ask the Lord to take my hand."

"Well, why don't you do that then? Get holy, sanctify yourself. The Lord is no respecter of persons if He takes a pimp's hand and makes a bishop out of him, like he did with Bishop Longjohn over there on Lenox Avenue. That saint had three whores on the block ten years ago. He's got a better racket now, the Gospel! And a rock and roll band out of this world in front of the pulpit with a piano player that beats Teddy Wilson. That bishop's found himself a great shill."

"Shill?"

"Racket, girl, racket."

"Religion don't just have to be a racket, Laura, do it? Maybe he's converted."

"Converted about as much as an atom bomb is converted to peace."

"Longjohn might be converted, Laura."

"All the money he takes in every Sunday would convert me," declared Laura. "Money! I sure wish I had some. Say, Essie, why don't you and me start a church like Mother Bradley's? We ain't doing nothing else useful, and it would beat Home Relief. You sing good. I'll preach. We'll both take up collection and split it."

"What denomination we gonna be?" asked Essie, amused at the idea.

"Start our own denomination, then we won't be beholding to nobody else," said Laura.

"Where we gonna start it?" asked Essie.

"Summer's coming, ain't it? We'll start it on the street where the bishop started his, right outdoors this summer, rent free, on the corner."

Essie grinned. "You mean, in the gutter where we are."

"On the curb above the gutter, girl. We'll save them lower down than us."

"Now, who could they be?"

"The ones who can do what you can't do, drink without getting sick, stay high on Sneaky Pete wine. Gamble away their rent. Play up their relief check on the numbers. Lay with each other without getting disgusted, no matter how many unwanted kids they produce. Use the needle, support the dope trade. Them's the ones we'll set out to convert."

"With what?"

"With Jesus. He comes free," cried Laura. "Girl, you know I think I hit upon an idea. Just ask Jesus to take your hand, in public, Essie. Then, next thing you know, somebody will think He's got your hand, and will put some cash in yours to see if they can make the same contact. Folks is simple. Money they're going to throw away anyhow, so they might as well throw some our way. Just walk with God, and tell the rest of them to follow you, and

pay as they go. Dig?"

Taking it like an impossible game, Essie murmured, "Um-hum!" But Laura already saw herself as a lady preacher. Besides, the wine was gone. In her new role, she felt like singing, and she did.

"Precious Lord, take my hand,

Lead me on, let me stand.

I am weak, I am tired, I am worn."She had a strange voice, deep, strong, wine-rusty, and wild.

"Through the storms of the night

Lead me on to the light.

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me on."Essie was moved. "I knowed you could sing blues, Laura, but I never knowed you knew them kind of songs before."

"Pick it up with me," said Laura. "Pick it up, girl."

Cooler, higher and sweeter than Laura's, Essie's voice picked up the song, and the drab cold kitchenette room filled with melody was no longer cold, no longer drab. Even the light seemed brighter.

"When my way grows drear,

Precious Lord, linger near.

When the day is almost gone,

Hear my cry, hear my call,

Guide my feet lest I fall.

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me on.""Essie, if I could sing like you, I'd be Mahalia Jackson," cried Laura. "You're a songster!"

"Mahalia is a good woman. I ain't," said Essie.

"To make her money, records and all, I'd be willing to be good myself," said Laura.

"It ain't easy to get hold of money. I've tried, Lord knows I've tried to get ahead. Ever since I come up North I been scuffling to get enough money to send for my daughter and get a little two-, three-room apartment for her and me to stay in."

"Pshaw! For love nor money can't nobody get no apartment in Harlem, unless you got enough money to pay under the table."

"Marietta's sixteen and ain't been with me, her mama, not two years hand-running since she were born. I always wanted that child with me. Never had her. Laura, I was borned to bad luck."

"Essie, it's because you don't use your talents, that's why," said Laura, looking at her portly friend with a critical eye. "All you use, like most women, is the what-you-may-call-it that you sets on, your assets instead of your head. Now, me, I got a brain, but I pay it no mind. I hope you will, though, and listen to my advice. Girl, with your voice, raise your fat disgusted self up out of that relief chair and let's we go make our fortune saving souls.

