Chapter One

SOME QUALITY in my father’s voice always changed when he spoke of my uncles—the one who’d been incarcerated in a federal prison in the Second World War, and the one who’d given a year of his life at that time to alternate service. I don’t remember now how or even whether my father explained their choices to me, or how I came to know what those choices were; but long before I understood any of that, I understood by the shift in my father’s voice how much he admired them. I understood that he believed they’d done the right thing, the hard thing.

They were conscientious objectors, my uncles, in a war that was seen as “good” and “just”—though they made their stand even before America entered that war, when they were required to register for the draft in 1940, the first peacetime draft in the nation’s history. Both of my uncles felt that even in a just war—perhaps especially in a just war— men should follow their conscience. Like my father, both were radical Christians. They believed that the Jesus who conceived of human life as having the potential for moral goodness was speaking of a necessary action to be taken when he called on his followers to love their enemies, to pray for those who persecuted them, to turn the other cheek to those who struck them.

And so my uncles acted. One of them refused to acknowledge that the state might have the right to command him to kill another human being and didn’t register at all; he was the one who went to jail. The other registered but asked to be exempted from that command on religious grounds and was given alternative service.

For years I didn’t think to question my father about his own choices during World War Two. I suppose I assumed, on those rare occasions when it might have occurred to me to think about it at all, that he had escaped the issue somehow because of having children—my older brother was born in August of 1941. I’m not sure when I learned he’d taken the exemption available to him as an ordained minister, or whether that too was just an assumption, accurate in this case. At any rate, it is what I finally assumed. And then further assumed that the tone of awe and admiration that rose in his voice for my uncles, and for his other pacifist friends who did what my uncles did, rose because he admired their greater courage, their greater conviction than his own. Certainly he never said anything that would have led me to think anything else.

After his death, though, I was sorting through the few papers he’d left behind and I came upon a letter that called up for question all of my assumptions. It was addressed to my father in October of 1940, and it was from another young man, also a minister, someone who must have believed—as, it became clear, my father had too—that when Christ spoke of loving your enemies, he was asking for something rather specific from you.

The letter said:

Dear Mr. Nichols: It was a great joy to learn that I am not the only person in this part of the country who has decided that there can be absolutely no compromise with conscription. Notice of your refusal to register and a copy of your statement to the registration board reached me by way of a clipping from the Dispatch sent by my parents in St. Paul.

The young man went on to ask about my father’s family’s attitude toward his position, to speak of the support he had from his family, to inquire about what the repercussions had been from my father’s employer, and ended:

More strength to you in your stand. Sincerely yours, Rev. Winslow Wilson.

I was stunned, reading this. Everything I’d understood about my father’s behavior at that time had been simply wrong. He had refused, my father! He had, in fact, taken the most extreme course possible in resisting and because of this had become, momentarily, a public person, written up in the St. Paul Dispatch. My father, modest, shy as he was, had made a difficult, unpopular, public stand.

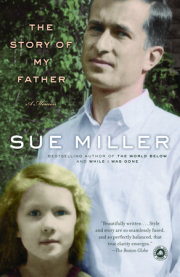

And suddenly it seemed utterly right to me that resistance had been his wish, his intention. It made a kind of emotional sense that caused me to feel, instantly, how little sense my earlier more or less unframed assumptions had made. Of course! I thought. And with that thought it was as though my father stepped forward to meet me as he had been in 1940: twenty-five years old, newly married, teaching literature and history and religion at his first real job, as an assistant professor at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. That stage of his life—and he in it—had always been indistinct to me, as the lives of parents before their children exist always are to those children; but now, holding this letter in my hands, I remembered anew and vividly the numerous photographs in our family albums of him then—a slender young man, intense-looking and handsome, with a shock of dark hair swept back from his high forehead. A radical young man, it would seem. More radical in many ways than my own son was now. A young man ready, perhaps even eager, to embrace the fate his powerful beliefs were calling him to. Sitting there, I felt a rush of love and pity for him in his youth, in his passionate convictions—really, the same feeling I often had for my son when he argued his heartfelt positions. Abruptly, they seemed alike to me and equally dear: my father, my son. I felt as though my father had been waiting for this moment to be born to me as the young man he’d been, so touchingly willing to bear witness to his conscience; and the surprise of this new sense of him, this birth, was a gift to me, a sudden balm in those days of my most intense grief.

