List of Illustrations

1. L’Attente (Margot), 1901 (oil on canvas), Pablo Picasso/Museo Picasso, Barcelona, Spain/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library

2. Portrait of a woman at the Rat Mort, c.1905–6 (oil on board), Maurice de Vlaminck/Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/The Bridgeman Art Library

3. Au Lapin Agile, c.1904–5 (oil on canvas), Pablo Picasso/Private Collection/Photo © Boltin Picture Library/The Bridgeman Art Library

4. The Artist’s Wife in an Armchair, c.1878–88 (oil on canvas), Paul Cézanne/Bührle Collection, Zurich, Switzerland/The Bridgeman Art Library

5. La Joie de vivre, 1905/6 (oil on canvas), Henri Matisse/The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA/© 2014 Succession H. Matisse/DACS, London. Digital image: The Bridgeman Art Library

6. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 (oil on canvas), Pablo Picasso/Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library

7. The Bathers, 1907 (oil on canvas), André Derain/Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library

8. Caryatid, 1911 (pastel on paper), Amedeo Modigliani/Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library

9. Paris, Montmartre (18th arrondissement). View of the Scrub, c.1900. Roger-Viollet/TopFoto

10. Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), 1904 (b/w photo), French photographer, 20th century/Musée de Montmartre, Paris, France/Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library

11. Henri Matisse (1869–1954). The Granger Collection/TopFoto

12. Gertrude Stein with Alice B. Toklas. The Granger Collection, New York/TopFoto

13. Gertrude Stein in her living room with her portrait by Picasso, 1946 (gelatin silver print), André Ostier/Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/The Bridgeman Art Library

14. Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920). The Granger Collection/TopFoto

15. Paul Poiret (1879–1944). The Granger Collection, New York/TopFoto

16. Paris, Montmartre (18th arrondissement). The cabaret Lapin Agile, c.1900. Roger-Viollet/TopFoto

17. The Moulin de la Galette, Paris. Alinari/TopFoto

18. Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) with her brothers Leo (left) and Michael. Photographed in the courtyard of 27, rue de Fleurus, Paris, c.1906. The Granger Collection/TopFoto

19. Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929). Roger-Viollet/TopFoto

20. The Bateau-Lavoir, Montmartre, Paris. Roger-Viollet/TopFoto

21. Georges Braque. © Ullsteinbild/TopFoto

22. Paris, Montmartre (18th arrondissement). The rue Saint-Vincent on the level of the cabaret Lapin Agile, c.1900. © Roger-Viollet/TopFoto

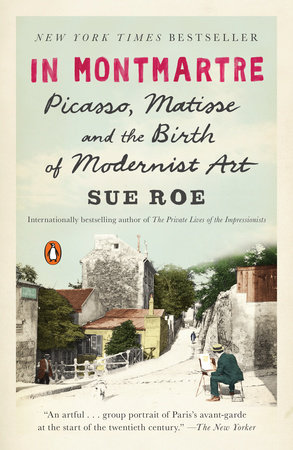

Introduction

Inside the glowing-red simulated windmill, the girls danced the cancan to Offenbach’s deafening music, tossing their heads, their petticoats raised in a froth of white as they kicked their legs, revealing tantalizing glimpses of black and scarlet. They performed on the dance floor, mingling with the punters – aristocrats, celebrities, artists, boulevardiers and strangers; in those days there was no raised platform in the Moulin Rouge. In the daytime, on a stage rigged up in the gardens outside, there were open-air performances of singing and dancing, including makeshift ballets danced by the young Montmartroises everyone still called the ‘little rats’. To the side of the stage stood a model elephant, an incongruous exhibit left over from the 1889 World Fair, which housed the orchestra. It was at night, however, that the place really came into its own.

When the young Pablo Picasso arrived in Paris in October 1900 he made his way up the hillside of Montmartre to the lodgings he was borrowing from another Catalan artist before heading down to investigate the nightlife. At first, he was dismayed by the Moulin Rouge, finding it tinselly and expensive in comparison with the all-male taverns of Barcelona. He had been expecting artistic bohemia, not cavorting women. His Catalan friends, habitués of Montmartre, usually gathered at the top of the hillside, around the place du Tertre, preferring the shady, cramped little bars where they could drink and talk until dawn. Up there, in the heights of Montmartre, Picasso discovered the other, less outrageous popular dance hall, the old Moulin de la Galette, a real converted windmill where the neighbourhood girls and their beaux still danced into the small hours, as they had in Renoir’s day. Here, artists such as Henri Matisse and the Dutch painter Kees van Dongen (whose portraits of women with elongated limbs, monocles and short haircuts would later earn him a central place among modernist artists) went to sketch the dancers. Nevertheless, it was not long before Picasso succumbed to the allure of the cabarets at the foot of the Butte, where prostitutes spilled out into the streets, strolling along the boulevards. They were among his first Parisian subjects.

A Spaniard, Joseph Oller, had created the Moulin Rouge on the site of the old Reine Blanche. Ingeniously, he constructed it in the shape of a windmill (competition for the old place at the top of the hillside), with eye-catching sails and red electric lighting, opening it under its new name in 1889. He commissioned a painting by Toulouse-Lautrec for the foyer and poached the dancers with the best legs from the Élysée Montmartre. From the day it opened the red ‘windmill’ became Montmartre’s most popular attraction, even in summertime; when Parisians left the city for their country retreats, visitors came in from all over the world, gravitating towards Montmartre in search of cheap cabaret entertainment and lively nightlife. Behind the scenes, the Moulin Rouge traded prostitutes, but the visitors (and their wives) who patronized it saw only the surface gaiety and glamour of the place, enjoying the atmosphere of risqué sensuality without taking any real risk.

As for the performers, they were unforgettable. La Goulue (‘Queen of the French Cancan’) belted out songs celebrating the low life of Montmartre. Her replacement, Jane Avril, had been treated for hysteria by neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot in his clinic at the Salpêtrière mental hospital before dancing in nightclubs on the Left Bank. She later grew bored of these and came to Montmartre, where she shook off her inhibitions in the Moulin Rouge, spindly legs flying in all directions. She was not interested in material things, she once said, only in l’amour.

The poor, the displaced, those who had known destitution, deprivation and suffering, seemed to find a natural home for their talents in Montmartre; the district was already suffused with its own distinctive melancholy. Higher up the hillside – up the narrow steps, past the small, tree-lined squares – windmills still stood among the gardens and vineyards that covered the steep slopes. Though they no longer milled flour, it was to these that the Butte owed its distinctive, fragile beauty, immortalized in the sketches of van Gogh, who briefly lived there during the 1880s and painted the view from his attic window in shades of greyish blue.

In later years, Picasso looked back with nostalgia on Montmartre, where he lived out the formative years of his career and established the emotional foundations of his work. ‘My inner self,’ he once said, ‘is bound to be in my canvas, since I’m the one doing it . . . Whatever I do, it’ll be there. In fact, there’ll be too much of it. It’s all the rest that’s the problem!’ The ten years following his arrival in Paris, he painted the world of Montmartre, seen through the prism of his inner life, responding, too, to the emotions and ideas of those who converged on the place during the first decade of the twentieth century – Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, van Dongen, Modigliani, couturier Paul Poiret and writer Gertrude Stein – each of whom became his friend. They were all inspired by the world of Montmartre, responding to the mood of artistic self-consciousness which had replaced the decadence of the Belle Époque and came to characterize the modern age. ‘All the rest’ – the plethora of challenges set by the changing social climate, their awareness of the art of the past, the technical demands presented by their rapidly emerging ideas – would increasingly make claims on them.

