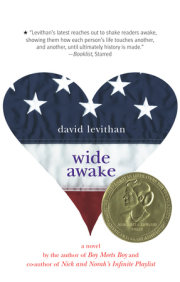

one

“I can’t believe there’s going to be a gay Jewish president.”

As my mother said this, she looked at my father, who was still staring at the screen. They were shocked, barely comprehending.

Me?

I sat there and beamed.

two

I think it was the Jesus Freaks who were the happiest the next day at school. Most of the morning papers were saying that Stein’s victory wouldn’t have been possible without the Jesus Revolution, and I don’t think Mandy or Janna or any of the other members of The God Squad would’ve argued. Mandy was wearing their jesus is love T-shirt, while Janna had a love thy neighbor button on her bag, right above the stein for president sticker. When they saw me walk through the door, they cheered and ran over, bouncing me into a jubilant hug. I wasn’t the only gay Jew they knew, but I was the one they knew best, and we’d all been volunteers on the Stein/Martinez campaign together. After the hugging was done, we stood there for a moment and looked at one another with utter astonishment. We’d done it. Even though we wouldn’t be able to vote for another two years, we’d helped to make this a reality. It was the most amazing feeling in the world, to know that something right had happened, and to know that it had happened not through luck or command but simply because enough people had understood it was right.

Some of our fellow students walked by us and smiled. Others scoffed or scowled--there were plenty of people in our school who would’ve been happy to shove our celebration into a locker and keep it there for four years.

“It was only by one state,” one of them grunted. “Only seventy-six thousand votes in Kansas.”

“Yeah, but who got the popular vote?” Mandy challenged.

The guy just spat on the ground and moved on.

“Did he really just spit?” Janna asked. “Ew.”

I was looking everywhere for Jimmy. As soon as the results had been announced, I’d gone to my room to call him.

“Can you believe it?” I’d asked.

“I am so so so happy,” he’d answered.

And I was so so so happy, too. Not only because of the election but because Jimmy was around to share it with. I had two things to believe in now, and in a way they felt related. After years of questioning whether the world was only going to get worse, I believed in the future, and in our future.

“I love you,” he’d said at the end of the call, his voice bleary from the hour but sweetened by the news.

“I love you, too,” I’d replied. “Good night.”

“A very good night.”

Now I wanted the continuation, the kiss that would seal it. Stein had triumphed, the electoral college was secure, and I was in love with a boy who was in love with me.

“Somewhere Jesus is smiling,” Janna said.

“Praise be,” Mandy chimed in.

Keisha and Mira joined us in the halls, fingers entwined. They looked beamy, too.

“Not a bad day for gay Jew boys, huh?” Keisha said to me.

“Not a bad day for Afro-Chinese lesbians, either,” I pointed out.

Keisha nodded. “You know it’s the truth.”

We had all skipped school the previous two days to get out the vote. Since most of us weren’t old enough to drive, we acted as dispatchers, fielding calls from Kennedy-conscious old-age-home residents and angry-enough agoraphobic liberals, making sure the buses came to take them to the polls. Other kids, like Jimmy, had been at the polling places themselves, getting water and food for people as they waited hours for their turn to vote. (Our state hadn’t made it illegal to give people water and food, like some other states.)

I felt that history was happening. Not like a natural disaster or New Year’s Eve. No, this was human-made history, and here I was, an infinitesimally small part of it. We all were.

Suddenly I felt two arms wrap around me from behind, the two palms coming to rest at the center of my chest. Two very familiar hands--the chewed-up fingernails, the dark skin a little darker at the knuckles, the wire-thin pinkie ring, the bright red watch. The bracelet with two beads on it, jade for him and agate for me. I wore one just like it.

I smiled then--the same way I smiled every time I saw Jimmy. Part of my happiness lived wherever he was.

“Beautiful day,” he said to me.

“Beautiful day,” I agreed, then turned in his arms to sanctify the morning with our this is real kiss.

