March 1

We are sooo not supposed to be here.

I know it the second the door to P.J.’s dings when we open it, but I can’t just leave my best friend, Sneaky, hanging, so I walk in behind him, my stomach karate-chopping the whole time.

Sneaky acts like he’s been here before, which he probably has. I’ve only heard horror stories. P.J.’s Liquor Spot is a little store on the corner of 5th and Creighton, and if you know anything about Creighton, you know that something bad’s always happening there. Like, every week. Sneaky’s mom and mine always tell us to stay away, even though P.J.’s has the cheapest candy and ice cream bars. For the most part, I listen. Sneaky doesn’t.

“Yo, hurry up,” I say to Sneaky in a whisper, noticing some older kids watching us with narrowed eyes.

As if being on Creighton isn’t bad enough, P.J.’s is also kinda dark inside, and not that clean. The music playing makes me feel mad for no reason, and a frown inches across my face.

I follow Sneaky to the candy aisle, which is right near the front counter. While I keep glancing around, Sneaky studies the candy bars, taking his time when we need to get outta here!

“Aight, ’Saiah, get six Snickers and six Milky Ways,” Sneaky says, reaching for Skittles and Starburst.

I grab what he says, and some bubble gum, too.

“Mike O wanted gum yesterday, remember?” I say.

“Oh yeah! Good look, bro.” Sneaky grabs some packs of M&M’s, and I get Butterfingers and Laffy Taffy. By now, our arms are pretty full.

“Some 3 Musketeers?” I ask, but I don’t get an answer.

Bam! Bam!

I almost drop all the candy on the ground when the guy at the register bangs on the counter to get our attention.

“Hey, candy man,” he calls, nodding at our stash. “Y’all got money for all that?”

“Yeah,” says Sneaky, walking to the counter. The guy studies us to make sure we don’t try to slip anything into our pockets or backpacks. We dump everything on the counter and the guy starts ringing it up.

“Eight thirty-five,” he says, putting the candy into a bag but not handing it over until Sneaky gives him the money. Eight dollars and thirty-five cents exactly. Sneaky don’t play when it comes to his candy business and his money.

The guy slides the bag toward Sneaky, and he puts it into his backpack before we walk out.

“That place is crazy!” I say, breathing a sigh of relief, but Sneaky doesn’t notice.

“Yo, I’ll make, like, a fifteen-dollar profit once I sell this,” he says, all excited. “See, that’s why I come here.”

Sneaky’s definitely right about the candy prices in P.J.’s. But when I hear the door ding again and glance over my shoulder, I wish we had just gotten our candy at the 7-Eleven near Sneaky’s house.

I stop walking, and so does Sneaky, trying to figure out what I’m staring at.

“What?” he asks.

“Nothing,” I say. I have to force myself to turn around and keep walking, instead of racing back to P.J.’s. “Thought some of those dudes were coming for us.”

Sneaky sucks his teeth. “Man, forget them. They’re not gonna do nothing to us.”

I don’t remind him that a kid got jumped over here just last week, or that Creighton schools are our rivals. I’m too busy thinking about other things.

Like how I just saw Mama go into P.J.’s, and how I know exactly what she’ll come out with.

March 2

Mama says I always liked words; that I was talking before I could walk, and reading and writing before I even got to kindergarten. For some reason, I like poems. Nobody knows that except Mama and Daddy, and maybe Charlie, my little sister. Sneaky knows a lot about me, but he don’t know that.

According to Mama, I get my love of words from my daddy, who wrote tons of stories in his notebooks. I like making words fit together like puzzle pieces, and coming up with the perfect rhyme. But since Daddy died four months ago, nothing fits and nothing rhymes, no matter how hard I try to make it.

Mama didn’t do very well after Daddy died, and neither did me and Charlie, I guess. But at least me and Charlie started to have some sunny days after a while. Mama’s been all rain. She started missing days at work, and then she stopped going at all. The less she went to work, the more bottles started showing up around our apartment, like long-lost cousins who never leave, all of ’em with the labels torn off. Mama probably thinks I don’t know what she’s drinking, but I do. And I know it’s only making things worse--so bad, we couldn’t live in our apartment anymore.

