chapter 1

Okay, I know that the sunset is majestic and timeless and awe-inspiring and everything, but also there was some ice cream dripping onto my hand and it was extremely important that I tend to that at once.

And yes, the light did spread out over the water like sparkly popcorn, and yes, itwas cool the way the sun hovered trembling above the horizon. However, I also had a big scoop of Nutella ice cream, which is my absolute favorite, in a waffle cone, which is also my absolute favorite, and my ice cream was melting fast in the hottest August on record. The sun would set again tomorrow but my hand might be sticky and gross for the whole ride home because my dad, unlike my mom, doesn’t carry a purse filled with wet wipes.

“Told you to get it in a cup,” Dad said. He was taking leisurely bites of his mint chocolate chip, gazing out at the Pacific. Little bites, like he had all the time in the world, which I guess he did because even if his ice cream melted into soup (which is great, I love ice cream soup in an appropriate container), he wouldn’t have the whole sticky-hands problem that I was currently struggling to prevent. Not to mention that I was wearing one of my cutest dresses, cream-colored with a halter top and a swishy skirt, and I did not want it to have a sticky brown splotch forever. Even if I was about to outgrow it.

I grumbled at him, working my tongue into that space between my ring finger and pinky.

“What’d you say?” he asked.

“I said, grumble grumble grumble!”

“A compelling point,” said Dad, and turned his attention back to the sunset. I turned back too, and noticed that the railing came up to his belly, and it hit me right above mine. I was almost as tall as my dad now. When did that happen?

Dad came up with this tradition when I was seven. He would pick a last day of summer, when it would stay warm and bright for hours and hours. Drive the two of us down to “the city,” also known as Seattle, but my parents always called it “the city” like they were describing a bodily function that’s perfectly natural but also embarrassing to do in public. We’d get dinner at a restaurant that doesn’t exist in our town, usually something I’ve never had before (this time it was fancy ramen, which would be my first choice for a cold winter night but maybe not my first choice for a hot summer day). Then we’d wander around the little tourist shops, find some cool street performers and give them dollars, and end by watching the sun set over the Sound.

Dad always called this “father-daughter bonding,” but I wished he wouldn’t. Calling it “bonding” made me worry that I was doing something wrong, like instead of scouring novelty stores for those smashed-penny machines we should be having intense heart-to-hearts about how fast I’m growing up and how glad he was that I’m his daughter. I wished he’d say “Hey Bananabelle”—(yes, that’s what he calls me sometimes—) “have you ever had tandoori? You should try it, it’s delicious” or “There’s a new exhibit on raptors at the natural history museum! I love raptors, want to go with me?” That way we could do the same fun stuff, eat dinner, have a good time, and not feel like we were doing something meaningful to cement our father-daughter relationship. He’s my dad, I’m his kid, I didn’t get why he wanted to make it into such a thing.

Anyway, so we were watching the sunset, or at least he was watching the sunset and I was sneaking peeks of it while avoiding an ice cream catastrophe. He was probably thinking deep thoughts about the universe and how fast I was growing up and how the sun is eventually going to explode, which will kill us all, if climate change doesn’t get us first. I was thinking about all those things and also how I should have gotten a cupand a cone. That would have been genius.

I glanced up at the sun again. Ouch. “Shouldn’t we be wearing sunglasses or something?” I asked. “Don’t you care about my eyes?”

“You’ll be fine,” Dad grunted. “Strengthens your retinas.”

I was almost sure he was joking about that. I knew you weren’t supposed to look directly into the sun, but also I couldn’t tell what kind of mood he was in. Sometimes he liked to joke around, would tease me and I would tease him back and it was great. Sometimes he got prickly, and grimaced every time I tried to say something funny. He had started out the day in a good mood but had gotten quieter and quieter, and I knew better than to try to bring him back. It was almost time to go home anyway. Phew.

Finally I looked up from my Nutella-stained hands, just in time to catch the sun slipping below the water like magic, and I really did get why the sunset was such a miraculous thing. Even though it happened every day. We turned away from the railing without speaking and started the long trek towards the car.