The first bell rang. I still had to run to my locker before homeroom.

“Everything feels a little different today, doesn’t it?” Jimmy asked. We kissed again, then parted. But his words echoed with me. I was too young to remember when the Supreme Court upheld the rights of gay Americans, and all the weddings started happening. But I imagined that day felt a lot like today. I’d heard so many older people talk about it, about what it meant to know you had the same right as everyone else. I wasn’t alive when Obama was elected, either, and instead came to consciousness at a time when there was a bigot on the megaphone, dividing the country further and shoving us right into a pandemic. I spent sixth grade at home, barely learning and never seeing my friends. Even when the bigot with the megaphone lost his election, things didn’t get much better. We were still in a pandemic. People yelled at each other more and more, in no small part because they could yell from their bedrooms instead of having to actually leave the house to do it face to face. This past election was absolutely brutal. But the brutality of it was an issue itself, and I think finally enough people were like, This is not how we should be. Enough of us believed we had to unplug the hate machine before it destroyed us all.

I understood that now that Stein had won, he was likely to become more moderate to get along with Congress, especially since we’d only won by the margin of Kansas. But still . . . everything did feel a little different. Yes, the kids walking the halls around me were the same kids who’d been there yesterday. The books in my locker were piled just the way I’d left them. Mr. Farnsworth, my homeroom teacher, waited impatiently by his door, just like he always did. But it was like someone had upped the wattage of all the lights by a dozen watts. Someone had made the air two shades easier to breathe.

I knew this feeling wouldn’t last. As soon as I realized it was euphoria, I knew it couldn’t last. I couldn’t even hold on to it. I could only ride within it as far as it would carry me.

The second bell rang. I sprinted into class, and Mr. Farnsworth closed the door.

“I expect to see you standing today,” he said to me.

This was the deal we had: If Stein won the Presidency, I would stand for the Pledge of Allegiance for the first time since elementary school. Even back then, I hated the way it seemed to be something rote and indoctrinated--most people saying the words emptily, without understanding them. To me, the whole notion that we had to pledge allegiance seemed antithetical to the notion of freedom of speech. Mr. Farnsworth told me that the whole “project of America” was about navigating seeming contradictions--in this case, finding a way to show allegiance to the idea of freedom without it imposing on that freedom.

“It’s called a pledge,” he said, “but the most important part is that nobody’s keeping track of who pledges and who doesn’t. It’s American to recite it, but it’s also crucially American for it to be voluntary.”

Even when I wasn’t making the whole pledge, I’d always said the six last words, because they were the ones I believe in, more than the concept of indivisibility. Today I said them extra loud, standing up.

With liberty and justice for all.

When I went to sit down, I found that my chair wasn’t there. I landed butt-first on the floor.

“What’s the matter, Duncan?” Jesse Marin’s voice taunted. “Forgot where you belong?”

There was some laughter, but most of it was Jesse’s. He cracked himself up on a regular basis.

He clearly hadn’t interpreted the election as an unplugging of the hate machine. Because for some people, the hate machine was like a fossil fuel--they couldn’t imagine having any power without it.

“That’s how it goes,” Jesse went on. “You stand up for something, you end up falling down on your ass.”

Jesse’s parents were big Decents in our town, and like most Decents he wasn’t taking defeat very well. You would’ve thought he’d be used to it now, with all the changes that had happened as the pandemic recovery began. With each step away from hate and division, the Decents had sworn it meant the demise of civilization. But, of course, civilization did okay without the Decents proclaiming what needed to be censored and who needed to be “protected.” They’d been smart at first--labeling everyone who wasn’t a Decent as indecent. The initial reaction to that was to say “No, I’m not indecent!” or “What I’m doing is not indecent!”--which immediately put us on the defensive. It was only when we could say “Actually, I’m decent and you have no right to call me otherwise” that changes began.

Love is more decent than hate.

Community is more decent than conflict.

Kindness is more decent than violence.