• • •

During the first decade of the twentieth century, art, as well as entertainment, was profoundly influenced by travellers and outsiders. Artists from Spain, Italy, Russia and America converged on Montmartre, providing entertainment, inspiration and fresh social interaction. Newcomers to the artistic scene were brought together by an unlikely nexus of brilliant talents – including Gertrude Stein, Paul Poiret and art dealer Ambroise Vollard – and the decade saw the formation of a new avant-garde. In the village environment at the top of the hillside, in muddy lanes and broken-down shacks, inspired by the circus and silent movies, close to the locals still dancing the night away in the old Moulin de la Galette, the leading artists of the twentieth century spent their early years living among acrobats, dancers, prostitutes and clowns. Their spontaneity, libertine lifestyles and love of popular culture contributed to the bohemian ambience of haute Montmartre and to the development of path-breaking ideas. By the end of the decade Matisse was exhibiting his dynamic works La Danse and La Musique, Picasso had shocked his friends with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Poiret was dressing le tout Paris in garments inspired by the costumes worn by the performers in the Ballets Russes production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade and every gallery in Paris was showing cubist art. How did all this come about?

The decade saw the emergence of major artistic discoveries as well as significant social change. In the years following the end of the Belle Époque, young artists weary of decadence and satire were already looking for new subjects and novel, more rigorous methods of painting which reflected their feelings about their lives. As an incomer, Picasso was fascinated by what he saw around him – itinerant circus performers and acrobats, streetwalkers and the day-to-day life of those who lived in the shanty town that was the northern flank of Montmartre. At the foot of the Butte dramatic shifts were beginning to take place in the world of entertainment. During the years immediately following 1900, cinema took over from the circus as a major recreational diversion, and its progression from circus venues to designated spaces and the transition from the earliest silent movies to motion pictures with narrative, featuring popular screen stars, were also profoundly influential; the artists who gathered in Montmartre modelled themselves, for fun, on film stars and comic-book heroes.

In retrospect, it seems that, if the Impressionists had sought to capture on canvas a moment in time, the natural world en passant, by contrast, in Montmartre between 1900 and 1910, there was a spirit of iconoclasm at work. With the rise of photography as an artistic medium, the painters’ previous ambition of imitating life in art now belonged to photographers and, increasingly, cinematographers. The aim of painting was now to find ways of expressing the painter’s own response to life, vividly demonstrated by the early work of Derain, Vlaminck and van Dongen, whose vigorous forms and bold colours would earn them the nickname ‘les Fauves’ (‘wild beasts’). With this decade, which witnessed searches for originality and artistic impersonality, came – paradoxically – vibrant personalities. New relationships suddenly seemed possible, between artists and their patrons, their dealers, their lovers – and among the artists themselves. Those who gathered in Montmartre just after the turn of the century soon became competitive and sometimes combative, falling regularly in and out with one other, discovering, exchanging and strategically guarding original ideas. They sought personal freedom and innovative creative directions, yet they were not without nostalgia. In the ‘cabaret artistique’ at the top of the Butte, everyone sang the songs of the 1830s, accompanied by Frédé, the proprietor (who sold fish, and the odd painting, from a cart in the daytime), on his guitar. The red-shaded lamps and rough red wine reminded the Catalan artists of home. More significantly, in forming new methods and ideas, the artists also drew on the art of the past – El Greco, the Italian primitives and the classical art of ancient Greece. When African and Indonesian masks and carvings began to appear in Paris, the excitement they caused was heady, and lasting.

As the decade unfolded, artists continued to spur one another on, forming allegiances, making discoveries, sparring and changing sides. Derain and Vlaminck, still painting together in Chatou, a suburb of Paris, in 1900, began to follow Matisse; by 1910, the ideas they were calling into question were Picasso’s. Braque was a friend of Marie Laurencin (the only female painter in their circle) before he began working closely with Picasso – who loathed her. Paul Poiret, the first couturier to treat fashion as an art form and to compare himself with the painters of his circle, knew Derain and Vlaminck from the early days, when all three lived by the Seine in Chatou; within a few years, the designer was throwing huge parties, inviting Picasso and his friends to gatherings on the colossal houseboat he kept moored on the river. Gertrude Stein sat for Picasso ninety times (or so she claimed) in the beaten-up Bateau-Lavoir, making her way every week from the Left Bank to Montmartre. Intrigued and inspired by Picasso, she began giving her famous soirées; then the artists came to her. Against the backdrop of continual discussion in the cafés and bars of Montmartre, the subtle almost-feud between Matisse and Picasso played itself out in continual stand-offs and rapprochements as the world of artistic Paris evolved – as Alice B. Toklas once put it – ‘like a kaleidoscope slowly turning’. By the end of the decade, the Futurists were launching their plangent appeal for aggressive action, announcing ‘a new beauty: the beauty of speed’, calling for the radical renovation of techniques of painting and denouncing all forms of imitation. In Montmartre, much of what they dreamed of was already happening.

The years that saw the birth of modern art in Paris were those directly following the turn of the century, before the Great War. By 1910, Paris had become a hive of creative activity in which all the arts seemed to be happening in concert. The cross-fertilization of painting, writing, music and dance produced a panorama of activity characterized by the early works of Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck and Modigliani, the appearance of the Ballets Russes and the salons of Gertrude Stein. The real revolution in the arts first took place not, as is commonly supposed, in the 1920s, to the accompaniment of the Charleston, black jazz and mint juleps, but more quietly and intimately, in the shadow of the windmills – artificial and real – and in the cafés and cabarets of Montmartre during the first decade of the twentieth century. The unknown artists who gathered there and lived closely overlapping lives are now household names. This book tells their story.

PART I

The World Fair and Arrivals

1.

The Arrival of Picasso

On 14 April 1900, Paris was transformed into a vast garden shimmering with light, glass and steel. Visitors flocked in from all over the world for the World Fair, opened by President Loubet of France to the sound of the Marseillaise. The public approached through the Porte Binet, an exotic red and gold archway on the place de la Concorde, lit up at night with thousands of multicoloured electric lights. Before the close of the fair in October, a group of Catalan artists arrived, four of them posing beneath the archway, arms clasped, while the fifth, Pablo Picasso, made a quick sketch of his friends. He added himself in at the front of the group, marking himself, in the drawing, ‘Me’. He had just arrived in Paris for the first time, to see his painting Last Moments displayed at the fair.

The streets bustled with visitors to the exhibition halls, which stretched across the city in the shape of a letter ‘A’, from the École Militaire to the Trocadéro. The traffic was infernal, the rumble of horses pulling carriages across the cobbles almost deafening. For the 39 million visitors to the fair, the most popular exhibit was the Palace of Electricity, which transformed the old Trocadéro (now the Musée de l’Homme) into a dazzling, animated display. At night, even the River Seine sparkled, the boats strung up with electric lights. The grands cafés hummed with visitors. The chanteuses still sang, some nights, in décolleté sea-green dresses and long black gloves perhaps, at the Café des Ambassadeurs. Night and day, stylish women strolled along the boulevards, dressed by Doucet or Worth in heavy satins and silks with nipped-in waists, bustles and hats top-heavy with ornamental feathers or flowers. The streets were no less decorative. In the grand avenues, art nouveau – le style 1900 – predominated, embellishing the apartment buildings, façades and interiors of cafés, shops and bars and the entrances to the newly constructed Métro stations. The interiors of the grands cafés boasted ornate gildings and friezes in the new style, intertwined sheaves of corn and laurel leaves set off by glittering mirrors and chandeliers.