As we walked, I tried to soak up the last few minutes of being in the city. My parents always acted so freaked out by it for no good reason. Seattle isamazing. Before dinner we had found a store selling nothing but fancy olive oils and olive oil–related products. And we got to pick between a million restaurants with a million different kinds of food, as opposed to our boring suburb of Tahoma Falls, which had a McDonald’s, a Taco Time, an okay diner, and a Red Robin for the nights we wanted something fancy. The light posts on every corner were always thickly papered over with advertisements for parties, music, shows, and benefits for extremely cool people.

In fact, there was an interesting flyer pasted onto a pole right above eye level. I stared at it as Dad and I waited to cross the street. It showed a woman with eye-popping makeup in a bright zigzag-striped dress, surrounded by shirtless boys. The rainbow text was yelling at me to go to a “Pre-Pride Drag Brunch,” and even though I didn’t know what any of those words meant, it was a very convincing advertisement.

Well, okay, I did know what all of those words meant, but not necessarily in that order. “Pre” means before, and “pride” means, like, feeling good about yourself. I knew what brunch is, we got it sometimes on Sundays at the diner. It’s breakfast but later. And “drag” means to pull something behind you. Or something hard and bad, but that’s mostly old-fashioned slang, like “don’t be a drag, man.” So that meant “pre-pride drag brunch” was a late breakfast you kind of pulled yourself into before you felt good about yourself. That maybe made sense? But I wondered if there was some context I was missing. My teacher last year always talked about using context clues to improve your reading, so I decided to ask my dad. Literacy is important.

“Dad? What’s a ‘Pre-Pride Drag Brunch’?”

I already knew his mood had gone from good to . . . something else, so it wasn’t a surprise to see his jaw tighten. He glanced at the poster and widened his eyes, his nostrils flaring slightly. “Pre-pride brunch is why we don’t come into the city much,” he said. Then the walk signal changed from a red hand to a walking man and he bolted across the street, his not-very-long legs pounding his dismay on the crosswalk.

I skipped to keep up. I knew it would be useless to ask any follow-up questions, but I couldn’t help myself. “What does ‘pre-pride’ mean? I know what ‘pride’ is, but I’ve seen that word all over the place lately. Is everyone constantly overjoyed to be a Seattleite?”

I liked that word, Seattleite. I wanted to be a Seattleite someday. Much better than being stuck as a Tahomaite forever, and people from our town didn’t even call themselves that. Which made sense; “Tahomaite” sounds like a disease.

Dad pinched a little bit of beard between his fingers and tugged on it. He always did that when I asked him a tough question, or when he was unsure of something. After a minute he released the poor tortured hairs and said, “Well. You know what ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ are. Right?”

Oh. Yeah. Pride pride. How had I missed that?

“Right,” I agreed. I didn’t really need him to explain any more, but I hoped he would. I was curious what he would say. My parents didn’t talk about stuff like this much.

“Pride is for them,” he continued. “For those kinds of people. A parade. It celebrates an important day in their history. It happens in June, so all these posters and signs are out of date. They should get someone to take them down.”

That seemed like all he was going to say. Brief, and correct, and not nearly enough information, which was about right for my father when he didn’t want to talk. But there were still some parts I wasn’t sure about, so I risked a few other question.

“So, is ‘drag brunch’ brunch with drag queens? I’ve seen drag queens on TV, are they also waitresses? That’s cool, I want a drag queen to bring me pancakes, can we do that sometime?”

He shrugged, which was probably a “no” to that last question and an unsatisfying answer to the others. I wanted to run back to the flyer, not for the shirtless boys but because I realized that the woman in the bright dress and amazing makeup was a drag queen and I wanted to examine her more thoroughly, but we were already a block away and there was no way he’d let me go back. Oh well. Someday I’d come down to the city on my own and no one could stop me from doing whatever I wanted.

