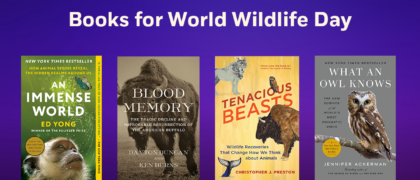

OneMaking Sense of OwlsUnpacking the Mysteries

Owls are probably the most distinctive order of birds in the world, with their upright bodies, big round heads, and enormous front-facing eyes-hard to mistake for any other creature. Even a young child has little trouble identifying them. The same is true for a range of species, including other birds-chickadees and titmice, ravens and crows-which can spot the shape of an owl instantly and single it out as an enemy. But beyond the basics of that telltale form, what makes an owl an owl? And how did these extraordinary birds get to be the way they are?

Through research on owls past and present, scientists are tracing these birds back to their earliest beginnings to make sense of their evolution and their family tree. Owls first appeared on earth during the Paleocene epoch, some fifty-five to sixty-five million years ago. Tens of millions of years later, they split into two families, Tytonidae (barn owls) and Strigidae (all other owls). Like all birds, they initially arose from a group of small, mostly predatory, running dinosaurs that were coexisting with other, larger dinosaurs sixty-six million years ago. That all changed when an enormous asteroid struck earth, triggering the mass extinction that killed off most of the big land-based dinosaurs. A few of the bird ancestors survived, including the forerunners of today's owls and all other living bird species.

As a group, owls were initially thought to be related to falcons and hawks because they shared a hunting lifestyle like these raptors. Later, they were lumped with nocturnal birds such as nightjars on account of their big eyes and camouflaged plumage. But new research shows that owls are most closely related not to falcons or nightjars but to a group of day-active birds that includes toucans, trogons, hoopoes, hornbills, woodpeckers, kingfishers, and bee-eaters. Owls probably diverged from this sister group during the Paleocene, after most of the dinosaurs died off and small mammals diversified. Some of those little mammals took to night niches, and owls adapted, evolving a suite of traits to take advantage of the nocturnal feast. Now most owls share an array of remarkable features that distinguish them from other birds and give them a unique ability to hunt at night, including retinas rich in cells that provide good vision in dim light, superior hearing, and soft, camouflaged feathers tailored for quiet flight. Of the 11,000 or so species of birds alive today, only 3 percent have these sorts of adaptations that allow for stalking prey in the dark.

Since their first appearance on the planet, about a hundred owl species have come and gone, leaving fossil traces of their existence, including

Primoptynx, a peculiar owl that soared across Wyoming skies fifty-five million years ago and hunted more like a hawk than an owl, and the Andros Island Barn Owl, a full three feet tall, which terrorized Pleistocene mammals. One extinct owl that vanished from the Indian Ocean island of Rodrigues relatively recently, in the eighteenth century, had a smaller brain than most present-day owls but a well-developed olfactory sense, suggesting it may have used its nose more for hunting and perhaps even scavenging.

Some 260 species of owls exist today, and that number is growing. They live in every kind of habitat on almost every continent-from desert and grassland to tropical forest, mountain slopes, the snowy tundra of the Arctic-and they range widely in size, appearance, and behavior, from the diminutive Elf Owl, a little nugget of a bird, impish, troll-like, about the size of a small pine cone and the weight of eight stacked nickels, to the massive Eurasian Eagle Owl, which can take a young deer; from the delicate Northern Saw-whet Owl that "flies like a big soft moth," as Mary Oliver wrote, to the comical, slim-legged Burrowing Owl, with its bobbing salute. There are Chocolate Boobooks and Bare-legged Owls, Powerful Owls and Fearful Owls (named for their bloodcurdling, humanlike scream repeated every ten seconds), White-chinned Owls and Tawny-browed Owls, Vermiculated Screech Owls and Verreaux's Eagle Owls, Africa's biggest, with its startling pink eyelids. Some owls, like the ubiquitous barn owls that occur in multiple forms worldwide, carry a raft of common names reflective of their mythic power: demon owl, ghost owl, death owl, night owl, church owl, cave owl, stone owl, hobgoblin owl, dobby owl, monkey-faced owl, silver owl, and golden owl.

