1

"Sale Boche"

Even as an old man wearing a sweat suit and sitting in his favorite chair at home in Worcester, Cousy engages in conversation with intensity. He wouldn't be Bob Cousy otherwise. He laughs. He cries. He is alternately introspective, wry, philosophical, eloquent, at times snarky, and, on days when he feels an old man's aches and burdens, crotchety. He likes the attention, the intellectual stimulation. He talks about politics, the past, Kennedy and Trump, George Mikan and Kevin Durant, the latest book he's reading. One conversation ends for a sensible reason: "It's time," Cousy says, brows arched, "for my one o'clock fruit." His old stories roll like the mighty waters, and to him those waters are mighty familiar. He's been telling some of these stories for fifty years. He's refined his lines and pauses. He's played the part of Bob Cousy for so long that he has mastered it. Now, though, it seems he has an additional, higher purpose: He is piecing together his life and assigning a sense of order and context. He's earnestly attempting to understand how the world given to him helped shape the world he made. But when the topic shifts to his parents, and the tension that roiled their marriage when he was only a boy, it's as if the mighty waters evaporate and suddenly he is bound for a darker, more somber place. Conversationally, he's in unfamiliar territory. No stories come by rote. The pauses are longer and more numerous. He explains haltingly how his mother sometimes lashed out at his father and struck him. Suddenly his face draws tight. It's as if he is seeing her strike his father again, the scene running through his mind on grainy celluloid. Another pause: lengthy, uncomfortable. Finally, thinking of his father, he says, "He just sat there and took it." Cousy stares across his living room, across time.

In the glory of his time with the Boston Celtics, you saw his big hands, his supple, sloping shoulders and long arms. Those were the optics of Cousy. He wore a thirty-five-inch sleeve; his fingertips reached nearly to his knees. Small wonder he so easily transferred the ball behind his back. He looked like he weighed only about 150 pounds (actually, thanks to his thighs, he weighed 185), and at six-foot-one, if he jumped as high as he could he might reach only halfway up the net.

But physiology didn't make him Cooz. Biography defined him. He lived and played with blast-furnace intensity. He sought to break free of his tenement-house origins and the dysfunction in his parents' marriage by winning basketball games and by defeating enemies of all kinds, including a sense of being an outsider in his own world.

At the center of this inner tumult was his mother, Juliette Corlet Cousy, a native of France, once tall and attractive. When she cooked her husband's favorite meal, pot-au-feu-beef stew with vegetables, including sliced potatoes with butter, fried to a crisp-it was as if she had transported the French countryside to a dinner table in Queens. From France she also brought a prejudice so strong it scarred her personality: She despised Germans. She trembled with rage at the mention of anything, or anyone, Germanic. If misfortune came, Juliette Cousy knew its source. It was the Germans! She had witnessed the Germans' wrath during World War I. They trampled French farms, trampled the French way of life, and she never forgot that, even after migrating to America.

As a boy, Cousy saw her scars. During World War II, he walked with his mother to see a neighborhood storekeeper in St. Albans, Queens. In the Old World she would expect a smile or warm embrace, as in Dijon or Paris. But this storekeeper drew back and said stiffly, "What can I do for you?" It didn't take much to stir her anger. Offended by his tone, Juliette jerked her young son's hand, and they left the store at once. Outside, she muttered to him, "That sale Boche!"

When her mood turned black, as it often did, she spat out those words, "Sale Boche." Dirty German. She was at war with Germany, with her husband, with herself, and with the hard times in which they lived. Anyone she disliked or who had slighted her, whether of German descent or not, she dismissed as a sale Boche. Too often to forget, the young Cousy heard his mother's voice explode from the cellar of their house: "SALE BOCHE!" On those occasions, her wrath was more personal: She had taken aim, again, at her husband, the boy's father.

Juliette's husband, little Joe Cousy, bore the brunt of her rants. He had made the mistake of being born of French parents in a German-dominated region. He came from Alsace-Lorraine, on the northeastern edge of France up against Germany's northwestern border. The region had been claimed by Germany in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War. He had been conscripted by the German army during World War I, as so many other Alsatian farm boys had. Public records show Joe Cousy's place of birth as Welschensteinbach, its German name, but Joe always used the village's French name, Eteimbes. For Juliette, that was a distinction without a difference. If in her anger she needed Joe to be a dirty German, his parentage didn't matter.

A quiet, peaceful man, five-foot-six and stout, Joe was raised on the Cousy farm. There his family struggled to raise apples, cherries, and pigs. To his way of thinking, he was no more a farmer than he was a German, and breaking away to go to America was the boldest act of his life; Juliette, accustomed to life's finer things, loved him for all of that. With his new wife and her mother, Joe boarded the ocean liner Mauretania, pride of the Cunard Line, and set sail from Cherbourg on December 21, 1927.

For Juliette, their arrival in New York City was a homecoming of sorts. She had been born in New York and moved to Boston, where her French father, ClŽment Corlet, notable for his handsome, thick mustache, was ma”tre d' of the Hotel Touraine. When Juliette was five years old, Corlet and his wife, Mary, brought her to Dijon, in the Burgundy region of eastern France. She later worked as a secretary and taught language to children of affluent French families. As they boarded the Mauretania, Juliette was about six weeks pregnant with their son, the only child she would have.