In the immense hall of the Salle des Fêtes, Gaumont news was being projected on to a gigantic screen, with spectacular close-ups and the earliest examples of synchronized sound. ‘Every member of the audience,’ marvelled one visitor, ‘had a listening-tube, hung on the back of the seat in front, with a pair of little knobs that you placed in your ears; at the other end of the listening-tube a phonograph played a text synchronized with the pictures.’ Gaumont, Pathé Lumière and Raoul Grimoin-Sarran all showed films at the fair, taking the opportunity to show off their most spectacular technical advances. Lumière, in particular, showcased the company’s stunning developments in colour photography, ‘visions d’art’, photographic stills tinted with ‘natural’ colour – ‘roses twelve feet in diameter, delicately shaded, finely modelled, so subtle and elegant!’ Outside, American dancer Loie Fuller, pioneer of improvisation, performed her serpentine moves in her booth (rejected by the Paris Opèra, she was appearing as a curiosity at the fair), her coloured drapery eerily lit, and making her look (as someone remarked in passing) like a human bat . . .

The Guide Hachette made great claims – ‘the Fair shows the ascent of progress step by step – from the stagecoach to the express train, the messenger to the wireless and the telephone, lithography to the x-ray, from the first studies of carbon in the bowels of the earth to the advent of the airplane . . . It is the exhibition of the great century, which opens a new era in the history of humanity.’ Entire streets had been transformed into simulated colonial dwellings; pavilions from across the world exhibited national products, electric lights, hot-air balloons, experimental flying machines, and arts and crafts. High in an insignificant corner of the Spanish pavilion hung Picasso’s Last Moments.

• • •

Picasso arrived in Paris two weeks before the close of the Fair, on 25 (his nineteenth birthday) or 26 October. He had travelled from Barcelona with his friend Carles Casagemas, a moody fellow painter with a taste for Nietzsche and a tendency to depression and anarchy; he was linked with the Spanish liberation movement. They arrived by way of the Gare d’Orsay, and made their way along the bank of the river, heading for Montmartre. In Barcelona, they had been fitted out for the occasion by a local tailor in arty black corduroy suits with loose jackets and high collars designed to hide the absence of a waistcoat (even, if times got really hard, a shirt). The wherewithal for Picasso’s trip had been provided by his parents, who by the time they saw him off at the station had little more than the loose change in their pockets to see them through to the end of the month. The local newspaper, notified most likely by Picasso himself, had duly announced the departure for the French capital of two of Barcelona’s most promising young artists.

On the Left Bank they briefly stopped off to visit a friend in Montparnasse before crossing the river and making their way to the Butte de Montmartre, either on foot or perhaps by omnibus. If the latter, they would have taken the Batignolles–Clichy–Odéon imperiale, pulled by three dappled grey horses, the cheapest ‘seats’ buying its passengers a place on the crowded roof, legs dangling, along the boulevard Rochechouart, past the old model market in the place Pigalle (where ‘types’, all got up in various costumes – shepherdesses, Marie Antoinettes, harlequins – could be hired for genre paintings), then on up the steps of the hillside; some of the pair’s friends from Barcelona were living there in small studios. They hauled their luggage up as far as the grandly named Hôtel Nouvel Hippodrome (probably in fact a maison de passe) in the rue Caulaincourt, which was lined mainly with shacks and brothels. There they left their possessions, before continuing the climb up the hillside as far as the rue Gabrielle, where at number 49 their friend Isidre Nonell, a painter of sad-faced women, kept a studio. In Montmartre they found themselves in a hilltop village with squat crumbling houses, vineyards and squares bordered with chestnut trees, the outlooks plunging down into the mists of Paris, where life was lived slowly and quietly, like going back in time. On low green benches old bohemians sat watching the world go by, while the local urchins ran about, scruffy dogs wandered here and there and sparrows pecked in the dirt. The artists who gathered in the cafés were mainly Catalans, poets and aspiring amateurs.

When Picasso went down to the fair to see his painting, the artists who accompanied him were his travelling companion, Carles Casagemas; Ramon Casas, a society portraitist who painted the political and financial elite of Barcelona; Miquel Utrillo, artist, writer and shadow puppeteer; and Ramon Pichot, whose works showed the influence of Gauguin’s Pont-Aven paintings. (Pichot owned a dilapidated, rose-coloured cottage in Montmartre, near the rue Cortot, where, at number 10, in the 1880s, both Gauguin and van Gogh had once briefly lived.) Casas, Utrillo and Pichot were all ten or more years Picasso’s senior, all old habitués of Montmartre. Another of their crowd was a ceramicist, Paco Durrio, who had been in the area since van Gogh and Gauguin’s day. He still had paintings by the latter in his studio (from the Pont-Aven years), which he pulled out at any time of the day or night for anyone who wanted to see them – until, one day, they mysteriously disappeared.

In the Spanish pavilion, Picasso discovered that his traditional depiction of a Spanish deathbed scene was not prominently displayed (the picture no longer exists, as he later painted over it). The Catalan friends progressed to the Grand Palais, the glorious, purpose-built exhibition hall (not really a palace) which, in architectural terms, was the most notable feature of the 1900 World Fair. An example of late-Beaux-Arts splendour, it was part of the newly built complex comprising the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais and the Pont Alexandre III, which had been designed to celebrate the Franco–Russian alliance signed in 1894 and opened to coincide with the commencement of the fair. Inside were displays of major works of art, the French section dominated by the work of academic painters from the École des Beaux-Arts: portraits, landscapes and seascapes, religious scenes, draped nudes and historical tableaux. The ‘modern’ section (consisting of eighteenth- and early- to mid-nineteenth-century work by David, Delacroix, Ingres, Daumier, Corot and Courbet) hardly represented the avant-garde. Impressionism – brought before the public in the form of the collection bequeathed by Gustave Caillebotte as recently as 1896, was represented only by Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Monet’s Water Lilies. Works by James Ensor and Gustav Klimt were shown by foreign exhibitors, but there was no trace here of anything by Gauguin or van Gogh, both of whom were still considered subversive or dismissed as mere poster artists. In Paris, their works were barely talked about and almost never seen, except occasionally in the small galleries in Montmartre.

When Picasso saw the exhibition of modern (as opposed to ancient) French masterpieces in the Grand Palais he found his first glimpses of David, Ingres and Delacroix awe-inspiring; he was hardly sufficiently au fait with French modern art to notice the absence of contemporary work. Soon after his arrival in Paris, he made his first visit to the Louvre, where he marvelled at the works of ancient Egypt and ancient Rome. In the Musée du Luxembourg, he saw Caillebotte’s collection of Impressionist art, acquired in June 1894, which it had taken the museum two years to put on display. The professors of the École des Beaux-Arts had threatened to resign if the legacy was accepted, so the State had accepted only part of the collection – eight works by Monet, three by Sisley, eleven by Pissarro, one by Manet and two by Cézanne. Picasso was dazzled by his first glimpse, particularly, of works by Monet and Pissarro; though he had begun to study new ways of painting light in Barcelona, he had seen nothing like this. What mostly impressed him as he explored the streets of Paris, however, was the poster art. Posters by Steinlen – the Swiss-born painter who painted scenes of low-life Montmartre (couples kissing on street corners, or huddled together in bars), and publicity material for the cabaret where the literati gathered, the Chat Noir (including the still-famous poster featuring the alarming black cat with yellow eyes) – and Toulouse-Lautrec, who brought the life of the café-concerts to the streets, were pasted on every wall, even in the poorest districts. Picasso could see immediately that these quasi-anarchist depictions of urban reality were not merely decorative or provocative but progressive works of art.

• • •

By the time he made his first visit to the French capital, Picasso was already an accomplished draughtsman. As a young child in Malaga he had been taught to draw by his father, José Picasso, an art teacher and curator of the municipal museum. Since his schooldays, young Picasso had shown little aptitude for anything but drawing. He seems to have been happy in Malaga; asked once to name something characteristic of his native city, he recalled a singing trolley-car conductor who slowed and increased the speed of the car to fit the rhythms of his song, sounding his bell in cadence as he bowled along. But he was insecure at school, uninterested in his lessons and obsessed by the worry that his parents would forget to collect him at the end of the day. He always took something of his father’s to school – his cane, or a paintbrush – to be sure of being redeemed along with the treasured object. When he was thirteen, his eight-year-old sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria. The family moved to Barcelona, where his father accepted a job at the art college, but he was never happy there: life in Barcelona was overshadowed for both parents by the loss of their daughter. Pablo, however, seemed resilient. He attended classes at the art college, where, aged just fourteen, he produced two portraits of old Galician villagers which demonstrated not only his extraordinary drawing skills but also, it was remarked, an unusual degree of psychological observation for one so young.

