1

nomenclature Calla Paxson, now age seventeen, stood in the middle of their gravel driveway, nose down in her phone, trying very, very hard not to be distracted by her father, Dan, as he hurried back and forth from the shed to the pickup to the house and back again. Every time he went past, he had a new question for her—

“Is Marco coming?”

“Yes, Dad, Marco is coming, Jesus.”

Back and forth.

“What time is it again?”

“It’s nine a.m., Dad,” and as he went past, she added loudly, “aka

entirely too early, okay?”

Back and forth.

“Did Marco say he’d be here at nine?”

“Yes? No? I dunno, I’m not his boss, you are.”

Back and forth.

“You know, you could help me? Carry these—

oof—boxes?”

“That’s not really—like, not my thing.”

He eased the wooden crate of apples into the back of the pickup, but Calla wasn’t paying attention. She held her phone up, blocking the view of him. With the camera reversed, she checked herself in the screen—saw a thousand tiny flaws but steeled herself against caring about them. (Eyebrows too thin, ugh, mouth too wide,

ugh, left eye with that odd golden fleck hiding in the green, a green that wasn’t a pretty emerald but a muddy hazel the color of algal muck,

uggggh.) She chided herself for feeling that way.

Be better, say something nice about yourself, and she told herself today was a damn good hair day thanks to the humid September weather. She was all golden locks with the center part, framing her face with long layers, but the negative thoughts kept nagging her from the back of her mind. Calla shook the bad thoughts out of her head and (since Insta was over) checked her follower count on Faddish, then (since TikTok was almost over) checked her followers on Appy, then on Nextra, and of course also on Insta and TikTok because

obviously. The classics were the classics for a reason. Her follower counts hadn’t budged since this morning. Or since last night. Or the night before.

Gently, a hand reached out and eased the phone aside.

The same hand, her father’s hand, lifted her chin.

Her father stood there in front of her.

“It’s not your thing,” he repeated.

“What?”

“That’s what you just said. ‘That’s not really, like, my thing.’ ”

“Oh

god you’re about to give me a lecture, aren’t you?” She sighed. “I just mean I don’t know that I can move those boxes. They’re heavy. I already tried to clean myself up this morning and I don’t want to look like some

farm girl—”

“No lecture. I promise, Calla Lily. You’re right.

This is your thing.” He did a faux-game-show gesture toward her phone.

“I feel like you’re being sarcastic right now.”

“No sarcasm! I’m saying you wanna be a—what’s it called? An affluent—”

“Influencer. Jesus, Dad.”

“An

influencer.” He smiled. He was f***ing with her, wasn’t he? Was he f***ing with her or was he just this goofy? “Right. So I need your influence.”

She winced. “What?”

He did this awkward moonwalk toward the truck, and then did an even-cringier spin, snatching up one of the apples from the crate resting on the pickup truck’s open gate. Dance-walking his way back, he thrust the apple at her.

“I told you I’m not eating one, apples are gross,” she said.

Dan Paxson put his hand over his chest and feigned injury. “You hurt me. You know that, right? My own daughter

still won’t try my apple. My pride and joy insults my other pride and joy. It’s like my children are fighting. Sibling rivalry.”

“So dramatic.”

“I don’t need you to try the apple, but the apple needs your . . . influence. You know what I mean?”

She confessed: “I don’t.”

Her father sighed.

“Look, this is our first day at market. It’s not just tables and produce anymore. You’re right, it’s not enough to be the farmer anymore. People go there to sell their . . . fancy puddings and their honeycombs, it’s all pasture-raised beef and duck eggs. It’s produce you’ve never heard of like

mizuna and

kabocha and

micro-cilantro. And though I know this apple is beautiful with a taste that’s—” The words seemed to catch in his mouth. Was he getting emotional? He probably was, the big dork. (She loved her father’s profound dorkiness. He was such a nerd because he cared so much about this stuff. She wouldn’t admit any of this, not for a million followers on social.