Today is Day 17 in the Smoky Inn, which is what I call the motel we’ve been staying in. It’s really called the Sleep Inn Motel, but everything smells like smoke, so they should really change the name. Most of the time, Mama lays in bed all day, which means I have to look out for Charlie, who’s four and pretty annoying. Like right now, she just drew a pink flower in my notebook, the one I used to write all my poems in.

“Look, ’Saiah!” Charlie says, like I’m supposed to be excited that she drew over my poem about rain.

Rain is just like tears from the sky.

Cuz even things up high have to cry.

“Charlie, why’d you do that?” I say, snatching the notebook from her.

“Cuz,” she says, shrugging and bouncing off to the bed she shares with Mama. Mama doesn’t even stir when Charlie jumps on the bed, and she doesn’t say anything when I tell Charlie to leave my stuff alone.

“But you don’t write in it, ’Saiah,” Charlie says, sucking on two fingers, her most disgusting habit.

Charlie’s right, though. I haven’t written one word this year. Every time I try to, it’s like the words freeze in my brain, which makes the lead freeze in my pencil. Nothing comes out.

I flip through the pages in my notebook, and half of them are blank. Wonder why Charlie didn’t at least draw on an empty page.

Clouds are the Kleenex to wipe the sky's face.

They move away quick when the sun gets in place.

Other than the scribbles all over it now, it’s a pretty good poem. There’s a pen on the raggedy motel table; I reach for it and turn to a blank page.

“You gonna write something about me, ’Saiah?” Charlie calls.

“No,” I say.

I stare at the page, but no words come out. Ten minutes later, when I need to leave for school and Charlie starts whining that she’s hungry, my page looks exactly the same.

Empty.

March 4

Sneaky’s snoring is like thunder trapped in a blender. No matter how tight I squeeze the pillow around my head, it’s still loud.

I heard you should nudge a snoring person, and that’ll make them stop. I kick Sneaky, like, three times, and it doesn’t work!

The room is dark, but it’s that half dark/half light that means it’s about 7:06, way too early to be awake after staying up till 3 a.m.

Sneak turns over, farts, and keeps snoring, and that’s when I know I won’t be getting any more zzz’s. I pull the pillow off my head and sit up. Sneaky’s room is small, and he shares it with his big brother, Antwan, who’s pretty much a jerk. But it beats being stuck in that smoky motel room. If it was up to me, I’d probably live with Sneaky, instead of just spending the weekend with him, which I had to beg Mama to do.

I reach for my backpack and pull out my daddy’s gold notebook, which I’ve been reading, like, every day since I found it when we still lived in our apartment. I keep his notebook next to mine in my backpack. Guess I’m thinking his words might jump over to my notebook if I keep them close to each other. Unlike me, Daddy filled his notebook from beginning to end with his thoughts about things, but mostly with stories called “The Beans and Rice Chronicles of Isaiah Dunn.” In the stories, a ten-year-old kid superhero named Isaiah Dunn goes on tons of secret missions and gets his power from bowls of beans and rice. When I first found Daddy’s notebook, I thought it was cool that he wrote about me as a superhero. I wish all the beans and rice Mama’s been making would give me some type of superpower in real life.

I count sixty-four pages left to read in Daddy’s notebook, which seems like a lot, but if I keep reading every day, I’ll be done in no time. That makes me read extra slow. I don’t wanna think about what will happen when I get to the end. Daddy should’ve written “Isaiah Dunn and the Never-Ending Tale,” where the notebook has magic powers to keep the story going forever. In the story I’m reading now, Isaiah Dunn races against the clock to find a clue hidden in a box of cereal at the grocery store.

The grocery store part makes me think about Mama, and I stop reading. I wonder what she’s doing right now, and if Charlie is with her. I think Charlie hates being in the motel as much as I do, and I feel a little guilty for leaving her alone for the weekend. I’m thinking maybe if we get enough money, we can find a real nice place to live, and then Mama would feel better. I know I would.

I flip to the page in Daddy’s notebook where he wrote about fears. He wrote that when you name a fear, it becomes defeatable, and he put down some of his fears. Some of them are funny, like “octopuses” and “fire hydrants” and “wasps.” Others are scary, like “wolves” and “burglars” and “our car going off a bridge into deep water.” I’m scared of daddy long-leg spiders, tsunamis, and sometimes dogs. I write those down next to Daddy’s list. Then I add: eating beans and rice every day, not being able to write poems, and having to live at Smoky Inn forever. My last fear is the worst one. Losing Mama, too.