In autumn 1897, he left Barcelona to attend the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, where his education was traditional and rigorous. Students practised first with two-dimensional images, then with plaster casts, before working from life, learning technique partly by consulting the drawing manuals left open in the studios at pages showing perspective schemes, geometric shapes or drawings of eyes, arms and noses, Greek and Roman statues and examples of bones, musculature and veins. Thus, by the time he graduated, Picasso already possessed a strong and varied artistic vocabulary, the result of a thorough classical training.

In spring 1898, he experienced the ways of life in rural Spain after falling ill with scarlet fever. Sent to the countryside to convalesce, he spent June of that year with the family of a friend in Horta, a tiny, deserted village where life was still essentially feudal. There, he learned to speak Catalan, living in the countryside and working in the open air. The experience had a profound effect on him; rural life and the sense of freedom from material considerations suited him; he later said he had learned everything he knew in Horta, where day-to-day experiences included attendance at a village autopsy. Picasso saw one performed on an elderly woman who had been struck by lightning; he fled before watching that of the woman’s granddaughter, who had suffered the same fate. Perhaps the experience of seeing the body segmented informed his later, cubist vision. Norman Mailer thinks so, though Picasso’s cubist style emerged much later, some ten years after the village experience. (Picasso was not the only painter to have observed a village autopsy: Cézanne had seen them, too, in his native Provence.)

When he returned to Barcelona in February 1899, no longer a student, Picasso was ready to embark on his career as a professional artist. He shared a studio with the moody Casagemas, both of them trying to make their way as graphic artists, illustrating posters and restaurant menus and painting scenes of local life, vignettes of cabaret performers, boulevardiers, priests, street orators and musicians, dancers and poets. Picasso was good at these; some of the older artists called him ‘little Goya’.

In Barcelona, the lives of the city’s artists revolved around Els Quatre Gats, a large tavern decorated with ornamental tiles in the traditional Spanish style in a narrow cobbled alley running between high buildings in the then unfashionable old part of town. ‘The Four Cats’ was a Catalan expression meaning (approximately) ‘the only four cats in town’; the tavern’s educated, well-connected clientele saw itself as exclusive. Here, everyone gathered to display new work and to debate the issues of the various strands of Catalan ‘modernisme’, which was broadly Symbolist – depictions of loss, yearning and erotic desire inscribed within religious and mythological iconography; the Els Quatre Gats crowd prided itself on its knowledge of the Decadents and on its own intellectualism. The basis of their ideas was as much literary as pictorial; they craved bohemianism, art for art’s sake, decadence, the libertine life of the ‘moderns’, a break from the traditions and prejudices of the bourgeoisie (their parents). Their own national modern artist, Gaudí, they dismissed as too conservative (his architectural eccentricities had been found acceptable by the establishment). They read the Symbolist poets, Verlaine, Mallarmé and Baudelaire, all of whose work Picasso was familiar with. Their idea of Paris was bars and café-concerts, nightlife and wild women.

Paris was the artistic mecca of the world, and many of the Els Quatre Gats crowd made regular visits to the French capital. Back home in Barcelona, they mounted exhibitions of their work (landscapes of local scenes and portraits of one another wearing bohemian scarves and large overcoats, paintbrushes sticking out of their pockets) and dreamed of Paris, since the tavern in Barcelona offered neither the decadence nor the overt sexual appeal of the French boîtes or café-bars; and no woman would ever have been seen in Els Quatre Gats. In Barcelona, there were brothels behind closed doors, but prostitutes would never be seen openly drinking in the taverns or strolling through the streets, as they were in Montmartre.

As for ‘modernisme’, Picasso’s biographer John Richardson explains the vagueness of the term, the word perhaps best described as ‘Catalan art nouveau with overtones of symbolism’, and believes that the eclectic intellectual, artistic and literary movement was essentially born out of the Renaixença, or Catalan Cultural Revolution – the recognition that the region was closer in its cultural aspirations to the rest of Europe than to the conservative values and beliefs of Spain. A group of artists from Els Quatre Gats, including Picasso’s friends Ramon Casas and Miquel Utrillo, had been instrumental in promoting the values of the Catalan Cultural Revolution, especially since spending time in Montmartre, where in 1891 they had lived for a while in an apartment above the Moulin de la Galette. Utrillo had an even longer association with Montmartre. In the early 1880s, he had lived there with Suzanne Valadon, the daughter of an unmarried laundress who had been the mistress of Toulouse-Lautrec (and, briefly, Erik Satie) before meeting Utrillo. She had trained as a tightrope walker before her career as a circus performer came to an abrupt end when she fell and injured her leg. She had also modelled for Degas, who discovered her talent as an artist, effectively launching her career as a painter. In 1883, she had produced a son, Maurice, rumoured to be the child of Utrillo, but, though he signed the paternity papers, she continually taunted her son by refusing to tell him who his father was.

In Spain, the group of ‘modernistes’ had founded an arts centre in Sitges, a village twenty-five miles from Barcelona, where they had held a series of exhibitions and concerts which became a festa modernista of art, music and drama. In an introduction to one of the first concerts, they announced their aims and intentions: ‘to translate eternal verities into wild paradox; to extract life from the abnormal, the extraordinary, the outrageous; to express the horror of the rational mind as it contemplates the pit . . .’; they had all read Nietzsche and Rimbaud. ‘We prefer to be symbolists and unstable,’ the speech went on, ‘and even crazy and decadent, rather than fallen and meek . . .’ As John Richardson also points out, unfortunately, they were none of them sufficiently skilled or imaginative to be able to transpose such ideas into paint . . . except for Picasso. It would not take the local artists and writers in Montmartre long to notice that here was someone who painted in a way no one had seen before.

On their first evening in Paris, Picasso and Casagemas wrote home. They were disappointed by the nightlife, Picasso’s friend reassured his parents: the famed boîtes at the foot of the hillside seemed to them nothing but fanfare and tinsel, papier mâché stuffed with sawdust; it was all too showy and expensive for them – entry to the cheapest palais de danse, even the cheapest theatres, was steep, at one franc. So far, their dream of Paris seemed to have little to do with the reality. Amorous couples like the ones Steinlen depicted in his paintings stood entwined after dark in the rue Saint-Vincent, a narrow alley beyond the rue Cortot where the single sputtering gas jet could be relied upon to fizzle out no sooner than it was lit. Aristide Bruant, in his day, had sung songs about this street, but this was not the Montmartre of la Goulue and the Moulin Rouge. Montmartre at the top of the hillside consisted of crumbling houses, tiny, cramped studios in dilapidated buildings, shabby cafés and gloomy bars smelling of soup and cheap red wine.

Down at the foot of the hillside, Picasso and Casagemas explored the boulevard de Clichy, finding it ‘full of crazy places like Le Néant, Le Ciel, L’Enfer, La Fin du Monde, Les 4 z’Arts, Le Cabaret des Arts, Le Cabaret de Bruant – and a lot more which had no charm but made lots of money: a Quatre Gats here would be a goldmine . . .’ As for the Folies Bergère and the Moulin Rouge, if they entered those dens of vice, where the crowd exploded with excitement while the female performers high-kicked and did the splits, such places went unmentioned in the letters home. The two friends had certainly, in any case, discovered some of the least salubrious places in Montmartre. Most ‘cabarets’ were merely small rooms, sparsely furnished with rough tables and benches behind unprepossessing shopfronts, the exception being L’Enfer, where the façade was as startlingly gothic as the entrance to a fairground ghost train. Compared to Els Quatres Gats, the lesser known boîtes in Montmartre were poky, tawdry and unexciting.

