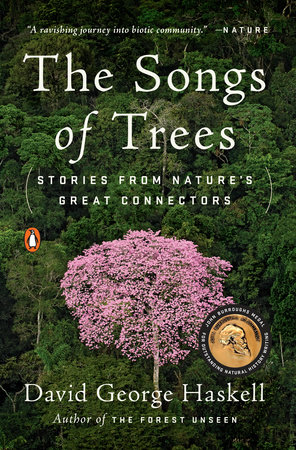

Ceibo Near the Tiputini River, Ecuador 0¡38'10.2" S, 76¡08'39.5" W Moss has taken flight, lifting itself on wings so thin that light barely notices as it passes through. The sun leaves not a color but a suggestion. Leaflets spread and the moss plants soar on long strands. A fibrous anchor tethers each flier to the swarm of fungi and algae that coats every tree branch. Unlike their crouched and bowed relatives in the rest of the world, these mosses live where water has no skin, no boundary. Here the air is water. Mosses grow like filamentous seaweeds in an open ocean.

The forest presses its mouth to every creature and exhales. We draw the breath: hot; odorous; almost mammalian, seeming to flow directly from the forest's blood to our lungs. Animate, intimate, suffocating. At noon the mosses are in flight, but we humans are supine, curled in the fecund belly of life's modern zenith. We're near the center of the Yasun’ Biosphere Reserve in western Ecuador. Around us grows sixteen thousand square kilometers of Amazonian forest in a national park, an ethnic reserve, and a buffer zone, connected across the Colombian and Peruvian borders to more forest that, seen through the lofty gaze of satellites, forms one of the largest green spots on the face of the Earth.

Rain. Every few hours, rain, speaking a language unique to this forest. Amazonian rain differs not just in the volume of what it has to tell-three and a half meters dropped every year, six times gray London's count-but in its vocabulary and syntax. Invisible spores and plant chemicals mist the air above the forest canopy. These aerosols are the seeds onto which water vapor coalesces, then swells. Every teaspoon of air here has a thousand or more of these particles, a haze ten times less dense than air away from the Amazon. Wherever people aggregate in significant numbers, we loose to the sky billions of particles from engines and chimneys. Like birds in a dust bath, the vigorous flapping of our industrial lives raises a fog. Each fleck of pollution, dusty mote of soil, or spore from a woodland is a potential raindrop. The Amazon forest is vast, and over much of its extent the air is mostly a product of the forest, not the activities of industrious birds. Winds sometimes bring pulses of dust from Africa or smog from a city, but mostly the Amazon speaks its own tongue. With fewer seeds and abundant water vapor, raindrops bloat to exceptional sizes. The rain falls in big syllables, phonemes unlike the clipped rain speech of most other landmasses.

We hear the rain not through silent falling water but in the many translations delivered by objects that the rain encounters. Like any language, especially one with so much to pour out and so many waiting interpreters, the sky's linguistic foundations are expressed in an exuberance of form: downpours turn tin roofs into sheets of screaming vibration; rain smatters onto the wings of hundreds of bats, each drop shattering, then falling into the river below the bats' skimming flight; heavy-misted clouds sag into treetops and dampen leaves without a drop falling, their touch producing the sound of an inked brush on a page.

The leaves of plants speak the rainÕs language with the most eloquence. Plant diversity here reaches levels unrivaled anywhere on Earth. Over six hundred species of tree live in one hectare, more than in all of North America. If we survey an adjacent hectare, we add yet more species to the list. Every time I have visited, my anchor in this botanical confusion and delight is a Ceiba pentandra tree, a species that many local people call ceibo, pronounced SAY-bo. Twenty-nine paces take me around its base, steps that circle buttress roots radiating from the center, each root starting head high at the trunk, then sloping down into the forest. The trunk is three meters across, wider by half than the columns that support the Parthenon. Despite its impressive size, the tree is not nearly so ancient as the pines, olives, and redwoods that live in cold or dry climates and count their years in millennia. In the fungus- and insect-filled Amazon, few ceibo live more than a couple of hundred years. Ecologists estimate that this tree is between 150 and 250 years old. The tree is large not because it is old but because young ceibo lance upward by two meters every year, sacrificing wood strength and chemical defenses for speed of growth. The ceiboÕs crown, its uppermost branches, form a wide dome that rises ten meters higher than the surrounding trees, themselves forty meters high, the equivalent of about ten stories in a human building. From a perch in the crown I see a forest canopy unlike that of relatively smooth-topped temperate forests. A dozen other ceibos grow between my eye and the horizon, each one a hummock protruding from the uneven, fissured surface created by the surrounding trees.

