chapter i

THE MOTIONS OF CELESTIAL OBJECTS

The universe is not is; it appears. The sun and stars appear to rise in the east and set in the west. The moon appears to change shape every twenty-eight and a half days, growing into a circle and then disappearing into nothingness, setting the calendar element we call a "month." The constellations and solar system appear to rotate around the Earth, tracing lines of stardust across the night sky.

But this isn't the truth. Or, rather, the full truth. There is a reality-an objective, scientific, physical process-for how things move, evolve, and decay. There is an explanation for the motion of celestial bodies, a description anchored in physics. Our perspective is limited in scope: we see the universe as it appears. We grab a small corner of the picture at its ends, hands brushing along the creases as we pull, pull, pull, dragging it across the frame until that small corner brushes up against all four corners, obscuring the hidden reality behind its borders. We lay claim to it and call it Truth. We say, "This is what the universe looks like."

We're wrong.

The sun and stars only appear to rise in the east and set in the west; they do not actually traverse our skies and plow through the atmosphere each day until they rest on the opposite end of the Earth. If this were true, the Earth would be at the center of the universe. We would gaze out and see celestial bodies orbiting around, stars flaring, and planets cascading through space as we sit like kings at the universe's center, crowns alit with stars as we command our celestial empire. This is an easy picture to believe, an ego-centered approach that's survived for thousands of years, mirroring our lived experiences. We are the protagonists of our own stories, the heroines in our fairy tales.

But it's not the truth.

The Earth is not the center of the universe. It is a small, fragile world floating upon the waves of spacetime amongst a sea of worlds. It orbits an average-size star alongside seven other planets, making up the local cosmic neighborhood we call the solar system. What makes the Earth remarkable is not its position in the universe-many Earth-sized planets orbit their stars close enough for liquid water to exist, but what inhabits it. It is not just the Earth's liquid blue oceans but its vast desert plains too; the oxygen-rich atmosphere and solid molten core; the millions of species and the complex, diverse ecological systems-all of which combine in an exquisite, unique dance to make the Earth special.

It is the stuff that makes Earth ripe for life.

The Earth is the third planet from the sun. But because the Earth spins, rotating around its slightly tilted axis, the sun appears to rise and fall, ushering in day and night. Every twenty-four hours the Earth rotates around its axis, plunging half of the planet, the side facing away from the sun, into darkness and the other half of the planet, the side facing toward the sun, into sunlight.

This is the complete picture, the invisible explanation that we cannot actually feel because we are stuck to the Earth by gravity. As the Earth flies through space, so do we.

Over the course of a night, the other planets in our solar system follow the same line as the sun across our skies, rising in the east and setting in the west. But over the course of a year, they appear to carve out their own paths, wandering across spacetime seemingly of their own accord and drifting against the crowd of stars from west to east. Contrary to our intuition, this is not because these planets are traveling on different trajectories through space but because they are orbiting the sun more slowly than the Earth is. The apparent difference in speeds between the Earth's orbit and the orbits of these planets creates the illusion of "retrograde" motion, as they appear to travel backward across our sky.

The Earth drags the moon in tow as it completes its orbit around the sun. To us, the moon appears to change shape, growing into a perfect circle and then fading into nothing over a twenty-eight-day cycle. But the moon does not swell and shrink. In fact, the moon itself orbits around the Earth just as the Earth orbits around the sun. When the moon is on the opposite side of the Earth with respect to the sun, the sun's rays perfectly hit the lunar surface, illuminating the side facing us and making it a full moon. On the other hand, when the moon is on the side of the Earth nearest the sun, the sun's rays are blocked, obscuring the moon and plunging it into darkness. In this configuration, we see a "new moon," which looks like a moon just out of light's reach. But in reality, we're just not seeing the other side of the moon, the one hit by the sun's rays.

