The Guy Next DoorHenry AlfordI’ve never killed anyone before. But I once felt like I had. This man and I did not, at first blush, have much in common. I was a pot–smoking, Joni Mitchell—listening thirty–one–year–old gay man; he was a profane, eighty–year–old former longshoreman named John Maguire whose nickname was Mugsy. In the two years that I’d been living in the apartment contiguous to his, we’d never shared more words than the occasional grunt–based hello in the hallway.

And then I made the phone call that changed both our lives.

“Mr. Maguire?”

“Yeah.” His voice was brusque and Bronxy.

“It’s Henry Alford. I live across the hall in 4E?”

“Uh–huh.”

“Do you know about the auction being held on Friday? For the three apartments in the building, including yours?”

“No. I’m not a member of the co–op board, so they don’t tell me anything.”

“Your landlord, Mr. Z——, is about $13,000 in arrears,” I explained. “So the co–op board is holding a public auction of his three apartments on Friday. You and the other tenants have what are known as statutory rights, so you can’t be kicked out and the rent can’t be raised no matter who owns the apartments."

“I know all about it. I’ve been down to the attorney general’s office.”

“Good, so you know your rights,” I said, a small amount of relief helping to bolster my mounting anxiety about my next statement. “Well, anyway, I’m thinking about, uh, making a bid on your apartment.”

As soon as the words came out of my mouth, I wanted to soften or reshape them. It was no secret that John had had two heart attacks. I added, “As a, as a—as a sort of long–term investment, of course.”

“You can do what you want.”

“Great. But I’ve never been in your apartment, and I wonder if I could look at it sometime.” The evening before, I’d walked out on our mutual fire escape and tried to peek in through his windows, to no avail.

“Okay,” he said.

“Well, I was wondering if I could look at it, say, right now.”

“Let me put my pants on,” he said, and hung up the phone.

About ninety seconds later, I heard John open his door and then knock softly on mine—an act that requires merely leaning forward, as the two doors are thirty–five inches apart. I greeted him and shut the door behind me. A wiry and fastidious man, John projected equal amounts of boyishness and scowling, a sour angel. I stood stone–still in his doorway, cowed. Although in the weeks previous the prospect of inexpensively doubling the size of my apartment had filled me with a sensation that I can only describe as tingly, that tingle now fled me. No, this was not the wonderfully grabby, slightly narcissistic feeling that looking at real estate usually engenders—the one where empty rooms symbolize solutions to your problems, the one where hobbies get their own dedicated spaces and children get their own bedrooms and novels gush from printers like lobsters from an aquarium during a Mob hit. This was much more like an IRS audit.

“Come on,” John said, waving me into the living room.

We grimly and quickly toured the premises. His apartment, I could see, was almost identical to mine. We both had six hundred railroad-style square feet overlooking a lovely, tree–shaded street in Greenwich Village; each was worth about $130,000, a price that would have been higher were the apartments not fourth–floor walk–ups. John’s place was immaculate. It had a sweet, slightly soapy smell.

“I’m surprised it took the co–op board so long to catch on to Mr. Z——,” John said when we’d returned to the kitchen. “He’s no good and he’ll never be good! He has the building next door, too. You ever been in there? It’s a dump!"

“I’ve never been in there.”

“It’s a dump!”

I thanked John for the tour and left.

Two days later, I realized I’d forgotten to ask him an important question, so I called again. I asked him how he was doing, and he said, “Alrighty.”

“Uh, some of the people who are bidding on your apartment are wondering what you’re paying for rent,” I said. “Would you be uncomfortable…”

“It’s $81.23.”

“Eighty-one twenty-three a month?” I asked, surprised it was this low. The maintenance on the apartment was $332 a month, so a rent of $81.23 meant that whoever bought the apartment would be $250.77 out of pocket a month.

“That’s right. Anybody buying this is gonna get stuck.”

“Right,” I said, laughing nervously. “How long have you been living there?”

“Fifty years.”

“Wow. You’re a…"

“I’m a fixture. I’m a goddamn fixture.”

I needed to figure out how much to wager at the auction, so that night I sat down and did the actuarial work. Two hundred and fifty dollars and seventy–seven cents a month was about $3,000 a year. So if John lived another five years, I’d be spending $15,000. If he lived ten years, I’d be spending $30,000. If he lived twenty years, I’d be spending $60,000.

I decided twenty years was a good, conservative figure to work with; after all, it wasn’t as if John were some female goatherd in the Urals subsisting on a diet of yogurt. Subtracting $60,000 from the apartment’s $130,000 value left me with $70,000. Then I subtracted another $25,000 for cost–of–living increases and the hassle of being your next door neighbor's landlord. That left $45,000. That was my ceiling for bidding.

