1.

I won't say where I am in this greatish country of ours, as that could be dicey for Val and her XL little boy, Victor Jr., but it's a place like most others, nothing too awful or uncomfortable, with no enduring vistas or distinctive traditions to admire, no funny accents or habits of the locals to wonder at or find repellent. Call it whatever you like, but I'll refer to it as Stagno, for while it's definitely landlocked here, several bodies of murky water dot the area. There's a way that the days here curdle like the gunge that collects on the surface of a simmering broth, gunge you must constantly gunge away.

Still, Stagno serves its purpose. It's so ordinary that no one too special would ever choose to live here, though well populated enough that Val and Victor Jr. and I don't stand out. And we ought to stand out. For it would be natural to ask what a college-age kid was doing shacked up with a thirtysomething mom and her eight-year-old son, and why neither of us worked a job, or why the boy didn't go off to school. Do we ever leave the house? For a brief period, we did, but not much anymore. We stream movies and shows. Val is ordering everything online again, including groceries, the only item she regularly ventures out for being a grease-soaked foot-long hoagie named the Widowmaker that is the carrot for Victor Jr. when he reaches his daily tolerance for our homeschooling. There is no stick. Val handles social studies and arts and I cover math and science, but all in all we get a C+ for conception, execution, and effort, which Victor Jr. is well aware of and is undoubtedly banking on using against his mother someday. He's an exceedingly smart, cute kid, if notably hirsute, something genetically cross-wired for sure because a kid his age shouldn't have arm and leg and back hair and definitely not the downy mustache, the nap of which the boy caresses whenever he's noodling his human child's plight.

In the future Victor Jr. may strategically deploy my name, but we still can't predict the full extent of my presence in his life. What we know is this: Val and I have a good thing going. We try to see our roles as limited in scope and intensity. We aren't aspiring to all-time greatness, whether in homeschooling or partnering. We aren't each other's stand-ins for the world-as-it-should-be. My stated obligations to Val are to treat Victor Jr. better than the sometimes unruly pupster that he is, and to be, as she says, her reliably uberant fuck buddy (ex- and prot-), and finally to pick up around this cramped exurban house so it doesn't get too skanky. In return, I have her excellent company and a place to stash myself for however long we mutually wish. I require nothing of her at all, except that she not ask after my family, or what I was doing before I met her several months ago, or why my only possessions were the very clothes I was wearing, a very small Japanese-made folding knife, and a dark brushed-metal ATM card that until recently magically summoned cash every time I used it.

I know something about Val because she basically told me her recent life story right after we first met in a food court of the Hong Kong International Airport. She was ahead of me in line with Victor Jr., who was as usual gaming on his handheld, and found that her credit cards weren't working and had no cash. When the boy heard this he immediately started wailing about the depth of his hunger, which I have come to know as bottomless. My impulse was to jam a duty-free baton of Toblerone between his oddly super-tiny teeth. But Val, even with her laughing, narrow eyes, the kind certain Asian girls can have, with that wonderful hint of an upward lilt and dark sparkle when they gaze at you that says in a most generous way, Really?, looked like she wanted to don a crown of thorns and climb atop a Viking pyre, so without a beat I paid for their food and was heading off with my own steamer basket of xiaolongbao when she asked if she could meet my parents to say what a gallant young man I was. She actually used the word gallant. When I told her I was solo she hooked my elbow and plunked us down at a table. While her son destroyed his mound of hot and dry Wuhan noodles, Val began telling me she was kind of solo, too, not counting Victor Jr., and then casually mentioned how her husband Victor Sr. was disappeared and probably dead. Maybe because I was freshly adrift myself, smashed to raw bits by circumstances too peculiar to recount, I matched her nonchalance and asked if he was in a kinder place. Something fell away from her wide, sweet face and she proceeded to tell me how some months earlier she had detailed for federal agents every last facet of her husband's dealings with a gang of New Jersey-based Tashkentians that involved Mongolian mineral rights, faux sturgeon eggs, and very real shoulder-mounted rocket launchers, which were supposedly part of an ISIS-offshoot-offshoot's plan to enrich themselves and arm potential client cells in Western Europe. All this was substantial enough to predicate Victor Sr. 's sudden absence from this life and worth a witness protection setup for Val when they got back to the States, a good deal considering she was the legal co-owner of her husband's trading business and faced money laundering and tax evasion charges plus the prospect of having to give up her dear little Victor to foster care.

She said she was certain she could trust me with her story, and that I had an "open and welcoming face," which I must admit that I do. People trust me when they ought not to trust me, which these days is more often than they imagine. She talked about her and Victor Jr. 's visit with a relative in Kowloon, and I gave the much-expurgated tourist version of my own visits to Macau and Shenzhen, and how we were both heading back to the drab life of the US Eastern Seaboard. I told her I was from New Jersey myself, a few counties south of where she and her husband used to live. She asked for my email-I didn't have a phone anymore-and said she would connect with me in a couple weeks, when things got more settled. She didn't ask what I was doing out in this part of the world, which is just like Val. Since then she's asked, received my basic answer, and not mentioned it again. This is one of the many reasons I have quickly grown to cherish her. Val encounters life and persons as they come to her, this total acceptance of the fact that you're here, that you belong to the space you're taking up, that it's all and only yours. A rare thing, IMHO. If you think about it, most persons, including many of those who say they love you, can't help but question your particular coordinates in whatever you're doing or thinking or hoping for, then want to realign you to function more smoothly in their eyes and thereby calm their fretful souls.