I had other questions, but I could tell he had said all he was going to. If Mom were here I would have asked them; she always gave me much more helpful answers. Like when I asked where babies came from, Dad stuttered and turned red and played with his beard while Mom told me everything about sperms and eggs and uteruses and all that. People always say I look exactly like my dad, but I have my mom’s sense of humor and love of bright clothes and accessories, so being a mixture of both parents made sense to me. But if I asked Mom to tell me more about Pride, she might tell Dad. And then they’d wonder why I was so curious about the topic. So I had to be satisfied with that tiny bit of information.

I said a silent goodbye to “the city.” It’s about a forty-minute drive from Seattle to Tahoma Falls. An hour and a half if traffic is bad. But it would feel ten million hours long if Dad insisted on listening to his sad-girl-with-guitar music or talk radio the whole way, and that would be intolerable while I was buzzing from ice cream and the city and the poster and maybe some nerves about the first day of school. “Father-daughter bonding time” was his idea, so he would have to deal with the fact that I could not be quiet and introspective the entire ride home. I waited for us to get in his pickup truck (hot as an oven inside, I yelped when my thighs touched the fake leather of the seat), and started talking once Dad got onto the freeway heading north.

“I can’t believe it’s my last year at the Lab!” I began. My school was called the Tahoma Falls Collaborative School, but we called it the Lab for short. “I remember when I was a kindergartner and the sixth graders looked so huge. Like, basically grown-ups. And now I’m going to be one of those basically-grown-ups, but I feel like exactly the same person that I was in kindergarten! And everyone in my class seems the same too. It’s so weird. And now I’m like, ‘Wow, middle school students are so big and old,’ but I bet that once I get to middle school I’ll have the soul of that same kindergartner. Does that ever go away? Will I get to college and still eat my broccoli pretending that I’m a dinosaur eating trees? Or is there some magic point where you become an adult and stop feeling like a kid inside?”

I on purpose left that as both a question and a comment to see if Dad would take the bait and start talking, and if not I could keep going without making it awkward. He let out a “mm,” so I decided to keep going. I didn’t think it was a mad “mm,” maybe an I-don’t-know “mm.” Or even an I-do-know-but-I’m-not-going-to-tell-you “mm.”

“Although I guess I did start feeling older last year,” I continued. “Because you know how we mostly stay in our classroom but we also move around for, like, P.E. and music and library? We started calling those ‘first period’ and ‘second period,’ it even says that on our schedule. That did make school different, saying ‘What do we have for second period’ like high schoolers do on TV. Even though the boys laughed at first because we were talking about periods. Do they ever get more mature about that, also?”

That was definitely a question that he could and should respond to, being a boy and all, but it was maybe unfair because Dad got embarrassed talking about those kinds of girl things. Like when Mom bought me my first training bra a few months ago, we were at the mall and she told him why we had to stop by the Target. He stopped dead in his tracks, saying that he had to go to the hardware store and would meet us at the car.

And sure enough he tugged on his beard, cleared his throat, and said, “Not as far as I can tell. Sometimes guys get comfortable talking about that kind of thing, but that won’t happen for a while. And plenty never get there at all. Sorry about it.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “And actually I can see this being a good thing? If there’s ever a guy bothering me and I want him to go away, I can say ‘Oh man I got my period yesterday, so funny how it’s blood but also doesn’t hurt, you know?’ and then he’ll run away like a scared little bunny. Ooh, this could be a lot of fun, what if I started doing that? Not even if they’re bothering me, just to make them uncomfortable? No, that’s mean. Oh well.”

Dad hadn’t stopped tugging on his beard, and I felt a little bad. He was obviously one of those guys who would have run away.

He cleared his throat. “Have you, uh, started. Yet. Or would that be a joke?”

“Omg. Dad. You don’t even know? I promise that once I get my period, I’ll tell Mom, and she’ll tell you. Did you think that had happened and you didn’t know?”

He shrugged, both hands on the wheel. “It’s your business. Didn’t want to assume you’d tell me. But you can. You don’t have to go through your mom.”

“Really?” I tried not to sound so surprised, but his lips quirked up in a smile; he had to see why this was a shocking development.