The auction took place a few days later. The setup was much more casual than I’d imagined: a spindly, middle–aged auctioneer stood at a card table he'd set up under the rotunda of the Supreme Court of the State of New York; four of us bidders and our companions huddled round, clutching our checkbooks. Office workers and other passersby drifted past us, unmindful of the tiny acts of manifest destiny taking place just feet away.

Each of the three apartments underwent a short volley of bidding. Because the apartments were being sold with rights-bearing tenants in them, and because there was no formal process by which potential buyers not living in the building could meet or learn the age and medical status of these tenants, the auction attracted only one outside speculator. In the end, all three apartments were bought by people already living in the building.

I felt like I was taking part in insider trading—a dark, sweet, criminal feeling made only more so when I got the apartment for $17,000.

When I saw John in the hallway the next day, I told him that I’d bought his apartment. His face betrayed no reaction. We agreed that he would slip his rent check under my door the first of each month. John explained that Mr. Z—— had four of his rent checks that he hadn't cashed. John said, "Oh, he's no good. He's a louse." The part of my brain that I had been labeling “I Am a Yuppie Interloper” was slightly relieved by this statement; I knew I’d be a better landlord than Mr. Z——.

But the following day as I was leaving the building, I ran into a fellow resident I’ll call Tina. Tina said she’d heard about the auction, and was glad that Teresa in 2E and I had been able to buy our own apartments, but was dismayed that Jere in 1E had bought Mrs. Englehardt's apartment, because now Jere—a building developer by trade—would be waiting for the frail, ninety–something Mrs. Englehardt “to drop dead.”

I corrected Tina, telling her that I had not bought my own apartment—I’d bought John’s. She laughed nervously.

Eager to undercut the awkwardness, I started rambling, telling Tina that I didn't know much about John and asking her if he’d ever been married. She said he hadn't. She said the only family she was aware of was a brother who lived in the city.

Later that night, I ran into Tina again, this time in the vestibule of the building. She was picking up a brass doorknob that had fallen off the inside door. “If we get new brass knobs, I’m gonna keep the old ones and hit Jere over the head with them,” she told me, referring to the man who was waiting for the old woman to drop dead. “I’m not kidding: he better watch it.”

I wondered if I should, too.

But to my friends, the fact that I'd bought an apartment that housed a man who’d had two heart attacks was the stuff of comedy. More than once did I hear the line “Getting enough heavy cream in your coffee, Mugsy?”

My early days of landlordship were marked by a certain suspensefulness. One afternoon about a month after the auction, I heard a beeping sound in the hallway; the battery of our floor's smoke alarm was dying. Not having the right size to replace it with, I decided simply to take the smoke detector down, bring it into my apartment, and remove the dying battery.

When I awoke the next morning and saw the smoke detector on my kitchen table, I got a chill. What if John had died in the night and the cops had found the smoke detector in my apartment. That wouldn't have looked too good for me.

But the biggest change that resulted from buying John’s apartment was that I became much more conscious of the fact that if the space between our doors was only thirty–five inches, the walls between us weren’t even five inches. I heard John through these walls far more frequently than I had in the past. Usually these sounds were unidentifiable bumps or scrapes, but sometimes they were John muttering or yelling to himself. I knew that John liked a drop of whiskey from time to time, and sometimes in the evening, presumably after some liquid refreshment, he would sing softly. One muffled ditty I heard repeatedly sounded like:

Someone runner sleef Angola.

Doctor leaving town his molar.

She was gentle from I lingered.

Now he is a big brown cow.More mindful now of John’s existence, I suddenly realized that, like me, he almost never had anyone to his apartment. His one friend was a lady named Loretta, who, accompanied by her yippy little shih tzu, would sidle up to the intercom at our building's entrance, buzz John, and then broadcast screamingly loud conversations with him.

“John!” I heard her yell one afternoon. “I have some meat for you!”

“What?!”

“MEAT!”

“Okay.”

“Come and get it. I’m not coming up.”

“For what?”

“The meat! I have meat!”

I could sense that there was a lot of love in this relationship, but I could also sense that this love had congealed or hardened over the years, perhaps as a result of a misunderstanding or a too–long car trip.

The chief noise by which John and I could detect each other’s presence was the opening and closing of our front doors. If I was getting ready to go outside and suddenly heard John’s door open, I would sometimes wait thirty seconds so I wouldn't have to talk to him in the hallway; this landlord figured that the more relaxed my tenant felt around me, the more he might start lodging complaints about his heating or plumbing.