"Remember Elder Becton? Remember that white woman back in depression days, Aimee Semple McPherson, what put herself on some wings and opened up a temple and made a million dollars? Girl, we'll call ourselves sisters, use my name, the Reed Sisters. Even if we ain't no relation, we're sisters in God. You sing, I'll preach. We'll stand on the curb and let the sinners in the gutter come to us. You know, my grandpa down in North Carolina was a jackleg preacher. And when I get full of wine, I can whoop and holler real good. Listen to this spiel."

Laura jumped up from her chair with gestures. "I'll tell them Lenox Avenue sinners," she said, "you-all better come to Jesus! Yes, sinning like hell every night, you better, because the atom bomb's about to destroy this world, and you ain't ready! Get ready! Get ready! I say, aw, let Him take your hand. Yes, sisters, brothers, He's got mine! Let Him take yours and walk with Him. Now, sing with me:

"When the darkness appears,

Precious Lord, linger near.

When my life is almost gone,

At the river I stand,

Guide my feet, hold my hand.

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me on.

"Grab the chorus, Essie. Sing it, girl, sing!"

Essie's voice rose full and persuasive, so persuasive, in fact, that melodically she persuaded herself and Laura, too, that they ought to go out into the streets and move multitudes.

"I sure wish I had me some more wine," sighed Laura when they had finished singing.

"The Wine of God is all we need," Essie said. "Laura, I'm gonna pray." She knelt down with her arms on the chair where she had been sitting. "Lord, I wish you would take my hand. Lead me on, show me the way, help me to be good. Help Sister Laura, too. And help us both to help others to be good. That I wish in my heart, Lord, I do."

"Amen!" cried Laura with her hand on her empty glass.

" 'Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life,' " murmured Essie.

"And never catch up with you unless you get up and do something yourself," said Laura.

2

BLUE MONDAY

The next morning, which was a blue Monday, when Laura could hardly scrape together enough change to combinate a number and put a dime on the lead, Essie said as she washed the percolator top, "I prayed again this morning for what we was talking about last night."

Laura, who had left her bed unmade down the hall in Number 7 to tap on Essie's door in the hope of a hot cup of coffee, looked puzzled. "What?"

"That church we gonna start," said Essie. "I believe God answers prayer. In fact, that church is started."

"Started? Where?"

"Right here in this room with you and me."

"Then lemme pass the collection plate," said Laura, "because I dreamed about fish last night--782--and that is a good number to play. Here, put some change in this saucer, and I'll put the number in for you, too."

"I said I was

praying, Laura, not playing. If we're gonna save souls, have I got to save you from sin first?"

"Oh, you talking about starting a church?" said Laura, her mind clearing of sleep a little. "Well, as soon as the weather warms up a bit, we'll buy a Bible and a tambourine and plant our feet on the rock of 126th and Lenox and start. But right now, I want me at least forty-five cents to work on these numbers. Suppose

fish jumps out today? If it did, and I didn't catch it, I sure would be mad. Girl, pour me one little drop more of that coffee. If I could just find that old Negro who's liking me so much, so he says, I might could maybe get a dollar or two. But he never does come by here on Monday."

"Laura, you oughtn't to be encouraging that married man to be laying up with you."

"He encourages his self," yawned Laura. "Can I help it if I appeal to him whenever he can get out of his wife's sight? The Lord give me my smooth brown body, girl, and I ain't one to let it go to waste. Excuse me, I'm gonna comb my hair and go downstairs and put these numbers in. A small hit's better than none. But I sure hate to be so poor! Maybe that Chinese that winked at me from behind the lunch counter will feel in a lending mood this morning."

"A Christian woman taking up with a heathen," said Essie.

"On a blue Monday morning I would take up with a dog," said Laura, "if the dog said, 'Baby, how about a drink?' Soon as this coffee dies down, I'm gonna need something a little stronger."

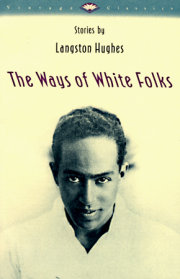

Copyright © 2006 by Langston Hughes. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.