But what had called him back? What made him turn away from his choice?—which would have been hard, of course, but satisfying too, in the way that acting on our deepest feelings and commitments is always satisfying. What made him take the easier path, the one that kept him safe, home, out of prison—the exemption—but the path that also denied him the satisfaction of acting on his beliefs, that pride of bearing witness?

He’d kept another letter in the envelope with the one from the young Reverend Wilson, and this one I can’t quote from; it angered me so much that I threw it away after reading it. It was written a few months after Winslow Wilson’s, and it was from my grandfather, my mother’s father. It counseled my father against taking the path that beckoned him. As part of its argument, it pointed to my mother’s pregnancy—which she must just have discovered—and it suggested, terribly delicately, a kind of vulnerability, perhaps even a slight . . . instability . . . on her part, to which my father would be abandoning her and their child if he were imprisoned. Of course, the letter said, if my father truly felt this was the right thing to do, to ask my mother to manage this difficult situation, he and my grandmother (they lived nearby; he was the pastor of a large and prominent Minneapolis church) would do all they could to provide the support she would need in my father’s absence.

There was more. My grandfather called up the contract my father would be breaking with the college, the responsibilities he’d undertaken there that he would be abandoning; but again he affirmed his support, “of course,” if my father felt this was the right thing to do.

For fifty years my father had kept these two letters together, the one that embraced him in his decision and confirmed his choice to make his life a kind of witness to his faith and beliefs, and the other, which cautioned against it. And during all those years he’d spoken not a word of regret, of bitterness or sorrow, for the choice he’d made in the end. He’d never even made an accounting of that choice in my presence—as if in making his decision he’d lost forever the right to speak of the beliefs he hadn’t acted on.

I was sitting in my own sunny living room in Boston when I read these letters. I stayed there for a while, staring out at the red-brick church across the street, thinking about this new sense of my father and welcoming it. And then I remembered, I realized, that I in fact did have a written explanation he’d made of himself and of his choice.

I went up to my study and scrambled through my files of family papers until I found it. It was a homily my father had given at my older brother’s wedding. This is it, in its entirety:

There is a certain similarity between marriage and the Christian religion, which is suggested by the text in our gospel reading: “Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you.”

The dominant note at the beginning of marriage is the joy of mutual possessing, of a “choosing” triumphantly accomplished. And this is as it should be.

So in religion there is at the beginning often a searching and a choosing, an affirming of that good which one may serve with conviction. And this too is as it should be. But in time we see more. We become aware that our seeking and our choosing is not so self-determined as we had thought, but our response to a Seeker who had already found us. We come to understand that text: “Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you.”

So with marriage we understand more in time. Deeper than the joy of a “choosing” triumphantly fulfilled is the awareness of a need to be met, of a claim acknowledged. Few things are as potent to give meaning to life as the sense of answering a need and fulfilling a responsibility which no one else can meet.

It is wonderful indeed that we can choose and achieve our choice, but still more wonderful that we are chosen.

Reading the homily in this new context made it more moving to me than it had been the first times I’d read it. And like the revelation that my father would have chosen to resist conscription, it seemed suddenly right to me, more deeply right than before. It made me understand him. My father, a young impassioned man, had chosen twice, and twice he’d chosen in joy and triumph—his faith and my mother. And then it turned out that each of those two choices presented the “claim” to be “acknowledged” he spoke of in the homily. Further, it turned out that those claims, as construed by my grandfather and—I must assume—as accepted in that construction by my father, conflicted. My father had to find a way to reconcile them or to decide which claim took precedence. In the event, he honored the personal claim, the smaller, more private one, and never spoke of the decision again.

My older brother’s wedding, for which the homily was written, took place in 1968. Sixteen years later, when I was to be married for the second time, I asked my father to preside as minister at the ceremony; and, having checked with my brother and sister-in-law first, I asked him to read the same homily he’d read at their wedding, which I’d found so moving even without yet understanding its fullest implications in my father’s life.

My father said yes. But when the moment came for that part of the service, something seemed to go wrong in him. He held the paper in front of him, but he didn’t seem to be able to read it. I tried to indicate to him that it was all right—I leaned forward, I think I touched his arm. After a moment, his voice shaking, he spoke a few improvised words in place of the homily and then pronounced his blessing on us.

Copyright © 2007 by Sue Miller. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.