This is contrary to what we might think as we rest our feet atop blades of grass and gaze up at the sky. We convince ourselves that what we see must be true. Our eyes take in the motions of the stars and the apparent reality of the planets painted across the canvas of the night sky and we think, This is it.

But our eyes can't possibly reveal the truth: that we're on a rock hurtling through space at thirty kilometers per second. And that our cosmic neighborhood, our solar system, is in fact orbiting the center of our galaxy, a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A* (the asterisk conveying the excitement of discovery, since atomic physics designates excited atomic states with an asterisk). And this galaxy, our home, is just one of billions. At some point, numbers cease to mean anything as our brains grapple with the incomprehensible scale of the universe.

It's difficult to fathom what we can't see or touch, taste, or smell. But we force ourselves to continuously push beyond what we see right in front of us for a chance to glimpse the unknown. We pen poems and solve math problems, paint in watercolor and write code, read books upon books and peer through telescopes to learn more about our home, the universe.

These pictures are still incomplete. We view the world and our place within it through the lens of our lived experiences, our own struggles and dreams. But it is in this messy place of complexity that we have a chance of learning something fundamental and true.

We just have to be brave enough to question our perceptions. Somewhere underneath our biases and limited perspective is the entire universe, waiting to be discovered.

We just might not understand it yet.

I’ve spent a lot of my life in cars. During the school year, from kindergarten through senior year of high school, I drove forty-five minutes to and from school each day. The drive could be as long as an hour and a half if there was bad traffic clogging up Highway 360. When you add in the trek to tennis practice (on one end of Austin) and tutoring (on the other end), I probably spent three total hours every day in the seat of a car.

I didn't hate the drives, partially because I could catch up on missed sleep and partially because of StarDate.

Every day, at exactly 6:57 a.m. and 4:57 p.m., Sandy Wood's voice would float through the speakers in our silver Volkswagen while she hosted a brief two-minute astronomy show. In order to listen, I had negotiated a hard-fought deal with my parents: I agreed to listen to their choice of classical music and five-o'clock news if they let me listen to StarDate. It took less convincing than I expected-my mom hid an odd smile of pride when I proposed the deal-but I refused to think too hard about it, and with a quick thank you was able to spend four minutes per day learning about the stars.

In first grade, mornings begin at 6 a.m. By 6:15, I've packed my backpack and furiously checked that I had all my homework before my mom and I slide into the old family Volkswagen. By the time we leave the driveway, the sun is still below the horizon and darkness cloaks the Texas landscape. I sit rigidly in the back-seat, eyes scanning across lines of homework problems to double-check my work, while we drive from the outer suburbs to the other side of Austin, where my school, St. Andrew's, is. The houses grow bigger and bigger over the course of the drive, rising with the sun as we pass the gated neighborhoods of Westlake and estates of Tarrytown.

My mom's scent washes over me as we drive, lemongrass and pumice stone laced with cigarette smoke. She refuses to smoke in the car or the house, claiming she wants to shield me, but it has long ago seeped into her clothes and the crevices of her skin. I scrunch my nose when a wave washes over me.

Ethereal music soars through the speakers, signaling the beginning of a new episode of StarDate. "Mom, can you turn it up?" She turns the dial and Sandy's voice grows louder. I relax into my seat and count the trees whipping by as we round the corner onto Bee Cave Road. They look like broccoli, the dark-green leaves of cedar displayed like chunks of great big florets.

"Today on StarDate: Venus, Earth's sister, is visible just above the moon at twilight. It will look like a bright star, but unlike other stars strewn across the night sky, it won't flicker." I let her voice, imbued with the magic of Venus and the cosmos, lull me into a semi-meditative state as we get closer to school. The sky brightens over the course of the drive, transitioning from black to orange to yellow, and when it finally hits pale notes of blue, we are pulling into the long driveway marking the entrance to St. Andrew's.