The tree is a giant. An axis mundi? Perhaps, but the rain's sound refutes any attempt to use a single idea to isolate the tree from its community. Every falling water drop is a tap against leafy drumskins. Botanical diversity is sonified, calling out under the drummer's beat. Every species has its rain sound, revealing the varied physicality of leaves of the ceibo tree and the many other species that live on and around its massive form.

The expansive leaflets of flying moss tick under the impact of a drop. An arum leaf, an elongate heart as long as my arm, gives a took took with undertones that linger as the surface dissipates its energy. The stiff dinner-plate leaves of a neighboring plant receive the rain with a tight snap, a spatter of metallic sparks. A rosette of lance-shaped leaves sprouts from the tip of a Clavija shrub, each leaf twitching as the rain smacks the surface. The sound is flat, tup, with none of the urgency of less yielding leaves. The leaf of an Amazonian avocado plant sounds a low, clean, woody thump.

These sounds come from the ceibo's understory plants, species that root themselves under the spreading branches and amid the duffy soil around the trunk. The water that strikes the understory has already passed across many leaves above. In the treetops most leaves have forms characteristic of the tropics: smooth surfaces ending in sharp tips or filaments. These "drip tips," combined with slick leaf surfaces, gather water, drawing it into large teardrops. As tears swell on the leaf tip, the water becomes a lens, refracting light so that an inverted image of the forest appears within. The drop has only a thin tip to hold, so every few seconds the leaf releases the accumulated water, then another lens bulges, flashing its image before falling away. The leaf thus sheds water, drying itself and slowing the growth of moisture-loving fungi and algae. These drip tips in the upper levels of the forest enlarge the already-giant raindrops, sending them down to understory plant skins. Larger leaves gather the most water and drip fastest, so the rhythms of the understory are born in the diversity of leaf shapes in the ceibo's crown. The myriad sizes, shapes, thicknesses, textures, and pliancies of the leaves below add texture to the sound. Even the litter sings with a vigor that I have not encountered elsewhere. This ground sound is the clack and tick of thousands of spring-wound clocks, each releasing its tension with a tschak unique to the woody muddle of the decomposing surface.

In the ceibo's crown, botanical acoustic diversity is present, but it is more subtle. Drops are smaller and create a sound like river rapids in the leaves of the many surrounding trees, obscuring variations in the sounds of individual leaves. Because I'm standing high up in the branches of an emergent tree, a tree that arches over all others, the sound of the river rapids comes from beneath my feet. I feel inverted, like an image in a teardrop, disoriented by hearing forest rain under my soles. My ascent, up a forty-meter series of metal ladders, has carried me through the rain layers: The sounds of rain on litter and understory plants fade a meter or two above the ground, replaced by the spare, irregular spat of drops on sparse leaves, stems reaching up to the light, and roots drilling down. At twenty meters up, the foliage thickens and the rapids begin. As I climb higher, the sounds of individual trees push forward, then recede, first a speed-typist's clatter from a strangler fig, then rasping drops glancing across hirsute vine leaves. I top the rapids' surface and the roar moves below me, unveiling patters on fleshy orchid leaves, greasy impacts on bromeliads, and low clacks on the elephant ears of Philodendron. Every tree surface is crowded with greenery; hundreds of plant species inhabit the ceibo's crown.

Human contrivances to keep away water are useless here and dull the ears. Rain jackets may repel falling drops, but their plastic magnifies the tropical heat and sweat soaks from within. Unlike many other forests, there is so much acoustic information revealed by the rain here that the crack, puff, or smack of drops on woven polyester, nylon, and cotton become an aural barrier and distraction. The yielding, lightly textured surface of human hair and skin is silent, or nearly so. My hands, shoulders, and face answer the rain with feeling, not sound.

When Western missionaries arrived here, they insisted that their colonized, evangelized subjects wear clothing. An unintended effect of this stricture was to reorient ears toward the self and away from the forest, partly closing the door to acoustic relationship with plants and animals. My conversations with members of the Waorani, the local indigenous culture, have almost without exception included unsolicited comments about the awkwardness and constraint of the clothes required when visiting town. The Waorani have lived in the forest for thousands of years, but outsiders now threaten their lives and culture. Clothes therefore weigh heavily for many reasons. I suspect that one of these is the disconnection from the acoustic community, a significant loss for people who live within multispecies relationships. Just as factory millworkers are deafened by machinery, given "cloth ears" by their work, wearers of the cloth itself also sometimes lose the ability to hear.