“Really,” he said. “I know you’re growing up. You’ll be a teenager soon, and I want you to be able to talk to me too. About anything.” He cleared his throat. “Like your feelings, your friends. Any boys you have crushes on.” I’ve always loved his voice; it’s light and reedy, but I’d never heard it like that, almost rough.

There was something I could have said then. About boys, and crushes on them. How I might never have one. And that I didn’t know why. But I held back. “Well, thanks, Dad. I’ll probably value Mom’s opinion about pads and bras and that kind of thing more, but I’m sure we’ll find other important coming-of-age topics to bond over! Maybe once I hit high school, there will be boys worth having crushes on, and your male insight will come in handy.”

Probably not, a little voice whispered at me, but I told it to hush. Because Dad smiled and nodded, then turned up the radio. Because we finally did “bonding” right, for once, and I wanted to keep it that way.

chapter 2

“What do I wear on the first day of school of my last year at school?” I yelled down the hall.

“Clothes,” barked Dad, unhelpfully. But I wasn’t asking him.

“Moooooom! Help me pick out my outfit!”

“You don’t need my help, Annabelle, you’ll look beautiful no matter what,” Mom called back. “And we have to go.”

“Please?” I hollered. “I am suddenly overwhelmed by choices!”

Yes, I should have figured out my first-day-of-school outfit before the first day of school. But in my defense, there were so many first-day-of-school decisions to make. What kind of binder to get, whether or not I needed a new backpack (I said yes, Mom and Dad said no, we compromised and Mom helped me sew some cool patches onto my old one: unicorns and shooting stars and emojis), and also since I didn’t have our class schedule yet, there were so many unknown factors! What if I wanted to wear the shirt that goes with my green Converse but I also wanted to wear my green Converse tomorrow because we’d have gym class, but I didn’t want to wear them two days in a row? Or what if I decided to wear my absolute best outfit today but everyone else dressed normally and it looked like I was trying too hard? But what if there was a cool new kid and this was my only chance to make a first impression?

Well, that last one wouldn’t happen. People didn’t move to Tahoma Falls often, and the kids that I’d be graduating with had been my classmates since kindergarten. A few joined in first or second grade, but the rest of us had known each other since we were babies. Our class used to be twice as big, but the younger grades are always bigger than the older ones. People move away, or go to different schools, and I guess “small class size” is something that parents think is important, but I wouldn’t mind more choice when pairing up for group projects. So the odds of someone new joining in the sixth grade? Maybe in a movie, but not in real life.

I pulled a bunch of things off the hangers and threw them onto my bed. Mom thumped down the short hallway, and of course when she came in my room she was already perfectly dressed in a knee-length orange sun dress, bright red lipstick, and my favorite pair of her glasses, the magenta cat-eyes with rhinestones.

My mom and dad are total opposites in every way. And I know they say that opposites attract, but they’reso different that it was hard to imagine them ever attracting each other. Like, my dad only ever wears dad jeans, which means “out of style.” He might wear a T-shirt if he’s working in the garden, but otherwise, it’s jeans and a button-down. Button-up? Anyway, a plain shirt with buttons. So boring. Whereas my mom always, always, always wears dresses. I think I’ve seen her wear pants three times in my entire life. And the dresses she prefers are like lush tropical flowers, eye-catching and surprising and able to turn any room into a party.

And they’re the exact opposite physically too. For most of my friends, the mom is shorter than the dad, and the dad is generally bigger than the mom. Not in my family! My mom towers over my dad, especially when she’s in heels. And it’s not only that Dad is short and Mom is tall. My mom is like one of those old paintings of rich ladies, all hips and belly and boobs. While my dad is like a blade of grass, sharp shoulders and a sharp jaw and a belt always cinched to the last hole.

I was waiting to see which one I’d take after. For now, in addition to having my dad’s eyes and nose, I was also on the smaller side, hoping for a growth spurt. I’ve always wanted to fill up a room the way my mom does, but I guess there’s more than one way to do that.