These were our tenets. This was our pushback. They tried to bind our rights with unsupportable laws. They tried to stoke fear of trans people and people of color, hoping to energize the declining white, cis minority. They tried to alienate parents from the educational system so they could impose their own system and educate people to be like them and depend on their products. They tried to garble the voting process as much as they could, thinking we’d shy away, that we’d be lazy when our lives were at stake. We fought in order to stop fighting. We got, tenuously, to the bare minimum of where we needed to be.

The Decents didn’t even call themselves “the Decents” anymore. We’d won back the word, just as we’d won back words like moral and right and compassionate. Because words mattered. Winning the words was a good part of the battle. And we won them by defining them correctly.

The principal’s voice came over the speakers and read the morning announcements. He made no mention of the election; to him, the only part of the future worth noting was the Conservation Club’s bake sale next Thursday and the football team’s game against Voorhees on Saturday. School is its own country, he seemed to be saying in all that he wasn’t saying. I am the leader here, and I am not subject to any election. What happens in the world at large remains at large while you are here.

I wanted to say something back to Jesse, to gloat or to cut him down. But then I thought of what Janna and Mandy would do, and I decided that I couldn’t let winning make me any less kind.

I could see Mr. Farnsworth keeping watch over me, wondering what I was going to do. When the bell rang, I made eye contact with him and received a small, approving nod. Then, as I was about to pass by his desk, he asked me to stay back for a second.

Once the other students had gone, he said, “If I’m not mistaken, you’re in Mr. Davis’s first-period class.”

I nodded.

“Look, Duncan, be careful today. He’s not taking this well. He wants to detonate on someone--don’t let it be you.”

I looked at Mr. Farnsworth. I knew nothing about his life--where he lived, how he voted, who he loved. But I could see he was genuinely worried. For me, yes. But for something bigger, too.

“I’ll be careful,” I promised.

And then I headed to Mr. Davis’s class.

three

The plus about Mr. Davis’s class: Jimmy was in it.

The minus: Mr. Davis was in it, too.

Both Jimmy and I had tried to switch out, but it was the only history class available first period. At the start, in September, Mr. Davis had been bad enough--he still held on to the idea that, say, the Indigenous population got a great deal when the Pilgrims came over, and that the word savage was acceptable to use in a history class, as if killing someone with an arrow was somehow more horrible than doing it with a gun or a bomb. Jimmy and I figured we could get through it because other teachers had already told us the truth, not just the Thanksgiving version. But then, as the election heated up, Mr. Davis seemed to forget he was teaching history and started lecturing us on current events instead. At one point, he let it slip to our class that he was an Iraq War Re-enactor, which disturbed me so much that I went to my guidance counselor and complained. I’d read in magazines about what Iraq War Re-enactors did--the “interrogations,” the simulated rescues, the ill-equipped soldiers facing ambushes, the falsified evidence--and I didn’t want to have anything to do with a teacher involved in such things. My guidance counselor understood, but explained about needing the history class and promised she would have a talk with Mr. Davis about not making inappropriate statements. This was, of course, the last thing I wanted her to do--but she did it anyway, and soon Mr. Davis was railing into “the Steinheads” even more.

To Mr. Davis, the three worst things that had ever happened were:

1) The Jesus Revolution

2) Stein’s candidacy

3) The concept of equality

because

1) Saying Jesus would be kind and loving instead of vengeful and violent didn’t fit into Mr. Davis’s plans.

2) Two words: Gay. Jewish. Although he’d never say it in only two words.

3) Every time another group became equal to straight cis white guys, it made Mr. Davis feel like he had that much less power . . . when the truth was that he never should’ve had so much power in the first place.

In choosing the three worst things that had ever happened, he conveniently forgot (among other things) the fundamental fact that our country was built on brutally stolen land using brutally stolen labor, and that this fact would never be justifiable. Like most countries, America was good at substituting mythology when history was inconvenient. Mr. Davis preferred to be a mythology teacher.

Copyright © 2024 by David Levithan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.