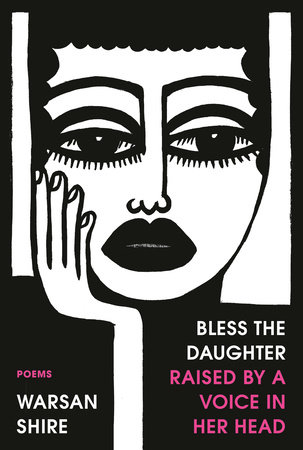

Extreme GirlhoodA loop, a girl born

to each family,

prelude to suffering.

Bless the baby girl,

caul of dissatisfaction,

patron saint of not

good enough.

Are you there, God?

It’s me, Warsan.

Maladaptive daydreaming,

obsessive, dissociative.

Born to a lullaby

lamenting melanin,

newborn ears checked

for the first signs of color.

At first I was afraid, I was petrified.The child reads surahs each night

to veil her from il

protecting body and home

from intruders.

She wakes with a fright,

someone cutting the rope,

something creeping

deep inside her.

Are you there, God?

It’s me, the ugly one.

Bless the Type 4 child,

scalp massaged with the milk

of cruelty, cranium cursed,

crushed between adult knees,

drenched in pink lotion.

Everything you did to me,

I remember.

Mama, I made it

out of your home

alive, raised by

the voices

in my head.

HomeINo one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark. You only run for the border when you see the whole city running as well. The boy you went to school with, who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory is holding a gun bigger than his body. You only leave home when home won’t let you stay.

No one would leave home unless home chased you. It’s not something you ever thought about doing, so when you did, you carried the anthem under your breath, waiting until the airport toilet to tear up the passport and swallow, each mournful mouthful making it clear you would not be going back.

No one puts their children in a boat, unless the water is safer than the land. No one would choose days and nights in the stomach of a truck, unless the miles traveled meant something more than journey.

No one would choose to crawl under fences, beaten until your shadow leaves, raped, forced off the boat because you are darker, drowned, sold, starved, shot at the border like a sick animal, pitied. No one would choose to make a refugee camp home for a year or two or ten, stripped and searched, finding prison everywhere. And if you were to survive, greeted on the other side—

Go home Blacks, dirty refugees, sucking our country dry of milk, dark with their hands out, smell strange, savage, look what they’ve done to their own countries, what will they do to ours?The insults are easier to swallow than finding your child’s body in the rubble.

I want to go home, but home is the mouth of a shark. Home is the barrel of a gun. No one would leave home unless home chased you to the shore. No one would leave home until home is a voice in your ear saying—

leave, run, now. I don’t know what I’ve become.III don’t know where I’m going. Where I came from is disappearing. I am unwelcome. My beauty is not beauty here. My body is burning with the shame of not belonging, my body is longing. I am the sin of memory and the absence of memory. I watch the news and my mouth becomes a sink full of blood. The lines, forms, people at the desks, calling cards, immigration officers, the looks on the street, the cold settling deep into my bones, the English classes at night, the distance I am from home. Alhamdulillah, all of this is better than the scent of a woman completely on fire, a truckload of men who look like my father—pulling out my teeth and nails. All these men between my legs, a gun, a promise, a lie, his name, his flag, his language, his manhood in my mouth.

Bless This HouseMother says there are locked rooms inside all women.

Sometimes, the men—they come with keys,

and sometimes, the men—they come with hammers.

Nin soo joog laga waayo, soo jiifso aa laga helaa, A man who won’t listen to words, will listen to action.

I said

Stop, I said

No and he heard nothing.

Perhaps she has a plan, perhaps she takes him back to hers.

Perhaps he wakes up hours later in a bathtub full of ice,

dry mouth, flinching at his new, neat incision.

I point to my body and say

Oh, this old thing? No, I just slipped it on. Are you going to eat that? I say to my mother, pointing

to my father on the dining room table, mouth stuffed with a red apple.

The bigger my body is, the more locked rooms I find. The more men

queue at the door. Ahmed didn’t push it all the way in, I still think about what he could have opened up inside of me. Ali hesitated at the door for three years. Johnny with the blue eyes came with a bag of tools he’d used on other women: one hairpin, a bottle of bleach,

a switchblade and a jar of Vaseline. Yusuf called out God’s name

through the keyhole and no one answered.

Some begged, some climbed up the side of my body like moss

looking for a way in. Some said they were on their way and never came.

Show us on the doll where you were touched, they said.

I said

I didn’t look like a doll, I looked more like a house. They said

Show us on the house. Like this: two fingers down the drain.

Like this: a fist through the drywall.

My first found a trapdoor in my armpit, he fell in, hasn’t been seen since.

Once in a while I feel a quickening, something small crawling up.

I might let him out. Maybe he’s met the others—males

missing from cities or small towns and pleasant mothers,

who tricked and forced their way in.

Knock knock.

Who’s there?

No one.

At parties I point to my body and say

Oh, this old thing? This is where men come to die.

Copyright © 2022 by Warsan Shire. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.