Val's soul seems to me a crock of honey set on a warming plate, its flows exchanging imperceptibly from top to bottom so that there's hardly any gradient within, one example being that even when Victor Jr. is at his petulant, grating worst Val will bat her eyelashes twice, very slowly, while expelling the lightest of sighs, and then try to reason with the beast. Normally if her attempts with Victor Jr. fail she flags me, and I automatically fix us a snack. A couple Shin Blacks for us ravenous boys, grilled salami-and-cheeses. I watch him eat in his dainty Victor Jr. way, his thumbs and index fingers pincering the food, the other digits splayed out, and then wink if he's especially pleased. His micro-teeth furiously snip and grind and pulverize. Even if he was my own issue I couldn't deny that he might very well end up a charming and effective sociopath, one immensely successful, snarfing my offerings with warbles in his throat while picturing his foes and beloved alike in hot fat, deep-frying like chicken wings.

But at some point we're all extra hungry, aren't we, if not necessarily for grub? And if not it's probably because we've too much of a fill. Take me. I'm on the other side of feeling I was about to burst, having skipped out on this last semester to hit as many tables and stations and taps of life's grand buffet as I could, which I had no idea could be so available, so glorious and miserable, so heroic and lamentable at once. Sometimes Val senses me going funny and intuitively gives me space to sit by myself on our splintery back deck with a blunt, or to veg out when we're eating whatever we've ordered in. Sometimes Victor Jr. will bark at me, Yo, Tilly! Wake up! Val would likely have no trouble believing the things I've done and seen in this past year and maybe only wonder how I ever returned after being in so deep. I would say to Val that I don't know. I don't know how it was that I came back, because I didn't want to come back, ever, until I did.

Though now that I am back, I'm grateful to be with her and nobody else. Would I die for her? That's a weird question to bring up but I know I would. It doesn't mean I love her or value her most. I do love her and that's that but sometimes I think I love the world more. I'd die for the world, if this makes any sense, just because Val is one of the many remarkable phenomena in it. And this means I'd die for Victor Jr., too. Am I totally messed up? If you're willing to die for too many things, does it mean you care way too much or too little? Does it mean you'll break down very soon?

Maybe. I'm cleaning up the dinner dishes while Val gives Victor Jr. his bath (which he still insists on her doing and probably will until he's in college) and once we both have a go wrestling the little porker into his pajamas, Val and I will climb into the frilly canopied bed that came with this rented place and fire up the flat screen and watch until our pupils start vibrating, when we'll fall asleep or else get busy. We leave the screen on so I get to see Val in my favorite way, her nakedness strobed dusky blue, the cold flame of her body flashing on and off above me. She's always ready, if you know what I mean, which she tells me is not always the case for women at her older young age. Sure, she's got a lot of years on me and probably before this last year I might have gagged on noticing any dustings of gray in the hair of a woman I was getting with, but then I would have caused Val to swallow back the bile, too, for how painfully unfledged I was. My twee neat goolies. If they're no fatter now at least they've got an educated hang, like the bags under old soldiers' eyes, each drape an unsung but unforgettable campaign. Val got this about me, right there in the airport food court, she somehow understood I'd been away on a harrowing journey and that I should receive some sheltering for a while. Sometimes the plush tide of her hair on my belly, my chest, my face feels so good tears come to my eyes and she'll rub her eyes with the wetness. Our lashes interlace. Our noses rumba and slide. And we taste the salt from ourselves, which is the tastiest salt there is.

Recently, I did a good thing for Val. IÕm still thinking about it. I havenÕt told her about it yet and hope I never have to, unless sheÕs really got to know. I was actually out shopping for some mini-barbells for Victor Jr. and when I was driving back into ValÕs neighborhood I noticed a shiny black SUV cruising very slowly down at the far end of a street parallel to ours. I pulled over and pretended to make a call. The SUV was creeping forward like a limo might, but something about the way it was moving was sketchy, it wasnÕt really pausing long enough to be checking house numbers, more like pretending to check but being lazy about it, as if the numbers didnÕt matter. An older lady was walking her dog and the SUV stopped beside her and she warily went over to it, her Pekingese yapping. The person in the SUV must have said something funny or charming because the lady smiled and tucked her dyed reddish hair behind her ear. Then she craned in slightly, clearly examining something the driver was showing her; then she shook her head. I made a quick U-turn and from the opposite direction sped to our place. I slipped the car inside the garage and without pausing grabbed a baseball cap from the rack and doffed it bill-back and borrowed the neighbor kidÕs BMX lying in the grass and pedaled out as fast as I could so I wouldnÕt be seen leaving our house. When I saw the black SUV turn onto our street I hooked in earbuds and ran over evening papers on the driveways, tightroped the curb, tried to bunny hop an ornamental yard stone, and fell on my ass but popped right up again like any kid would. The SUV-I could make out the driver now, white guy, dark sunglasses, short cropped dark hair-accelerated ever so slightly and drifted over to the wrong side of the street to where I was doing a wheelie on the sidewalk.

The smoked window rolled down. The driver was muscly in the neck and shoulders and arms but must have been a shrimp otherwise because his seat was pitched high and forward, very close to the steering wheel, just the way my tiny grandma used to have hers while she drove, her knuckles practically grazing her chin. This guy was maybe late thirties at most but had a receding hairline and was rocking an overmanicured five-o'clock shadow plus oversized mirror-shade aviators and stippled black leather driving gloves and I almost asked him how long he'd been driving Formula 1, but instead recast myself as goat-faced and sleepy-eyed, as dim as the fescue I imagined myself chewing, and just stared at the dude like he was an endless plains vista, a portrait of beige.

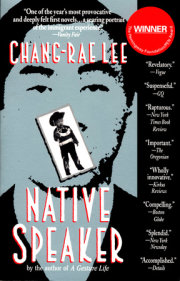

Copyright © 2021 by Chang-rae Lee. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.