“You haven’t let me dress you since you were four!” Mom remarked as she came into my room. “What’s going on?”

“I don’t need you to dress me, but this is a special occasion and I could use your expert eye! Is that too much to ask?”

She laughed. “I suppose not. And it’s nice to know I’m not irrelevant yet. But everyone in your class has known you since kindergarten, so I’m not sure why this is such a big question. Pick one of the new outfits we got for you over the summer, they’re all perfectly nice.”

“Mom!” I huffed. “Don’t you get why it’s important to start off on the right foot? It’s a new year in the oldest class in the whole school! A new me! I don’t know exactlyhow it’s a new me, but I want it to be, so let’s pretend anyway.”

“Okay, okay,” said Mom, putting up her hands in surrender. “So the question is, do you want to go in and make a big statement right away? Or begin as more of a blank slate, so you can evolve into a style as the year progresses?” She walked over to my closet and started pushing hangers aside.

I mulled over my choices. That was a good question. No wonder Mom always looked perfect. “Can I go with something in between? Not a boring blank slate but also not ‘Annabelle Blake, fashion icon’?”

Mom groaned. “You couldn’t have thought this over yesterday? Okay, we’re going for interesting but with plenty of room to grow. How about your denim skirt and this flouncy top?” She held out a shirt that I would describe as more ruffly than flouncy.

“The denim skirt has not fit me in six months, you know that!”

“I didn’t buy you a new one?”

“. . . Also I didn’t like my denim skirt.”

“Fine. Okay, your pink overall dress and a white shirt underneath.”

“No, that screams that I’m a girly girl, which would be okay as one outfit out of a lot of outfits, but not as the first one of the year.” I hopped off the bed to join her in front of the closet, frustrated that nothing seemed quite right, and then inspiration struck. “How about my yellow capris and the forest shirt?” I pulled them both out and held them against me.

“Perfect. Beautiful. See, you didn’t need my help after all. And now you have two minutes to get your yellow-capri’d butt in the car.”

I threw on my outfit, which was super cute, grabbed my backpack, bounded down the porch steps, and was in the car in three minutes. Mom was already waiting for me, engine idling, and Dad waved at us from the door.

I started walking myself to school last year; it only took twenty minutes, there weren’t any big hills, and driving is bad for the environment. But the Lab was on the way to one of my mom’s early clients, and she said that her baby only started sixth grade once. She worked for a program like Meals on Wheels, helping old people keep themselves fed, which meant that my lunch was always balanced and nutritious.

And honestly, I was glad for the ride. It was the hottest first day of school I could remember. Not that I had a cataloged memory of every first day of school and how sticky I was on each one, but global warming is a thing. I told myself that one short car ride wouldn’t make much of a difference in the overall life of Planet Earth, and I didn’t want to sweat through my deodorant before the day even started (I started using deodorant this summer, I hoped everyone else did too).

I watched the same old scenery scroll past me, trees and ivy-covered ditches and identical split-level houses, and sighed. School was fine, mostly. We called a lot of teachers by their first name, and parents were encouraged to volunteer in the classrooms or even teach special lessons. In the second grade we learned about embryology by hatching duck eggs, and also learned about how farm-to-table restaurants work because some kid asked what happened to the ducks we sent back to the farm once they got too big for the classroom. That was a sad day for Peepers, Quackers, Spots, and their siblings, but also my mom made duck for dinner once a year around Christmas, and ducks are delicious, so I couldn’t feel too bad about it. We only ever took tests when we had to because the state made us for funding or whatever, and we never had to do boring stuff like reading a textbook and answering questions at the end. I only knew what textbooks were because sometimes teachers talked about how lucky we were not to have them.

The Lab was started by a bunch of parents a million years ago. Back then, there wasn’t a public school in the area, and they didn’t want to drive for hours every day. Now there is one, of course, but the Lab is smaller and closer to our house, and when it was time for me to start kindergarten my parents talked to people who had kids there and they liked the set-up.