Much to the amazement of researchers, new owl species are still turning up, including an owl that stunned scientists when it was discovered high in the Andean mountains of northern Peru. The Long-whiskered Owlet, a tiny, bizarre owl-one of the rarest birds in the world-with long wispy facial whiskers and stubby wings, is so different from other owls that scientists put it in its own genus, Xenoglaux, which means "strange owl" in Greek. It sings a rapid song described as "low, gruff, muffled

whOOo or

hurr notes" and is found only in high forests between two rivers in the Andes. In 2022, scientists discovered a new species of scops owl on the island of Príncipe, off the west coast of Africa, named

Otus bikeglia for the park ranger who was instrumental in bringing it to light. Because some owls live in isolated regions like these, in tropical rainforests and on mountains and islands where populations separated geographically can diverge genetically, the number of species may continue to climb.

Also boosting the species count and shifting the owl family tree is a deeper understanding of already recognized owl species. By closely examining the body structures, vocalizations, and DNA of known owl species, scientists are finding sufficient differences between populations to split one species into two or more.

Take barn owls. The oldest lineage of owls, barn owls probably first arose in Australia or Africa, spread through the Old World, and now live on nearly every continent. Because they look alike over their entire range, they were once classified as a single species. But owls are showing us that appearances can be deceiving. DNA studies have revealed that Tytonidae, the scientific name for barn owls, is in fact a rich complex of at least three species, with a total of some twenty-nine subspecies. And there may be others existing in remote places that haven't yet been recognized. Likewise, researchers recently used genetics to tease apart two new screech owl species from Brazil that had been grouped with other South American species: the Alagoas Screech Owl of the Atlantic rainforest, and the Xingu Screech Owl found in the Amazon. Both owls are threatened by deforestation and are at risk of extinction.

Along with new species, a flock of new insights on the nature of owls has flowed from laboratories and field studies around the world in the past decade or so, shedding light on a profusion of owl mysteries. Why are these discoveries emerging now? How are scientists making sense of the hidden lives and habits of these inscrutable birds?

For one thing, there are innovative new tools for studying the evolution, anatomy, and biology of owls and for finding them in the wild, tracking their movements, and monitoring their behavior. Cutting-edge imaging technology such as X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanning allows researchers to see inside the bodies of living owls, visualizing the anatomical structures that relate directly to behavior, and to peer through rock to see into fossils. DNA analysis is revealing relationships in the owl tree of life, challenging old concepts about who is related to whom and how closely. New "eyes" in the field-infrared cameras and other night vision equipment, radio tagging, and drones over areas as remote as the snowy landscapes of Siberia-are advancing new discoveries about owl behavior or confirming older observations by banders and biologists who have been in the field for decades. Satellite telemetry is illuminating the movements of owls over short and long distances. Tiny satellite transmitters packed onto the backs of Snowy Owls, for instance, are revealing wondrous new insights on their mysterious movements, such as the puzzling northward journeys of some of these iconic birds in the dead of winter.

Nest cams are offering a look at intimate owl interactions at the nest that would otherwise be impossible to observe: the feeding of mates and young, for instance, and the squabbling between siblings. "Nest cams tell all," says ornithologist Rob Bierregaard, who studies Barred Owls. "They offer the best picture of what's for dinner-flying squirrels, cardinals, salamanders, fish, crayfish, big insects-and how the feeding goes. You can see the male handing over food to the female to feed the young. I've seen males stash mice on branches and possum, too, delivering it piece by piece." Nest cams expose the sometimes nasty, sometimes charitable dynamics between siblings. Chicks in a brood can be selfish and competitive, to the point of siblicide. But some owlets display a remarkable form of altruism rare in the animal world. Nestling barn owls, for instance, are known to give food over to their younger siblings, on average twice per night.

Biologist Dave Oleyar pursued his master's research in the late 1990s and says he wishes he had had today's technology back then. "It's amazing what we can do now," he says. "Running these nest cams 24-7 and documenting prey deliveries to the nest, what the parents are bringing in and how often, we can gather a huge amount of data about their foraging patterns. Before we had these 'eyes' in the field, the logistical challenges of studying nestling growth, development, and interactions were overwhelming and limiting."