Casagemas continued his description of life in Paris with a long (surely spoof) inventory of Nonell’s studio. Apparently, it boasted a table, a sink, two green chairs, one green armchair, two non-green chairs, a bed ‘with extensions’. A corner cupboard (not corner-shaped), two wooden trestle tables supporting a trunk, an oil lamp, a Persian rug, twelve blankets, an eiderdown, two pillows and lots of pillow cases . . . the list went on. (Perhaps it was just a playful recitative, written to entertain or reassure their families.) He omitted to add that three girls also seemed to be included. After a few days, Nonell returned from Barcelona, which now made three couples living in his studio. Picasso’s girl, who soon disappeared from his life, spoke no Spanish (nor he any French) and seems to have been called Odette. There were cooking utensils, wine glasses, bottles, flowerpots, a kilo of coffee . . . If the place really did contain everything Casagemas itemized, they were living in the lap of luxury by comparison with most of the surrounding dwellings in the heights of Montmartre.

2.

In Montmartre

‘À la moule!’ Frédé, with his long, matted beard, in battered felt hat and wooden clogs, came clumping through the lanes with Lolo the donkey, pulling a cart selling shellfish and the odd painting. ‘Voilà le plaisir, mesdames! . . . Du mouron pour les petits oiseaux! [seeds for your little birds] . . . Tonneaux, tonneaux! [sticks for your batons, for fire-lighting, or tightrope-walking] . . . Couteaux! Couteaux! [any knives, for sharpening?]’ Only the sounds of the merchants pushing their carts up the steep, muddy lanes, some of them mothers accompanied by dishevelled children, resonated against the peace and quiet of the hillside, undisturbed by traffic. Horse-drawn carriages did not get up as far as the top; even the funiculaire would not arrive until 1901. The area at the summit of the Butte was still a rural village, despite its attachment to Paris. It had hung on to its vineyards and scrubland; the water carrier still trudged through the streets, buckets suspended from a wooden pole across his shoulders; in the allée des Brouillards, women in plain, ankle-length skirts and simple blouses gathered water at the communal pump. Urchins played in the unpaved streets. Some of the small, shady restaurants in the lanes around the place du Tertre were little more than soup kitchens, where artists could invariably get a bowl of soup or a carafe of wine on credit. In the shops selling bric-a-brac, with jumbles of old chairs, clocks and cooking utensils piled up outside, you might still find the odd painting by Renoir or Manet. It had been known.

The indigenous population of Montmartre consisted largely of small tradesmen, entertainers, petty criminals, prostitutes, and artists with varying degrees of talent. The rural backstreets at the peak of the hillside provided shelter for ‘foreigners’, including those of Spanish, Flemish – even northern French – descent. They came to Montmartre in search of labouring jobs, cheap rents and tax-free wine, finding lodgings in half-derelict buildings and shacks, where they settled among the acrobats and whores, poor workers, mattress menders and circus performers of Paris, together with the factory workers, seamstresses, laundresses and artisans who made their way down the hill to their places of work every day, leaving the painters in the lanes sitting at their easels.

There had always been painters in Montmartre; its reputation as the centre of artistic life dated back to the reign of Louis VI, who was a great supporter of the arts. (Montmartre appears in records dating back to the twelfth century.) The Abbey of Montmartre, founded under his rule and built on the site now occupied by St Peter’s Church, between the place du Tertre and the Sacré Coeur, attracted generous donations, earning Paris the title of ‘Ville de Lettres’. Montmartre’s reputation had originally been founded not on prostitutes but on nuns, some of whom had achieved sainthood. During the next hundred years, other abbeys, monasteries and convents arose on the hillside, the thirty-nine windmills, also owned by the Church, providing food for the religious communities they housed. The Moulin de la Galette, originally named the Blute-Fin, was the hillside’s main vantage point. By 1900, there were no nuns and the windmills no longer produced flour, but there were still artists in the streets, painting to the sounds of the merchants who tramped up and down the lanes calling their wares.

The vibrant, glittering spectacle enjoyed by visitors to the 1900 World Fair hid the reality: this was still a period of great uncertainty for France. Between 1875 and about 1910, the franc stayed stable, with no inflation or deflation: a sou in 1875 bought the same amount of bread as in 1910; there was no income tax; but the wages of the workers remained debilitatingly low. If the pleasures and excesses of the Belle Époque were still evident, so, too, were the inequality and poverty that characterized the period. In the backstreets beyond the area designated for the fair, where the crumbling buildings were still medieval, dark and unsanitary and the roads unpaved, the poor mended mattresses in courtyards or sold their wares in the open air. The motley collection of battered goods and old iron spread out on the ground on market day was a reminder that not everyone enjoyed the fruits of prosperity. Female travellers sat at the roadside, their skirts spread, babies in their laps, selling heather. Around the outskirts of the city, bohemians set up camp in gypsy caravans like the ones van Gogh had painted, though rarely so colourful. In cramped workshops the seamstresses and laundresses who lived in Montmartre worked ten hours a day, seven days a week. To the painters they occasionally sat for, their life of labour made them ethereal, giving them a kind of ghostly beauty.

The greatest poverty in Montmartre was on the northern flank of the hillside stretching from the allée des Brouillards (where Renoir had lived before moving to the South of France) to the rue Caulaincourt, below the Sacré Coeur. The area of waste ground called the Maquis had effectively become an illegal shanty town, where the abject poor wandered in the scrubland in torn clothing and broken-down shoes among the chickens they reared for food. The area had been demolished with a view to the reconstruction of the future avenue Junot, the small farmers removed and their plots destroyed. However, subsequent building works had been halted because of problems with the terrain, and the poor had moved in, creating an ad hoc village with makeshift architecture. Those with no work and no prospects lived on chickens and rabbits, roaming around the Butte, their children playing in the mud. Here, too, was where the anarchists lived, in shacks with corrugated roofs, or beaten-up caravans.

Although, since the events of 1871 (when, following the war with Prussia, which left many Parisians starving, the government had responded to the protests of the Communards with mass executions), the anarchist movement had been strong, by 1900 the comrades were relatively peaceful; any trouble on the hillside was now more likely to be the result of personal dispute than anarchist revolution, though their newspapers, L’Anarchie and Le Libertaire, were still published from dingy rooms that passed for offices in the rue d’Orsel. In any case, during the next few years, the anarchist cause quietened down as the workers’ movements slowly began to recover. In 1901, workers gained the right to form associations and, in theory at least, there had been some improvements in working conditions; by 1900, women’s working hours had been reduced by law to ten hours a day. In practice, there was still great hardship. Conditions in the workplace remained brutally exploitative, the workers subject to long hours, appalling conditions and mercilessly cruel employers.

In a draughty barracks on the rue Sacrestan, Marcel Jambon, a well-known theatrical designer, paid the workers in his atelier one franc an hour to work a nine-hour day, bent double, crouched over canvases spread out on the ground ‘as if they were breaking stones’. They were kicked if they appeared to be slacking or disobeying orders. For three weeks in spring 1900, Henri Matisse was one of their number, put to work painting friezes of laurel leaves to decorate the halls of the Grand Palais for the World Fair. When the fair opened, he and a friend had come looking for work. They obtained the addresses of several ateliers de décoration and went from street to street, seeking employment. They ended up at Jambon’s, ‘a kind of hell-hole near the Buttes Chaumont’. Matisse got on well with his fellow workers, who taught him the tricks of surviving the gruelling conditions of the artisan’s life, but he was not a natural subordinate. After three weeks, unable to tolerate Jambon’s attitude any longer, he stood up to his employer. He was promptly sacked for disobedience, and found himself out of work once more.