In the ceibo's crown, animal sounds overlay the plant rhythms: whine, murmur, howl, yelp, whistle, squeal, and whir. Every sonic verb has its champion, and many species communicate with sounds for which our language has no adequate descriptors. The blurred wings of a fork-tailed woodnymph hummingbird drone, a sound edged in whiplike squeaks. The bird, a thumb-size glint of iridescent blue and green, dips its beak into the red arch of flowers emerging from a zebra bromeliad. Between the bromeliad's fleshy pineapple-top leaves a frog calls ko-ko-ko-UP!, a jaunty song that awakens a call-and-response chorus from dozens of other frogs hidden in the thickets of bromeliads that cover the ceibo's branches. Unlike drip-tipped leaves, the erect rosettes of bromeliads collect and hold water. Each bromeliad can contain four liters in the gaps between the base of its leaves, a breeding site for frogs and hundreds of other species. One hectare of forest carries fifty thousand liters of water in treetop bromeliads, much of this volume pooled along branches of the large, emergent trees. The ceibo is a sky lake.

Water pools are not the only habitat in the crown. There are as many microclimates among these branches as exist within hundreds of hectares of most temperate forests. Bogs accumulate in sheltered crotches. Ephemeral wetlands fill and dry within knotholes. Dozens of years of leaf fall have accumulated in the ceibo crown, building soil as deep and rich as the litter on the ground. The soil lies on wide tree branches and is caught in tangles of vines. Rooted in this duff, a fig tree with a trunk as wide as a human torso grows amid half a dozen other trees in the confluence of ceibo branches, a forest rooted fifty meters above the ground. These trees cluster on the northern and eastern sides, where the crown's soil stays moist and the ceibo leaves grow thickest, like a shady forest ravine. On the exposed southwestern branches, a community of cacti, lichens, and razor-leaved bromeliads endure the alternation between deluge and desert, swelling in the rain, then crisping in the unobstructed equatorial sun. On vertical trunks, vines interweave with orchid gardens, creating water-holding mats in which ferns take root. Above all this grow the ceibo's own leaves, each one the size of a child's hand, fanning in eight or so elongate leaflets. The tree holds its leaves on twig tips, creating a gauzy haze. The leaves seem insubstantial for so large a tree, but unlike the sheltered plants below, these leaves must withstand the wind of thunderstorms and downbursts. Their small size and fanlike shape allow each leaf to fold up and yield to the wind.

Most tropical biologists have worked at ground level. But lately towers, rope ladders, and cranes have carried some scientists into the treetops. There they've found that as many as half, and perhaps many more, of the forests' species dwell in tree crowns and nowhere else. "Canopy," the biological term for the crowns of many tree species in a forest, is too simple a word for such a complex, three-dimensional world.

Maps of biological diversity give us another way to understand the many lives of this ceibo tree. When the richness of plants, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals-admittedly a mere subset of life's diversity, but the subset that we know best-is tallied across the world, a color-coded map of diversity reveals the places with the largest number of species in each group. The place where these maps converge, the glowing eye of the map, is eastern Ecuador and northern Peru, the western Amazon. Tabular ranking of categories of species within these larger taxonomic groupings confirms what the maps suggest. By most measures this is the modern apogee of terrestrial biodiversity, the result of life's creativity incubated in tropical heat and rain. Evolution has had time to elaborate its hothouse productions: the western Amazon has been a tropical forest for millions, perhaps tens of millions of years. The region's geologic history is poorly understood, but the western Amazon's location between the uplifting Andes and the shifting coastline of the Atlantic may have opened it to invasion by new species from sea and mountains, further leavening the rise of biodiversity.

A less formal but equally informative indicator of the diversity of this forest is a walk with a professional botanist, either a professor or an experienced forest guide. Their extraordinary biological and cultural knowledge encompasses all the more common plants, including the role of plants in the lives of humans. The experts also bring specialized understanding of the identities and stories of a particular subgroup, the plants that they have studied for decades. But the task of identifying the majority of species, let alone knowing the stories of these plants, is far beyond their grasp. Species unknown to and undescribed by Western science are all around. Botanists recently discovered one new species on the walkway to the dining hall at a biological research station. This forest is the place where biological hubris dies: we live in profound ignorance of the lives of our cousins.

Copyright © 2018 by David George Haskell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.