Sixth grade was supposed to be fun. Rumors had circulated for years about what our last year at the Lab would be like—ice cream parties every week, unlimited library books, more field trips, generally being the bosses of all the little kids. Caroline, the sixth grade teacher, had been there since before I was born, and everyone talked about how nice she was.

But I was more excited about the end of sixth grade than the beginning or the middle. I wanted to graduate, and get out. The Lab was fine, but I was getting tired of fine. In the same way that Tahoma Falls was a perfectly nice place to live, but “perfectly nice” had started to become code for “boring.” If I was too young to go to Seattle by myself, I at least wanted to start middle school, where some things would be different.

But before I could work myself into a funk Mom pulled up to the collection of low, flat-roofed buildings that didn’t quite fit together but would be my educational home for one last year. She kissed me on the cheek, I grabbed my backpack, and I zoomed out the car. The year couldn’t end until today started, and I was more than ready for it.

chapter 3

As I approached the classroom door, the tiniest part of me held out hope thatsomething interesting would happen. Like maybe a swirl of blue jays and hummingbirds would accompany me into the room, or I would all of a sudden learn how to walk in slow motion with the wind dramatically blowing my hair back. Or I’d open the door into my face and start the year with a bloody nose, because at least that would be a story. Instead I walked through the doors without a problem, and discovered that the sixth-grade classroom looked exactly like the fifth-grade classroom: desks arranged into groups of four, a library nook, a rug in front of the smart board, a big closet for teacher supplies. I hadn’t been expecting a space-age set up, but they could have spruced it up alittle.

“Good morning!” a voice chimed from behind me. “What’s your name?”

I turned around. Instead of staring up at Caroline, who was very tall and usually wore blouses and skirts, I was right at eye level with a woman with hair cut in a cute bob, a bright orange scarf twined around her neck over a dark purple shirt, and black jeans.

“Where’s Caroline?” I blurted out, before remembering that it was probably a bad idea to be rude to the person who was going to be grading my homework for the rest of the year.

But she didn’t seem offended. Her laugh sounded like the bubbles you blow in a milk carton, delighted and fresh. “I’m Amy. Caroline got sick over the summer, unfortunately, so I’m her replacement. We sent an email to the families, did your parents miss it?”

One thing my parents loved to complain about was how many emails my school sent. “When I was a kid my parents figured school would keep me alive and that was about it,” Dad griped sometimes. I don’t think he’d set foot on campus since dropping me off for the first day of kindergarten. Mom paid attention, sometimes, but she only went to the parent-teacher conferences they scheduled twice a year, no school board meetings or parenting discussion groups or anything, so I wasn’t too surprised to hear that they had entirely missed some big announcement.

“I guess so! But, it’s okay, I like surprises. I mean I don’t like that Caroline is sick—that’s sad and I hope she’s okay—but we’ve all known each other forever, so it’s cool that there’s at least one new person in the room.”

Amy smiled. I couldn’t tell how old she was because she looked like an adult, not a teenager or a senior citizen. She was definitely either older or younger than my parents. Maybe thirty? Or forty? Probably in between those two numbers. “You never did tell me your name,” she reminded me.

“Oh! Sorry. Annabelle.”

She picked up the class list from her desk. “Annabelle Richards or Annabelle Blake?”

“Blake. Annabelle B. That kind of sounds like Anna Belby, which I don’t want to be called, so maybe you could call her Annabelle R.? Sometimes teachers call both of us by our full names but that’s a lot of syllables to say every time. Maybe she’s decided to go by Anna or Belle or her middle name over the summer.”

I hoped so. Us having the same name always bugged me. Not because she’s a bully or a teacher’s pet or anything that bad, really, she just never seemed quitehere. It’s hard to explain, but talking to her always made me feel uncomfortable. She was so clearly in another world, you could never tell if she understood what was going on. And I don’t want to sound mean, but she chewed her hair a lot, so it was always kind of wet and clumpy. She never paid attention, so whenever she asked questions it was usually something the teacher hadjust said. It wasn’t a big deal, no one ever got us confused, but I still wanted to be the only Annabelle in my class.