In 1900, Matisse, aged thirty, was well in advance of Picasso in terms of his integration into the Parisian art scene, and already a familiar figure in Montmartre. When he arrived in the capital in the 1890s from his birth place in Le Nord, he was abandoning the study of law to focus on art, first at the Académie Julian – which disappointed him; he thought the place had seen better days – and subsequently in the courtyard of the École des Beaux-Arts, where students went to make studies of the statues ranged on pedestals in the open air, learning to draw from the antique while receiving instruction from various masters, who gave lessons in the courtyard. There he was taught by the ageing Gustave Moreau, one of the leading painters of the Symbolist movement (famous for his decadent painting of Salome, celebrated in Huysmans’ novel À Rebours), whose works depicted ‘a world of exotic fantasies, luxurious sensationalism, [and were] mystically erotic, hinting at sensual depravities existing under a veneer of religious iconography’.

Matisse foudromir.nd Moreau’s work disquieting (he preferred Monet’s), but he was fascinated by its elaborate textures – Moreau encrusted his pictures with jewels, stones and other ornamentation – and, although master and student diverged in doctrine, Moreau aiming for ‘a kind of literary and symbolic idealism’, Matisse for ‘pure painting’, prioritizing pictorial texture over narrative content, he found Moreau in person a sympathetic and encouraging master. Moreau took a great interest in his students and accompanied them to the Louvre, where he talked informally but passionately about the paintings. There, Matisse found himself surrounded by a wealth of styles and ideas that broadened his mind and made him reluctant to align himself with any particular genre or method. Anyway, Moreau had no desire to turn his students into theorists: ‘Don’t be satisfied with going to the Museum, go down into the street,’ he used to say; and it was by sketching at street corners, drawing horses, cabmen and passers-by that Matisse and his contemporaries learned the art of simplifying their drawing, capturing the atmosphere of crowds and single figures in animated motion by reducing forms to a few essential lines.

In 1898 (the year of Moreau’s death), Matisse enrolled at the Académie Camillo in the rue de Rennes, where the students received sporadic instruction from Eugène Carrière, painter of romantic portraits and idealistic depictions of motherhood. At the academy, Matisse noticed a student whose work seemed different from that of the others; this one painted portraits in simple, pared-down forms and scenes empty of symbolism. The student was André Derain, aged eighteen in 1898, who had spent his childhood in Chatou, where he still lived in lodgings at the riverside. In the 1860s, the Impressionists had painted there, in the open air. Derain was full of vitality. An avid reader, he seemed interested in everything – philosophy, occultism, spirituality and all manner of esoteric ideas. As a child, he had been taught by the Catholic Fathers and he remained essentially deist all his life. He also displayed a laconic sense of humour; someone once memorably compared him to an actor from the old days, ‘un grand comic triste de café-concert’. Once enrolled as a student at the Académie Camillo, he spent most of his time in the Louvre, where his particular passion was the art of the Italian primitives, ‘to me at that time’, as he later recalled, ‘pure, absolute painting’.

In the Louvre in those days, all sorts of people set up their easels to make copies of the old masters; there was no controlled entry and the place was full of students, who fraternized with the down-and-outs who sought shelter in the Salon Carré. Nobody thought to move them on. One day, Derain noticed a crowd gathered around a young artist working in the Primitive Room, copying Ucello’s The Battle – ‘transposing rather, for the horses were emerald green, the banners black, the men pure vermilion’. Recognizing him as an old schoolfriend, he took a closer look. Inspired by such a display of audacity, Derain himself began to experiment with colour. His first work as an inventive colourist was a copy of Ghirlandaio’s Bearing the Cross which he kept all his life; when, in later years, he sold the entire contents of his studio, it was the only painting he refused to part with.

3.

Models and Motifs

In 1900, Matisse was living in lodgings in the rue de Châteaudun, in the 9th arrondissement (near the boulevard de Clichy and the Gare Saint Lazare, the district bordering on Montmartre); the studio he rented was on the fifth floor of an apartment on the Left Bank, at 19, quai Saint Michel. By the time he turned thirty, on the eve of the new century, he had been married for two years to Amélie Parayre, the daughter of influential civil servants. Though Amélie was Matisse’s first wife, she had been preceded as the woman in his life by an artist’s model, Camille Joblaud, who had borne his first child, Marguerite, now five and a half years old. In the 1890s, Matisse and Camille, both in their twenties (she had been only nineteen when he met her as a student), had led a bohemian life among the cabarets and bars of Montmartre, until Camille became pregnant. She was forced in penury to give birth to Marguerite in the workhouse in the rue d’Assas, the district which smelled of ‘pommes frites and chloroform’, according to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who arrived in Paris two years later to write a monograph on Rodin. The workhouse birth was to haunt Camille’s dreams throughout her life. In the few years following it, however, Matisse enjoyed his first success as an artist when, in May 1896, the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts accepted five of his canvases for exhibition, including a portrait of Camille reading which had strongly appealed to popular taste. His luck had not lasted.

The portrait, Woman Reading, painted in delicate shades of bitumen and grey (inspired perhaps by the romanticism of Carrière), had seemed to set him on course as a successful painter; following the exhibition, it was purchased by the State. The following summer, Matisse made a visit to Kervilahouen, in Brittany. There he met artist John Peter Russell, an Australian Impressionist who painted with great verve in a style all his own but inspired by Monet and van Gogh. Russell introduced Matisse to the expressive possibilities of colour; when the Frenchman returned to Paris his viewers looked on aghast as work they judged crude and garish emerged from the painter whose subtle shades of grey had seemed so soothing on the eye. The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts disowned him. With a baby to feed, Camille did everything she could to persuade him to return to his old, successful methods of painting in subtle pastels. She tried in vain. For Matisse, nothing was more important than the development of his new ideas as a colourist, though, since his experiences among the workers of Montmartre, he would never have been satisfied with depicting colourful, leisurely riverside scenes. For the time being, his focus was all on his experimentation with colour. Already, like Derain, he was ready to depart from the ‘natural’ palette of Impressionism, wanting to explore a more subjective interpretation of his subjects. Camille remained unconvinced. Under the strain of his apparent disintegration as a painter, their relationship broke down. She no longer felt able to express unequivocal support for his work.

Matisse’s first encounter with Amélie Parayre, at a wedding in 1897, was the start of a whirlwind romance. They married three months later and, with her generous dowry, began their honeymoon in London, where Matisse first saw Turner’s paintings, in the National Gallery. Afterwards they travelled to Corsica, where the intense, natural colours of the landscape, the sultry heat and the heady, herbal scents of the foliage had the effect of releasing in Matisse a surge of creative energy. Colours were different here, intensified by the strong deep-blue and coral-toned light, a revelation to the man brought up in Le Nord with its pale, sea-blue skies above the textile factories of his home town of Bohain. Throughout his youth he had endured long, hard winters in a place where the workers’ habits of self-discipline and self-denial were merely strategies for survival. In Corsica, with his new wife, his passion for his work was allowed to blossom and his fascination with colour, and with the virtuosity and texture of paint itself, continued to grow.

