PreambleI recently discovered that if you walk around New York City while carrying an eighteenth-century musket, you get a lot of questions.

“You gonna shoot some redcoats?”

“Can you please leave?”

“What the hell, man?”

Questions aside, a musket can come in handy. When I arrived at my local coffee shop at the same time as another customer, he told me, “You go first. I’m not arguing with someone holding that thing.”

Why was I carrying around an 11-pound firearm from the 1790s? Well, it’s because I’m deep into my Year of Living Constitutionally. For reasons I’ll explain shortly, I’ve pledged to try to express my constitutional rights using the tools and mindset of when they were written 1787. My plan is to be the original originalist.

I will bear arms, but only those arms available when the Second Amendment was written, hence the musket and its accompanying bayonet.

I will exercise my First Amendment right to free speech—but I’ll do it the old-fashioned way: By writing pamphlets with a quill pen and handing them out on the street.

My right to assemble? I will assemble at coffeehouses and taverns, not over Zoom or Discord.

If I’m to be punished, I will insist my punishment not be cruel and unusual, at least cruel and unusual by eighteenth-century standards (when, unfortunately, Americans considered it acceptable to have your head stuck in a pillory and get pelted by mud and rotten vegetables).

Thanks to the Third Amendment, I may choose to quarter soldiers in my apartment – but I will kick them out onto the street if they misbehave.

My goal is to understand the Constitution by expressing my rights as they were interpreted back in the era of Washington and Jefferson (or, in the case of the later amendments, how they were interpreted when they were written). I want, as much as possible, to get inside the minds of the Founding Fathers. And by doing so, I want to figure out how we should live today. What do we need to update? What should we ignore? Is there wisdom from the eighteenth century that is worth reviving? And how should we view this most influential and perplexing of American texts?

I undertook this quest because reading the news over this past year led me to three important revelations.

The first revelation was just how much our lives are affected by this 4,543-word document inscribed on calfskin during that Philadelphia summer. The Supreme Court’s recent controversial decisions on everything from women’s rights, gun rights, environmental regulations, and religion – all claim to stem from the Constitution.

The second revelation was just how shockingly little I knew about the Constitution. I’d never even read it – not the whole thing, anyway. Thanks to

Schoolhouse Rock!, I was familiar with the “We the People” preamble. And I could recall a handful of other famous passages, most notably the First Amendment, which is beloved by me and my fellow writers (as well as by my kids, who cite it whenever I ask them not to curse at me). But as for the entire document, from start to finish? Never read it.

And third, I realized just how much the Constitution is a national Rorschach test. Everyone, including me, sees what they want. Does the Constitution support laissez-faire gun rights, or does it support strict gun regulation? Does it prohibit school prayer or not? Depends whom you ask.

And it’s not just the issues we’re divided on – it’s the Constitution itself. Is the Constitution a document of liberation, as I’d been taught in high school? Or is it, as some critics argue, a document of oppression? Should we venerate this brilliant roadmap that has arguably guided American prosperity and expanded freedom for 236 years? Or should we be skeptical of this set of rules written by wealthy racists who thought tobacco-smoke enemas were cutting-edge medicine?

It reminds me of a William Blake quote I once read about the Bible:

“[We] both read the Bible day and nightBut thou read’st black where I read white.”And, as with the Bible, whether you see black versus white in the Constitution depends largely on one crucial question:

What is your method for interpreting this text? Should we try to discover the original meaning from when the text was written? Or does the meaning of the text evolve with the times?

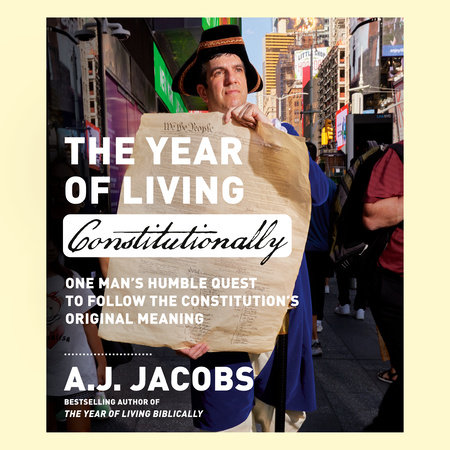

In fact, the Bible-Constitution parallels helped give birth to this book. I decided to steal an idea from myself. Several years ago, I wrote a book called

The Year of Living Biblically, in which I explored the ways we interpret the Bible by following the Good Book as literally as possible. I followed the Ten Commandments, but I also followed the hundreds of more obscure rules. I grew some alarmingly sprawling facial hair (Leviticus says you should not shave the corners of your beard) and tossed out my poly-cotton sweaters (Leviticus says you cannot wear clothes made of two kinds of fabric). I became the ultimate fundamentalist.

The project was absurd at times but also enlightening and inspiring. I found that some aspects of living biblically changed my life for the better (the emphasis on gratitude, for instance). I also learned the dangers of taking the Bible too literally (I don’t recommend stoning an adulterer in Central Park, even if those stones are pebble-sized, as mine were). And I learned how challenging it is to figure out what we should replace literalism with.

I’m not the first to notice that we treat the Constitution and the Bible in similar ways. Scholars have long described the Constitution as the “sacred text” of our “civic religion.” Jefferson called the delegates “demigods.” And as with the Bible, there is an ongoing debate between those who say we need to hew to the original meaning—the camp often called originalists—and those who say the meaning evolves—the camp often called Living Constitutionalists. The two sides have been around for decades, but in the past five years, the originalists have gained surprising power. Five of the six conservative justices on the Supreme Court are originalists of some sort (John Roberts is the exception), a position that has affected their rulings on abortion, gun rights, and many other topics. I felt it was time. I began prepping for a Year of Living Constitutionally.

* * *

Before I started my year, I figured I’d better sit down and actually read the Constitution.

So on a random Thursday night, I set the mood. I lit a beeswax candle, settled into our most spartan wooden chair, and unrolled my U.S. Constitution. It’s a four-page wheat-colored replica I bought on Amazon. Each crinkly page is the size of a poster. I’m accustomed to reading on small glowing screens, so it was an awkward feeling. My wife Julie would be better at this – she still reads the print version of the

New York Times, which I find charmingly archaic (“So what’s President Eisenhower up to today?” I’ll ask. To which she’ll respond, “Oh, because I’m reading it like they did in the 1950s. I get it. Good one.”).

I soldier on and read the first sentence:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form amore perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domesticTranquility, provide for the common defence, promotethe general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty toourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish thisConstitution for the United States of America.Now that’s an inspiring 52 words! I love how it builds tension, comma by comma by comma, till we get to the majestic and self-referential phrase “this Constitution.” I also like the mention of the “general Welfare.” We could all use more attention to “general Welfare” nowadays as a balance to America’s focus on individual rights. I’m also a fan of the mention of “Posterity” – that’s us they’re talking about. We’re the posterity. I’m a part of this American experiment.

I even like the promiscuous use of capital letters. Over the years, several copy editors have told me that I’m an Overcapitalizer. (Ben Franklin wanted to reform American spelling so that all Nouns were capitalized. Sadly, this didn’t happen, but his Advice had an Impact on this Document).

After that gorgeous preamble, I got to Article I. Frankly, it was kind of a letdown. It’s a list of rules for setting up Congress, and the prose switches from grand and soaring to technical and lawyerly.

Copyright © 2024 by A.J. Jacobs. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.