Juliette's contempt for Germans intensified during the late thirties and early forties when she received letters from friends and family in France telling of the Nazis and their atrocities. Joe Cousy had begun work in America driving a taxi, his old Packard, in New York City. On July 5, 1928, he filled out papers for U.S. citizenship. But then came the Depression. Soon, with hardly anyone using taxis, Joe needed a job. Franklin Roosevelt came to his rescue: In his forties, Joe got a job with the Works Progress Administration digging ditches in New York City.

Her dreams deferred, Juliette became so high-strung that kids in the neighborhood knew her as the crazy French woman. Hard times aged her quickly, her cheekbones becoming taut and severe. Assimilation wasn't easy. Juliette and Joe did not read the New York newspapers; nor, as best their son knew, did they vote. Juliette never quite understood basketball, or even television. Years later, to watch The Ed Sullivan Show, she put on a nice dress at home. When her son asked why she dressed up, she said, "Oh, Mister Sullivan sees me. I see him and he's looking at me."

Her son saw more than the eccentricities. He knew her softer, loving side, the way she had gently coaxed him out of his boyhood nightmares and sleepwalking expeditions; she found him once sitting on the third-story ledge of their Manhattan tenement, where he had awakened screaming in French. She waved a white handkerchief from their window when it was time for dinner, and his buddies would say, ''Hey, Frenchy, the handkerchief is out!" When the young Cousy opened drawers at home, cockroaches scurried for cover, but his mother assured him that one day she would get him out of the noise and stench and poverty of their Manhattan neighborhood. Of course, as a boy, he assumed that everyone was poor. Despite their own ethnic differences and prejudices, Juliette and Joe Cousy quickly had won the privileges of whiteness. They lived in the big-city melting pot or, as their son would later call it, "the mŽlange." His closest friends during childhood had last names like Gannon, Field, Kennedy, Blake, and Hackford, all of them white. There were no people of color in his neighborhood that he knew of, no blacks or Hispanics or Asian Americans, and only a few Jews. During the Depression, with hard times and soup lines in Fiorello La Guardia's city, Cousy played stoopball and boxball and pilfered bananas from pushcarts. He never felt threatened in his roughneck neighborhood, though once he saw someone shot dead.

During the late thirties, as the Cousys searched in less crowded areas for a new place to live, Juliette said to her son, "Roby, look at all the green grass! Someday you'll live where there is plenty of it." And once, touring St. Albans in Queens, she said, as if in a dream state, "Roby, breathe deep."

Joe and Juliette spoke French at home and German if they didn't want their young son to know what they were saying. As a boy, Cooz spoke French, thought in French, dreamed in French, and talked French in his sleep. But he wanted to be an American. It didn't help that he had a speech impediment: his Rs sounded like Ls. His schoolmates began to call him Flenchy, and a speech teacher made him try to say, over and over, "Around the rugged rock, the ragged rascal ran." His Ls poured forth; "Alound the lugged lock . . ."

The tension of his parents' marriage traumatized him. Juliette loomed over the household. His grandmother, Marie Corlet, lived with them and became his safety net. She made sure he went to church and didn't stray from Catholicism. She made him promise that one day he would attend a Catholic college.

Joe Cousy put his taxi in hock in 1940 as a down payment for a $4,500 house in St. Albans. He and Juliette proved resourceful. They lived, and cooked, in the bare-walled cellar, and with their son climbed three flights up the back staircase each night to sleep in the attic, leaving the rest of the house for renters, whose payments helped cover their mortgage. They rented out a five-room apartment on the first floor, a two-room apartment on the second, and a single room on the third. Juliette kept the place clean, and Joe fixed anything that broke. They brought a radio into the cellar to lighten their spirits. Their house in St. Albans was better than their Manhattan tenement, but that wasn't saying much. On summer nights, the attic became an oven. At times when Cousy awoke screaming from a nightmare, his mother would turn on the light to see welts on his back, the work of bedbugs.

Joe never said much. With his boy, he shared no profound father-son conversations about his war experience, or in fact any experience. He had been married to another woman who died during the first war, but Juliette decreed the subject of Joe's late wife off limits. Many years later, when his son was a basketball celebrity, Joe told a sportswriter that he had raced automobiles before the first war and that, in the 1920s, with his family's farm reduced by war to mud, he fixed cars and rented one of his own to drive rich families on tours across Europe.

Joe wasn't home much. He drove his taxi at all hours, no doubt to escape his wife's wrath. They were in the cellar the first time Bob Cousy saw his mother strike his father. Joe was an easy target: one big room, no place to hide. Juliette smacked his head. Joe did not defend himself. He did not react at all.

"Sale Boche!" Juliette screamed.

She would never let him forget that he had once been in the German army even though he thought of himself as French. Cowering in a corner, the young Cousy watched his mother come undone. It happened this way more than once, Juliette calling Joe a dirty German and striking him. Her blows struck with force. Sometimes Joe threw up his hands in defense, other times not.

My poor father, Cousy thought. He wondered how his father could say nothing. He didn't want him to strike back. But sit there and take it? Even as a boy, Cousy understood there was more to it than a wife's anger at her husband.

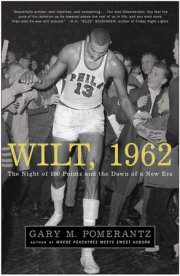

Copyright © 2018 by Gary M. Pomerantz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.