Amélie, practical and level-headed as well as staunchly loyal, understood from the start the need to nurture her artist husband’s evident talent, and she was prepared to devote her life to creating the conditions he needed to pursue his work. When they returned to Paris, she took his illegitimate daughter, Marguerite, under her wing, an unusual act of devotion and generosity, given the conventions of the time. She understood, too, Matisse’s lapses into extravagance. He was lured first by a pressed butterfly he found in a shop on the rue de Rivoli, for which he parted with fifty francs (half his monthly allowance from his father), unable to resist the beauty of its sulphur-blue wings. The second was a painting which he purchased one day in 1899 from Ambroise Vollard, a dealer with a small gallery in the rue Laffitte – a justifiable expenditure, surely, since the picture was by Cézanne. After some determined haggling, he acquired Three Bathers for 1,600 francs (clearly a triumph for Vollard, since he generously threw in a plaster bust by Rodin). Amélie made no objection; on the contrary, she helped by pawning her emerald ring, a wedding gift from her parents’ employers, and uncomplainingly mourned the loss of it when Matisse finally returned to the pawn shop only to discover the ticket had expired.

By 1900, Matisse and Amélie were expecting their second child. (Their son Jean had been born in 1899; Pierre was due the following June.) Despite his personal happiness, Matisse was anxious, for his prospects as an artist were still bleak. He now found himself, to all intents and purposes, back at the beginning of his career. When he left Jambon’s, he had had no income and no prospect of further success in the art world. Now, a young family of five was relying for its survival on Amélie’s job as a modiste (a salesgirl who also modelled the wares) in her aunt Nine’s hat shop on one of the grand boulevards, until her parents’ employers set her up in a small hat shop of her own.

In the evenings, while Amélie looked after the children, Matisse went out to earn the few extra sous they badly needed, sketching in the cabarets and bars at the foot of the hillside of Montmartre, in the Cirque Medrano or the Moulin Rouge, or up at the top of the Butte in the popular windmill-turned-dance hall, the Moulin de la Galette (just a few paces from where Picasso was living in Nonell’s studio in the rue Gabrielle). Here, back in 1876, Renoir had painted the local girls dancing outside in the sunlight. The place had changed since those days; there was now a large indoor dance hall, gaslit in the evenings. The light reflected off the green distempered walls, creating the effect of a mirror. There were palm trees in the corners, plenty of space for dancing and a platform for the orchestra, but artists still went up there to sketch. Van Dongen was often seen there.

Van Dongen had been in Paris for three years, mainly occupied with his daytime work as an illustrator for the satirical magazine L’Assiette au beurre. In the evenings, he sat sketching in a corner of the Moulin de la Galette, smoking his clay pipe. In his navy-blue fisherman’s jersey and leather sandals, he was the only person in the place in casual dress; since the refurbishment, hats for the dancers were de rigueur. By 1900, the artists who sketched there included newcomer Pablo Picasso, though meeting either Ma-tisse or van Dongen (who became a close friend when Picasso found him a studio in the same building as his own) had yet to happen. In the foreground of Au Moulin de la Galette, painted by Picasso in autumn 1900, women with rouged lips sit at tables, leaning in, exuding sensuality; behind them, the forms of dancers merge indistinctly into the general atmosphere of vitality and warm colour. His painting of the old dance hall announces the beginnings of a radical new vision; nuanced forms are subtly melded, backlit in mellow, rose tones by a row of soft-glowing gaslights.

• • •

By the end of their first day in Paris, Picasso and Casagemas had already hired a model and begun painting in Nonell’s studio. The next day, they met their Catalan friends in a café, where Picasso began to sketch the locals, who clearly failed to live up to the standards set by the patrons of Els Quatre Gats. The cafés of Paris seemed full of ‘pompous bachelors . . . None of them can compete with the serious way we discuss people . . .’ Instead, they went to the Théâtre Montmartre, where they saw a horror show – ‘lots of deaths, shootings, conflagrations, beheadings, thefts, rapes of maidens . . .’ There was little to stimulate them in the cafés.

In the 1890s, the artists, writers and intellectuals of Montmartre had gathered in the Chat Noir at the foot of the Butte, where the waiters dressed as academicians and the editorial staff of La Revue blanche mingled with celebrated artists of the Belle Époque. The place had, however, closed in 1897 and, by 1900, anyone seeking an intellectual conversation tended to head for the cafés and bars of haute Montmartre, their territory bounded on the right by the rue Lepic, on the left by the rue Lamarck. You had to know which café to patronize; and, at the turn of the century, the intellectual ambience was still predominantly satirical, as reflected in the small-circulation magazines L’Assiette au beurre, La Vie parisienne and Le Rire, which provided lucrative work for any skilled artist prepared to turn his hand to caricature.

Like Matisse and van Dongen, for the time being, Picasso and Casagemas found more to entertain them in the Moulin de la Galette. And, despite his initial reluctance, Picasso soon found his way to the foot of the Butte, where the atmosphere of the cabarets – the Moulin Rouge, the Folies Bergère, and the Divan Japonais, where Jane Avril used to dance – was very different. If the nightlife here had initially seemed tawdry and prohibitively expensive, it nevertheless soon exerted its allure. In any case, it was not really necessary to enter the boîtes, since their mood spilled out on to the streets. Wine was tax-free throughout Montmartre – another reason why the bohemian lifestyle of the district had succeeded in setting the tone of the French capital; there was more Montmartre in Paris, people said, than Paris in Montmartre.

At the foot of the Butte, along the boulevard Rochechouart, the whores with painted faces strolled through the streets, their hair dyed blue-black, as though the streets of Montmartre were just another theatrical stage. In the bars, they sat waiting over a drink or leaning on their elbows, head in hands, blatantly unchaperoned. Picasso celebrated them in paintings smouldering with seductive sensuality. The women of Montmartre fascinated him, this nineteen-year-old boy from Spain, where devout women wore their lace mantillas and the whores plied their trade behind firmly closed doors. His paintings of autumn 1900 seem to give off the scents of musk and patchouli oil, the chatter of the crowd, the hum of accordion music; all the sensual heat of the streets. The works he painted that autumn are moody, visceral descriptions of the low life of Montmartre, paintings such as L’Attente and The Absinthe Drinker, in which the human form becomes vivid, colourful, subtly exaggerated. In L’Attente, colour itself seems to create perfume and warmth, the curves of the female form strongly modelled in shades of auburn against a background of shimmering yellow, the eyes of the sitter outlined in complementary blue, reflected in the tones of her hand. The streets of Paris had already exerted the intoxicating allure of new subjects; this was oil painting as it had never been seen before. And Picasso must have found the money to go to the cabarets occasionally, since he also made pastel sketches of singers onstage, in yellow or emerald-green dresses, their arms dusted with rice powder. These were small, delicate works, beautifully drawn, with titles such as La Diseuse and The Final Number. Like Matisse, he must have stood in the streets to sketch, as he also made drawings of the theatregoers on their way into the Opéra, the coachmen waiting for them to come spilling out, capturing all the glamour of the theatre.

One of the Catalans in Picasso’s circle was thirty-year-old Père Mañach, son of a Barcelona safe and lock manufacturer, a fashionable anarchist and natural networker with considerable artistic judgement. He had set himself up, albeit modestly, as a dealer in modern Spanish art, principally by getting to know Berthe Weill, an American born in Paris, dealer of rare books and antiques, whose scraped-back hair and distinctive pince-nez gave her the look of a schoolteacher. She had just opened her first art gallery, at 25, rue Victor-Massé, where she had already exhibited work by some of the young Spanish artists around Montmartre. (Degas, who still lived in the street, disdainfully ignored her, though she was far from undiscerning; some years later, in 1917, she organized the only ever solo exhibition of Modigliani’s work to take place in his lifetime.) She now agreed to take on a few works by Picasso, including Au Moulin de la Galette, which she sold immediately. Soon afterwards, Mañach arrived in Nonell’s studio, bringing with him the Spanish consul, who also bought a painting by Picasso, The Blue Dancer. On the strength of the painter’s obvious prospects, Mañach offered him a contract: the Spaniard would pay him 150 francs a month to represent his work in Paris. He then went to see Ambroise Vollard, the dealer in the rue Laffitte who had sold Matisse Three Bathers by Cézanne. Mañach had an entrée to Vollard through a friend, a manufacturer in Barcelona who had made Vollard’s acquaintance in Spain. The dealer remembered the encounter, since he had been invited to visit the factory, where a lamp burned at the entrance to the workshops before the statue of a saint. ‘The workmen pay for the oil,’ Mañach’s friend had told him. ‘So long as the little lamp is burning, I am safe from a strike.’

