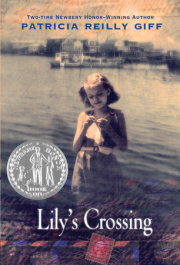

chapter one

bird

Bird clattered down the stairs in back of Mama, past Mrs. Daley’s on the first floor, and Sullivan the baker at the window in front. Outside she and Mama held hands, swinging them back and forth as they hurried along Water Street.

“Hot.” Bird squinted up at the sun that beat down, huge and orange.

“Even this early,” Mama agreed.

For a quick moment, they stopped to look at the tower standing by itself at the edge of the East River. One day it would be part of a great bridge.

What would it be like to stand on top, arms out, seeing the world the way a bird would? she wondered.

Bird, her nickname.

She pulled her heavy hair off her neck. “Mrs. Daley says they’ll never be able to finish that bridge. She says it will collapse under its own weight and tumble right into the river.”

They said it together, laughing: “Mrs. Daley says more than her prayers.”

“Still,” Bird said, “half of Brooklyn says the same thing.”

“Not I,” Mama said, “and not your da. We know anything is possible, otherwise we’d still be in the Old Country scrabbling for a bit of food.”

Bird glanced at Mama, the freckles on her nose, her hair with a few strands of gray coming out of her bun ten minutes after she’d looped it up: Mama’s strong face, which Da always said was just like Bird’s. She couldn’t see that. When she looked in the mirror, she saw the freckles, the gray eyes, and the straight nose, but altogether it didn’t add up to Mama’s face.

She was glad to reach the house on the corner, the number 112 painted over the door, and the vestibule out of the sun.

They climbed the stairs, the light dim as they stopped to catch their breath on each landing. “Let me.” Bird took the blue cloth medicine bag that hung over Mama’s shoulder. “It seems your patients are always on the top floor.”

“Ah, isn’t it so,” Mama said, holding her side. “And the babies always coming in the dead cold of winter, or on steamy days like this.”

Bird could feel the tick of excitement. Mama’s words to her were deep inside her head: “Only days until your thirteenth birthday. You’re old enough to come with me for a birthing.” Bird’s feet tapped it out on the steps: a baby, a baby.

She’d been helping Mama for a long time, chopping her healing herbs and drying them, helping to wash old Mrs. Cunningham, bringing tonic to Mr. Harris. But this! A baby coming! She couldn’t have been more excited.

On the fifth floor, the door was half-open. Two children played under a window; an old man rocked in the one chair, a toddler on his lap pulling at his beard. “The daughter’s inside,” he said.

In the bedroom, the daughter lay in a nest of blankets, her head turned away, her hair in long dark strands over the covers. She made a deep sound in her throat, then turned toward them, and Bird could see how glad she was that Mama was there.

Who wouldn’t be glad to see Mama, who knew all about healing, about birthing? Mama, who always made things turn out right.

Mama patted the woman’s arm. “I know, Mrs. Taylor.” She nodded at Bird. “Now here’s what you’ll do. You’ll sit on the other side of the bed there. Hold her hand, and cool her forehead with a damp cloth.”

Easy enough, Bird thought.

“And I’ll have the work of it,” the woman said before another pain caught her, blanching the color from her cheeks.

“You’ve done it all before.” Mama leaned over to open her bag. “After three girls, there’s nothing to the fourth, is there now?”

Mama made a tent of the blankets so she could help with the birth, and Bird went into the other room to fill a pan with water and wring out a rag. She stepped over the children as she went, bending down to touch the tops of their heads.

Back in the bedroom she ran the rag over the woman’s neck and face. She held her hand during the pains for as long as she could stand it, then pulled her own hand away in between each one. Bird’s hands were larger than Mama’s already, but still she felt as if her fingers were being crushed in the woman’s grip.

At first the woman talked a little, telling them that her husband wanted a boy, that he wouldn’t forgive her if it was another girl, but after a while it was only her breathing Bird heard in that stifling room, and sometimes that sound in her throat, but Mama’s voice was sure and soft, telling her it wouldn’t be long.

Bird sat there thinking about the miracle of it, to be like Mama, to be able to do this. She wanted nothing more than that, to go up and down the streets of Brooklyn, with all that Mama knew in her head, the herbs to cure in a bag looped over her arm, the babies to birth. Bird watched Mama wipe her own forehead with her sleeve, then put her hands on the woman, pressing down and murmuring, “Take another breath, and as you let it out, push with me, push.”

It went on and on, and the room was filled with that July heat, with air that never moved. Such a long day, and the sounds the woman made were much louder now, so loud that the two children came to the door, staring in, until Mama realized they were there. She reached with her foot to push the door and gently closed them out.

And then the smell of blood was in the room, and the baby slid into Mama’s hands, wet and glistening. “A girl.” She handed her to Bird.

Too bad about the foolish husband, Bird thought, looking down at the baby, who was pale, and tiny, and crying weakly. “Beautiful,” she breathed, then washed her with water from the pan and wrapped her in the receiving blanket Mama took from her bag.

Bird could feel the wetness in her eyes from the won- der of it, and the woman sighed and asked, “What’s your name?”

“Bridget Mallon.” The name sounded strange; no one called her anything but Bird.

“Bridget,” the woman said. “Then that will be her middle name. Mary Bridget.”

Copyright © 2006 by Patricia Reilly Giff. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.