Listening to owls remotely with sophisticated new audio recording devices has been a boon to owl research, helping scientists understand the interplay of different owl species without disturbing them. With acoustic monitoring, for instance, researchers are sorting out the dynamics between Barred Owls and endangered California Spotted Owls of the Sierra Nevada. In placing audio recorders in close to a thousand locations across 2,300 square miles of mountainous terrain to collect owl calls, they have discovered completely unexpected interactions between the aggressive Barred Owls, on the one hand, and the smaller, but still surprisingly feisty spotted owls, on the other-with significant implications for conservation.

Another unusual new method for surveying and monitoring owls is distinctly less high tech and more nose heavy. Researchers are harnessing the olfactory powers of dogs to locate elusive owl species in places as far-flung as Tasmania and the Pacific Northwest. Specially trained "sniffer" dogs snuffle the pellets, those misshapen cigars made of leftover bits of undigested fur and bone, which owls eject onto the ground beneath their roosts and nests. The pellets are hard to spot, but they emit odors so the dogs can easily sniff them out, leading a researcher straight to the spots where the owls hang out.

Many breakthroughs have also come from more traditional ways of studying owls; trapping, measuring, and banding them-and monitoring the birds over long periods of time. Long-term study of owls in the wild is slow, hard work in all weathers, season after season, year after year, but it's yielding vital new windows on breeding behavior and population trends. Decades-long studies of Long-eared Owls, Burrowing Owls, Snowy Owls, and Tawny Owls are revealing how owls are responding to habitat loss and climate change, pointing us toward avenues for conservation, not just of owls but of whole ecosystems.

Making sense of owls means witnessing them in the wild, in their natural habitat. But while owls may be easy to recognize, they’re not easy to see, even for the experts. They often hide right under our noses in the day, camouflaged against the bark of trees or tucked into hollows, and in the night, sail off into the darkness, unobserved. “Finding owls is hard,” says David Lindo, a naturalist, photographer, and highly experienced bird guide known as the Urban Birder, who is forever on the lookout for birds. “It’s often a question of diligence. You have to commit yourself to it. You have to try and work out where they are and then religiously search the trees, look for pellets and splashback [the feces of owls, also known as whitewash].”

This is why the sophisticated new tools for owl detection and monitoring are so vital. But even with these powerful technologies, locating owls in the wild is still often a maddening and elusive treasure hunt. As Sergio Cordoba Cordoba, an ornithologist studying neotropical owls, told me, "It can be really frustrating. Technology is a great ally, infrared cameras and telemetry, but we often still rely on sounds. Trying to find an owl you hear singing is like being an explorer of old times. You try to follow the sound, walk or crawl to get nearer without making any noise (almost impossible with dry leaves on the forest floor), and when you think you are near enough, switch on the flashlight and see who is singing. Most times, I flush the owner and never find out who it is!"

Researchers and birdwatchers often attract owls with "playback," using audio recordings of owl territorial or mating calls to draw them in. "A guide may play the call of a particular species, like a screech owl," as Lindo explains, "and then five minutes later, one pops up in the tree, you flash a torch, take a picture, and then it's gone." I had the thrill of seeing a family of Striped Owls and two species of neotropical screech owls in southeastern Brazil using this method. It's an important tool for researchers. But as Lindo says, for the casual birdwatcher, "it's a bit of a cheat" and can disrupt the owls' natural behaviors.

Nothing beats a chance encounter, happening across an owl in the wild. People who understand the privilege of stillness and just sit, look, and listen-like owls themselves-sometimes get lucky. One of Lindo's most memorable owl moments came about this way. Some years ago, he was leading a bird tour in Helsinki, Finland. He had a day to himself, so he borrowed a bike from the hotel. "I noticed that there was a green area of woods near to me on an island," he told me. "So I cycled across a bridge to the island. I remember putting my bike down and just sitting in the forest. As I sat there, a Great Tit came really close to me. It landed on my cap, and then darted back up to the tree. It did this a couple of times, which puzzled me. Then I noticed something swoop across the clearing in front of me. It was a young Long-eared Owl, and it was hunting, totally unaware of me. I just sat there and watched it for maybe forty minutes, flying around, sometimes stopping very close to me. I kept stock-still. I was camouflaged by the trees, and it didn't notice me at all. That was an amazing moment."

Copyright © 2023 by Jennifer Ackerman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.