Picasso worked intensively for the best part of the next two months, producing pictures for Mañach to show Vollard, at the end of which he had amassed plenty of sketches of the street life and characters of Montmartre. However, by December, life in Nonell’s studio was already beginning to pall. Casagemas was hopelessly in love with a beautiful Montmartroise, a model called Gabrielle who persistently refused to marry him. He was becoming desperate, and beginning to disrupt Picasso’s work with his bouts of depression. Christmas was coming; perhaps they should go home to see their families. Maybe a return to Barcelona, and a break from Gabrielle, would bring Casagemas to his senses. Mañach was still waiting for paintings, but the sketches could probably be worked up into paintings just as well there as in Paris. A day or two before Christmas, the two returned to Barcelona.

4.

The Picture Sellers

When Mañach offered to handle Picasso’s work and Vollard sold Matisse a painting by Cézanne, most of the marchands de tableaux in Montmartre were still hardly more than pedlars of bric-a-brac; they sold paintings along with old furniture and miscellaneous junk. If they came upon a painting they thought was valuable, it might be stowed in a cupboard, away from prying eyes. Others accepted paintings in return for payment and redeemed them later, the galleries acting as pawn shops to painters who were down on their luck. The picture sellers were all clustered in the same area of Montmartre, between the rue Laffitte (where, at the far end, the sellers of more traditional paintings and objets d’art kept their shops) and the foot of the Butte. Few of them ever became successful or well known, though their names were at the time familiar throughout the neighbourhood. Portier had a mezzanine in the rue Lepic; Père Martin kept a miserable little place in the rue des Martyrs, but it was well stacked with magnificent paintings – at least, so the rumour went. In the early days, he had bought Renoir’s La Loge for 485 francs (his rent was overdue; that was the sum he owed). Who knew what else he might turn up?

Rumours of significant discoveries quickly circulated and every-one was always on the lookout for a work by a celebrated artist, whether or not he had any real taste in or knowledge of painting. Soulier, like Martin, kept a bric-a-brac shop in the rue des Martyrs, where he sold old beds and other bits of cheap furniture, until he took to buying pictures; he would give the artist a few francs and throw in a drink. He had no aesthetic judgement whatsoever; he simply bought whatever was cheap – in those days, Rousseau, van Dongen, young Maurice Utrillo and, occasionally now, Picasso. Pictures became such a passion for Soulier that he gave up the bric-a-brac trade as a rising tide of canvases rose from the ground floor right up to his bedroom, forcing him to sleep in a hotel. Some shrewd dealer poking around his premises had on one occasion discovered a picture by Manet so, ever afterwards, Père Soulier was convinced that every painting he bought might prove to be another.

A character known as Bouco was regularly seen trailing through the streets of Paris with a donkey cart, calling, ‘Pictures! Frames!’ When Soulier died suddenly of illnesses brought on by alcoholism, Bouco bought his collection en bloc and carried it off to his home in Bicentre. No one ever knew what became of it. The sign outside the shop of Clovis Sagot – a former clown from the Cirque Fernando (now renamed the Medrano), who had turned an old pharmacy at 46, rue Laffitte into a gallery where he sold paintings and dispensed ‘cures’ mixed from potions left behind by the shop’s previous owner – read, ‘SPECULATORS! Buy art! What you pay 200 Francs for today will be worth 10,000 Francs in ten years’ time.’ Père Angely, known on the Butte as Léon – bald, fat, a retired solicitor’s clerk who was losing his sight – collected indiscriminately until, eventually, he had to sell the lot for as little as he had paid for it. He was rumoured to be the first ever purchaser of a Picasso, who afterwards somewhat uncharitably remarked that the only person who had seen the value of his work in those days had been blind. (Many years later, he once avowed that no one who looks at a painting really knows what he is seeing.)

There were also those with money to invest, professional dealers including the Bernheim-Jeune brothers (Josse and Gaston, sons of Alexandre Bernheim) and the fabulously rich Russian textile magnate Sergei Shchukin, regarded as an eccentric in his native Moscow, who had begun to collect contemporary Western art. (German dealers came in later in the decade; Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler opened his first small gallery in 1907.) For the time being, young artists desperately needed new outlets and, by mounting one-man exhibitions in their galleries, dealers were now, albeit on a small scale, beginning to provide them. One of their main supporters was Berthe Weill, but, though she actively encouraged these younger artists, her maternal approach never seemed to succeed in making any of them rich. It was at her gallery that Picasso had first met Mañach, to whom he now owed the prospect of the first exhibition of his work in Paris, since Mañach had eventually managed to persuade Ambroise Vollard to show it in his gallery in June.

Vollard was different from the other dealers. Neither a chancer nor, in those days, an established international figure in the art world, he had a shrewd eye for a painting and a passion for collecting. No one could ever be sure what he kept hidden away in his cupboards, accumulating value until he judged it timely to reveal it. He had opened his first boutique, at 37, rue Laffitte, back in 1893, a place with just a shop window, back room and bedroom. When he had the idea of exhibiting the work of a single artist, he was perhaps the first dealer to do so. His inaugural show was an exhibition of works from Manet’s studio; following that show, Mme Manet had introduced him to Renoir and to both Pissarros (Camille and his son Lucien). Between 1894 and 1897, Vollard dealt in the works of Manet, Renoir, Degas and Cézanne, and already by 1895 he was able to move to larger premises.

In April 1895, he moved to 39, rue Laffitte, where his new gallery was not the dark and gloomy cubbyhole people later remembered but actually (though memorably dusty) a sizeable place, with a mezzanine floor and large window, strategically placed near the fashionable boulevards so that, as he once pointed out, the ladies could go shopping for outfits while their husbands looked for a bargain work of art. While the rest of Paris was still admiring the paintings of the Belle Époque, Vollard celebrated the opening of his new premises by mounting the first exhibition in Paris of the works of van Gogh (loaned by the artist’s brother, Theo). That autumn, he mounted the first ever solo show of Cézanne’s work, comprising approximately a hundred and fifty pieces. He timed the exhibition to coincide with the wake of the Caillebotte legacy, when the State had just accepted Caillebotte’s gift of his Impressionist collection but had refused several works by Cézanne. Vollard chose one of the rejected paintings, Baigneurs au repos, to display in his window to advertise the exhibition. Outside on the pavement, a row broke out between a young Montmartrois and his fiancée, who was demanding to know why he had brought her here to look at such obscenities. If casual passers-by were easily shocked, however, the exhibition was greeted enthusiastically by Renoir, Degas and Monet, who understood that, in his final years, Cézanne still had a future as an artist. In 1899 (the year Matisse purchased Three Bathers), Vollard commissioned Cézanne to paint his portrait.

Since the works of the Impressionists had gone on display in the Musée du Luxembourg, the students at the academies had had an opportunity to study them. Though, generally, they admired them, they found them unchallenging; most were searching for ways of painting that would feel more iconoclastic, wanting to find methods of capturing the more radically political spirit of the turn of the century. In general, Cézanne’s work, with its emphasis on breaking forms, interested them more than that of Monet, Sisley or Pissarro. Although Matisse certainly admired, and gained from discovering, the work of the Impressionists, as a friend of his (writer Marcel Sembat) once put it, even Matisse was ‘never a real Impressionist. One couldn’t be any more, since Cézanne.’

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.