St. Andrew's is what you get when you combine white liberal Austin with the Episcopalian church. The elementary school is auspicious; a large cream-white slab of marble marks the entrance, "Crusaders" engraved in bold. It was unclear what St. Andrew's meant by calling ten-year-olds crusaders. And what were they crusading for: the crucifixion of their enemies? Nonbelievers?

Beside the slab is a flagpole, flying a triumvirate of flags: the United States, Texas, and the St. Andrew's flag. The Texas flag is larger than the other two, but just barely: our school flag makes up for its size with fat white stark lines slashed across a pale-blue background, domineering in its frankness. The American flag, on the other hand, is almost perfunctory, flying amongst the others yet never fully visible.

“Can we look at Venus tonight? Did you hear Ms. Wood say it’ll be visible before sunset?” I ask my mom plaintively as we pull up behind a forest-green Mercedes. She smiles a bit, the sun emerging from clouds as she tucks a stray strand of chemically straightened brown hair behind her ear. No matter how many times she has tried straightening it, going to expensive salons and spraying bottles called “sleek” and “soft,” her hair stays frizzy, the Egyptian coils refusing to fully succumb to the beauty ideals of the West. When I see her touch her hair, I subconsciously reach for mine, reassuring myself that my curls are temporarily tamed before entering the building.

"Maybe, but you have tennis at five and we need to go through your spelling homework to review for your test on Friday."

"But that's in three days!" I protest. "I have time!"

"We don't want to disappoint your dad, do we?" Indignant, but realizing the futility of fighting back, I suck in a quick breath. She twists to look at me, the weight of expectation sharpening her gaze.

"No," I mutter, "we don't." I grab my backpack and leave the car without saying goodbye.

I stick my backpack into one of the light-blue cubbies lining the hallway, painted to match the school colors, and take a seat at my desk. My name is written on a sheet of paper folded up like a tent at the edge of the table, written in orange and yellow highlighter. On the other side of the sheet, the one facing me that people couldn’t see, I’d inscribed my name in Arabic: three seemingly distinct groups of lines and curves, four dots and a long elif. I love writing my name in Arabic, love feeling the beauty of the curvature of the letters as I scratch them onto the page. The Arabic alphabet isn’t quite as beautiful as the alphabet of hieroglyphics we have hanging in our living room at home, but it’s far prettier than the English one, made up of coarse lines and brutish scratches. I straighten the name-tent, bending it slightly to hide the Arabic from full view.

My mom taught me how to write my name in Arabic using my toy chalkboard. When she took the pink chalk-I wanted blue-and guided my hand through the shapes, she said that when she was a child growing up in Egypt, her mom taught her how to write too. That was before bombs fell from the sky, before her grandparents constructed a shield of sandbags to protect them from the air raids.

Before she left Egypt.

My grandfather Mohamed was a director of demography for the United Nations. His job took my grandmother, my mom, and her three brothers all over the world. First was India-my mom's favorite, she says, the place that felt closest to home. Then was Switzerland, which was beautiful and cold and where she learned to hate her Egyptian curls. Finally, they relocated to the headquarters of the United Nations: New York.

My mom loves New York. She pronounces it with the slightest hint of a British accent: New Yohk. I think she resents moving to Texas for graduate school. New York has culture, community, life. She doesn't stand out in New York. No PhD will ever be worth leaving that behind, even if graduate school brought my parents together. Even if she now gets to share the title of Dr. El-Badry with her father.

Texas, she says, will never be her home.

I wonder if it will ever be mine.

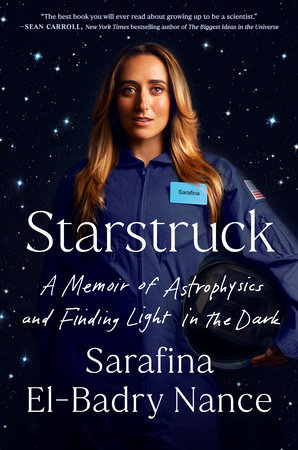

Copyright © 2023 by Sarafina El-Badry Nance. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.