And right on cue the other Annabelle walked in. She always dressed like her mom picked out her clothes, without realizing that her little girl had grown up. Sixth grade didn’t seem to be any different. She was wearing orange sweatpants, and a yellowish shirt that used to be white with a bunch of Disney princesses on it. Amy introduced herself, and the other Annabelle blinked a few times, said hi, and that her name was Annabelle (dang it) and looked around for the desk with her name on it.

“Where am I sitting?” she asked slowly.

“Oh, I haven’t assigned you seats yet!” Amy said. “I want to get to know you all first. We can figure that stuff out as we go along. Go ahead and find a spot anywhere.” The other Annabelle put down her Frozen backpack, the same backpack she’d had since third grade, at the desk closest to the back of the room. I was glad I hadn’t picked a seat yet, so I wouldn’t have to sit at the same desks as her.

I put my backpack down at the desk diagonal from Sadie, closer to the front. Sadie wasn’t my best friend or anything; my best friend had been this girl named Franka, but she moved away last year. So now Sadie was my favorite person in my grade. We had gone to the mall a few times over the summer, and she was wearing one of the outfits we got together.

“Annabelle! Hi! How was the rest of your summer? Can you believe Caroline is gone?”

“Sadie! Hi! Good! Yes!” I said, answering her questions in order. We compared new school supplies as the other kids in my class started to trickle in.

Johnson set his green backpack topped with a fin of dinosaur scales on a desk across from the other Annabelle, then came over to ours to say hello.

“Hi Johnson!” Sadie exclaimed. “What did you learn about over the summer?”

“Well,” said Johnson, “I got a Lego set for my birthday that forms an M22 Locust, a lightweight tank used during World War Two. They were airborne and weighed only seven-point-four long tonnes, a British unit of measurement that is one thousand kilograms. Sherman tanks were the most popular, but I decided that M22s are more interesting.”

Johnson’s lecture probably sounds annoying, but there was something deeply delightful about his excitement. He articulated each letter perfectly, only sometimes spitting on the “s”s. He sometimes sounded like a robot reading from an encyclopedia, but he also laughed a lot, and was a good person to team up with on group projects. He was definitely weird, but in a way I liked better than the other Annabelle’s version of weird.

As opposed to Dixon, who strutted in right after him. Dixon wasn’t weird at all, and that isnot a compliment. He was wearing what looked like a brand-new outfit from one of the more expensive stores in the mall. A red polo shirt, crisp black jeans, white sneakers that I would probably recognize if I was the kind of person who paid attention to boy sneakers.

He was objectively the cutest boy in class, or at least the one who looked the most like a magazine cover with his curly blond hair, dark blue eyes, a nice chin, and dimples that came out when he smiled. Also, I hated him.

Adults are always saying “‘Hate’ isn’t a nice word!’ and I know that, which is exactly why I use it to describe my opinion about Dixon. He’s the type of boy who knocks things out of girls’ hands and then have a nearby grown-up say, “Oh that means he likes you.” My parents say that that’s the kind of liking I can do without. Once, he decided that random words like “doughnut” or “tadpole” were insults, and then spent days calling Felix and Jonas and Patrick doughnuts and tadpoles until they exploded, and then defended himself saying “but those aren’t even bad words” even though he knew it was going to upset them. He’s the worst.

Dixon dropped down his backpack at an empty pod and yanked his desk out a little bit, so it wasn’t touching any of the others. Then he sat down in his chair and immediately tipped it onto the back two legs, which teachers always tell us not to do.

“ ’Sup?” he said, nodding in our direction, in a tone of voice that he clearly thought sounded cool. And maybe it did sound cool; I didn’t know and also completely didn’t care. But maybe he got nicer over the summer? Like he had some transformative experience at camp where he learned the true meaning of friendship and why you should be nice to other kids even if you can get away with being mean.

“Hi, Dixon,” said Sadie, not quite looking at him.