But actually John had very few gripes at the beginning, and our encounters in the hallway were mostly charmed. One day, trailing him down the stairs by a floor, I saw him suddenly reverse direction and come back up the stairs. Just as he passed me, he smiled tightly and said, “Forgot my teeth.”

We weren’t sure, though, whether to acknowledge each other when we passed on the street. The first three or four times, we betrayed no recognition of each other. Then, one balmy August afternoon, I saw him—turned out in his usual plaid pants, porkpie hat, and cardigan sweater, with a rolled-up

New York Post under his arm—walking Loretta’s dog down West Fourth Street. Sensing an easy opportunity for conversation, I walked over to them. Beholding the dog’s pink barrette and rhinestone–studded collar, I asked John what her name was. He looked down at the sidewalk in embarrassment and told me: “Muffin.”

About five months after the auction, water from the apartment above John's started dripping through his bathroom ceiling. John was incensed. He knocked on my door one afternoon and hustled me over to his apartment to show me how the rust-colored water was oozing into his bathroom lighting fixture; in showing it to me, he called Roberta, the woman upstairs, “that bitch” four times.

“Thirty–seven years I’m living here, and nothing like this ever happened to me!” he said. I realized then that when he'd told me before that he’d been living in the building for fifty years, he’d probably been trying to scare me off. I called Roberta, who promised to fix the leak. All seemed well until the following week, when it started again and John called her at 4:00 a.m. and yelled at her.

“John, you should probably let me handle those kinds of calls,” I told him.

“I can talk for myself!”

“Right. But calling at 4:00 a.m.?”

“That bitch is gonna electrocute me!”

I apologized to him and promised to get a handyman in; John thanked me.

Time passed. John’s next problem was a much less troublesome one concerning his bathtub, whose handles leaked water. This time, softly knocking on my door with a knock that was as much a scratch as a knock, he asked me to come over and take a look. I went. As I stood in his tiny kitchen, John smiled and reached for my right hand; holding it, he guided me into the bathroom. I watched, my hand still in his, as he turned on the water and showed me how it burbled through the handles.

There was absolutely nothing sexual about the way John touched me, and yet I was surprised he’d do it because I was fairly certain that he knew I was gay. No, the hand–holding felt avuncular. And, somehow, like something more, too. I imagined that John knew how few people there were in my life, so maybe the hand–holding was like a concentrated dose of friendliness, a kind of bodily hello meant to rebuff our mutual isolation. That we hadn’t exactly paved the way to this moment didn't seem to matter. Sometimes you reach into the dark and hold the hand you find there.

I noticed something with the bathtub leak, as well as with a subsequent leak from the kitchen sink: I actually enjoyed dealing with these problems on John's behalf. It had started when I followed him up the four flights of stairs one day. John, out of breath, stopped and told me to pass him. “These stairs are getting to be too much for me,” he said. Uncertain how to react to the rawness of this confession, I wondered if John was hinting that he'd like me to try to buy him out of his apartment. But then remembering that he’d once told me, “I'm not going anywhere,” I rejected this idea. “Yeah, they're getting to me, too,” I said.

Seconds later I entered my apartment feeling like an asshole for having been so glib; the man, after all, had had two heart attacks. The only antidote, I quickly decided, was to take action. I called a plumber to look at John’s kitchen sink leak, as I had promised to do three days earlier.

I needed to make a cake for a friend’s birthday that day, so while I waited for the plumber to come, I pulled out some supplies and started baking. Just as I began whipping some eggs, it occurred to me that having the power—and, yes, perhaps the money—to bring a plumber–shaped ray of sunshine into John’s life felt really good. Maybe I didn’t HAVE to be an evil yuppie who relished the sight of his neighbor's deterioration, abetting it by letting the leak from a kitchen sink turn into a juggernaut of Chinese water torture. I could be something else—a take–charge relief worker; Mother Hale with a whisk.

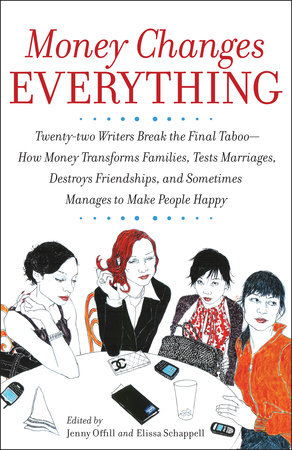

Copyright © 2007 by Jenny Offill. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.