Maybe for two million.) “I need help selling it.”

“That’s not what I do.”

Or what I want to do. “But you do. I see how much you put into your videos. You want people to . . . love the things that you love, and I love that about you. Maybe you could sprinkle a little of that pizzazz on this apple? Though I think there’s an actual apple named Pazazz, come to think of it.” He shrugged. “I’m just saying, you’re my little branding genius, you have these explosive, firecracker thoughts, and I think this apple is really something special. Like you. But nobody will know if they don’t try it. I need your magic, Calla Lily. I need your

sparkle.”

She rolled her eyes (trying to hide that, ugh, it felt

nice when he said nice things about her). “

Fine, I’ll give a glow up to your

dire little fruit.” And it was dire. Pretty, maybe. Gothy, definitely. In the sun, it was a rich, black-blooded red.

But she couldn’t say any of that. Gothy, black, red. It wasn’t a Hot Topic apple. It did need something. “Does it have a name already?”

He hesitated. Acting a little cagey.

“I gave it a name. It—” He flinched. “Didn’t have one before.”

“Okay, fine, what did you name it?”

Her father shrugged, like,

Oh, no big deal, don’t mind me. “I’m calling it the Paxson apple. After us. Our family. Our home.”

“Really. The Paxson.”

“Yeah. Why? Apples are—you know, the heirlooms, anyway, they’re named after the people who grew them. Baldwin, Ortley, or, uhh, Esopus Spitzenburg.”

Calla made a face like she’d just licked a moth. “

No. You can’t—you can’t use those as your comps. Those sound like Old People apples. Esopus? We’re not Amish, Dad, god. No, you, like, go to the grocery store and the apples there have fun names, right? Honeycrisp, Pink Ladies, ummm—”

“SweeTango! Oh, Cosmic Crisp, too.”

“Yeah, okay, yeah. Whatever. So, you can’t call it the Paxson. You just can’t.” She made a disappointed face. “Promise me you won’t. It’s mid. It hurts me on the inside. Please promise. Please.”

“Our name matters, Calla,” he said, stiffening. She’d hurt him. But then his face softened and he leaned forward to take a big, sharp bite of the apple. His eyes closed and he breathed through his nose as he chewed. For a moment he seemed lost. He moaned around it. (

Gross.) Finally he said: “You’re right. It’s too good for a boring name. So you’re up, Little Miss Influencer. Influence me. Name this apple.”

Calla scrunched up her nose, plowing little furrows in her brow as she grabbed his wrist and moved it this way and that, pivoting the apple in her view. (She wasn’t going to touch the apple because it was drooling juice from its bite wound.) “Dark, red, pretty. Like I’m staring into something deep—” It almost pulled her gaze to it, even

into it. As if she were staring into the hall-of-mirrors aspect of a gemstone’s facets.

That’s it. “It’s like a ruby. You wanted to name it after us?” At the end of the gravel drive, she saw the old sign that hung there, a wooden sign with their name carved into it. A name signaling their house. Their home.

That’s it, she thought. “There’s no place like home.”

“What?” he asked.

“Ruby Slipper.” She paused. “There’s no place like home. Ruby Slipper. It’s like from that movie. The one with the scarecrow.”

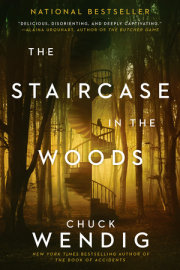

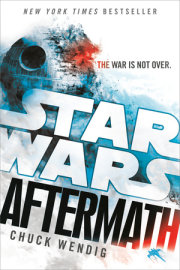

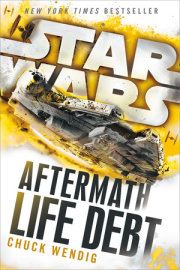

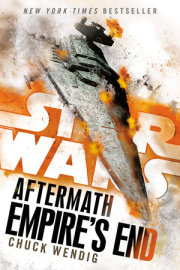

Copyright © 2023 by Chuck Wendig. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.