I reach down to the bottom of my backpack for my stash of money, which I keep in one of Daddy’s old socks. I empty the sock out and count all the change and dollar bills: $19.78. Nowhere near enough to get us a sweet apartment.

I keep reading, hoping that maybe I’ll find a money-making idea from the story, but my eyes get super heavy, and the next thing I know, Sneaky’s nudging me.

“Yo, wake up, Mr. Librarian!” He smirks.

The room’s completely light now, and my neck is sore from how I fell asleep.

“Okay, Sir Snores,” I say back. I put Daddy’s notebook in my backpack before Sneaky can clown me for what I’m reading. He’d definitely clown me for my book of poems.

“Whatever,” Sneaky says. “I don’t snore.”

I shake my head. No use arguing with him. If I had a phone, I’d just record him or something.

“You hungry?” Sneaky asks, reaching for his PlayStation controller. He’d play for hours without even thinking about breakfast, but not me.

“Yeah,” I say, and my stomach rumbles automatically. Sneaky’s mom actually makes real breakfast, like, every day, and I’m catching a whiff of goodness right now! I beat Sneaky to the kitchen, and when I get there, I see a stack of pancakes on the table--golden brown, not burnt and lumpy like the ones Mama makes at Smoky Inn. Right next to the pancakes is a plate of perfectly crispy bacon, and Sneaky’s mom is scrambling eggs at the stove. Everything smells so good, my stomach rumbles again.

Sneaky’s mom takes one look at us and makes a face.

“Uh-uh,” she says. “Y’all can take your stank-breath, crusty faces to the bathroom before you sit at my table.”

“Ma, c’mon!” whines Sneaky, walking closer to her.

“Sneaky, don’t play with me!” she says, holding a hand in front of her nose, like he smells so bad it might mess up her face. “And, Isaiah, you not a guest; you know the drill.”

I don’t stick around complaining, just go to the bathroom and get my toothbrush from where I always keep it, in the second drawer on the right. I brush, use mouthwash, and wash my face with a cloth that smells just like the Laundromat on Michigan Avenue.

“That’s better,” Sneaky’s mom says when I come back to the kitchen. “Go ’head and fix a plate.”

By the time Sneaky wanders back in, I already have butter and syrup on the pancakes.

“So what are you guys doing today?” asks Sneaky’s mom, like she always does at breakfast. Me and Sneaky lock eyes, and we both talk at the same time.

“We gotta clean up the room,” Sneaky says.

“And maybe go to the park,” I add.

“Plus, ’Saiah’s gonna test me on my spelling words,” Sneaky says.

See, we learned real quick that if we don’t have a plan, and just shrug and say “I dunno” when Sneaky’s mom asks what we’re doing, then she’ll have us sweeping, scrubbing walls, wiping down the windows, and other weird chores.

“Um-hmm.” Sneaky’s mom gives us a look like she kinda believes us, kinda doesn’t. “Well, y’all can pick up a few things for me from the store when you go out, okay, Sneaky?”

“Uh-huh.” Sneaky’s mouth is full of pancake, so I add, “We can do that, no problem.”

“Thank you, Isaiah.” Sneaky’s mom pats my arm. “Somebody knows the right way to answer a question around here.”

She stands, thumps Sneaky on the head, and walks out of the kitchen with her food.

“Make sure y’all wash your plates!” she calls.

“Dude, we gotta bounce before she makes us do laundry or something,” Sneaky says, taking his plate to the sink. I grab another pancake and pour syrup over it. No way am I passing up seconds.

Once we’re done washing our plates, we head to Sneaky’s room to clean up, but we end up playing Madden NFL on his PlayStation instead.

“Taste the turf!” Sneaky yells when he sacks my quarterback, and it wakes Antwan up.

“Yo, shut up!” Antwan growls, throwing a pillow that hits both of us in the face. Sneaky throws the pillow back, and turns the volume down on the TV.

But when Sneaky’s running back fumbles a few minutes later, and I scoop the ball up and run for a touchdown, I forget all about Antwan and jump up screaming. Problem is, Antwan jumps up, too, and his eyes are a scary red.

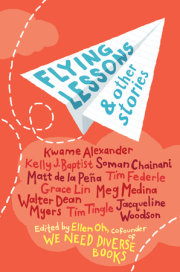

Copyright © 2020 by Kelly J. Baptist. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.