“How was your summer?” I asked. I was not, in fact, curious about his summer but figured that starting the year off on the right foot couldn’t hurt. Especially in front of a new teacher.

“It was great!” he said. “My parents took me to Europe. I loved Athens and Rome. They’re the birthplace of civilization, you know.”

“If you say so,” said Sadie, rolling her eyes. Her parents had moved here from South Korea, which definitely has civilization and is very far away from those random cities. So much for the right foot. I waited for Dixon to ask us about our summer vacations or what we thought of the new teacher or literally anything, but he just wandered over to Johnson’s desk, probably to try and outsmart him about something. After a minute, we heard Johnson interrupt Dixon to lecture him about different theories surrounding the fall of the Roman Empire, which cracked us both up.

We had a few minutes before the day officially started, so I decided to get my desk in order. I placed my new binder with its colorful subject dividers in the center, and arranged my pencils, pens, and erasers, and a package of multicolored Post-its around it. I was deciding what to do with my highlighters (I literally never use them and also they’re important to keep on hand in case I find something that needs highlighting) when I heard the door open again. I looked up reflexively, curious about who had shown up, and did a double take. The kid coming through the door was no one I had ever seen before.

My brain spent a few seconds ricocheting around the question “Is that a girl or a boy?” First I was like “Oh my gosh there’s a new boy, where did he come from?” And then I was like “Wait, hang on, I think that’s a girl with short hair? She looks so cool!” But then I wasn’t sure, about anything.

Except I was sure that their shoes were amazing. They were white, and made of some shiny fake leather or whatever, and the new kid had clearly decorated them at home with markers. The shoes didn’t match, exactly, but they both had eyeballs and rainbows and peace symbols and shooting stars, things like that. Definitely the coolest ones I had ever seen.

The new kid was also wearing a T-shirt with the words “Hedgehogs: Why don’t they share the hedge?” and a picture of two hedgehogs standing next to a strip of green, with a word bubble coming from one of their mouths saying “no.” Before the kid even introduced themself to Amy I burst out into laughter.

“That is the best shirt I have ever seen!”

“Thanks!” they said. “I love your forest shirt!”

“Yeah well, I also love your shoes, and my shoes are fine but not nearly as cool as yours, so I win the compliment battle. So there.”

“I’ll take it,” said the new kid, and their laugh was like a rare bird had flown into the room and perched on my desk.

Amy glanced down at the attendance sheet. “What’s your name, friend?”

“Oh, hi, I’m Bailey. Bailey Wick.” Of course they would have the coolest name I’d ever heard.

“Oh, you’re the student who enrolled over the summer, right?”

“That’s me! We just moved here. My parents heard good things about this school and figured one year at the Lab was better than none.”

“We’ll have to compare notes,” said Amy, bubble-laughing. “This is my first year teaching here. Choose any seat you like.”

Bailey came over to our pod. I wriggled with excitement.

“Hey, I’m Bailey. I mean, I know you heard me say that to the teacher, but it’s the best way to start a conversation with people you don’t know.” They put their hands on the desk across from me. Purple polish adorned their neatly-trimmed, square fingernails.

“I’m Sadie,” said Sadie.

“I’m Annabelle! How long have you been in Tahoma Falls? Where did you move from?”

“We got here a few weeks ago,” they said, sliding into the open seat. I tried not to stare. Tried to look at them like I would any new kid, not an especially cute one that I couldn’t tell was a boy or a girl or—“From Seattle. My parents wanted a change of scenery, I guess? I’m not sure why they picked Tahoma Falls over, like, Bellingham or Snohomish or Issaquah, but this place is fine so far.”

“My parents always act like Seattle is on the other side of the world,” I said. “Did you grow up there? That must be so cool.”

“I guess it’s cool? I already miss Seattle but my friends and I talk a lot, and it’s not like we moved to Wenatchee or Spokane. We can still visit each other. Honestly, it feels weird to not be on Capitol Hill surrounded by ramen shops and drag queens, it’s all I’ve ever known.”

Drag queens. Hang on. “Have you been to drag brunch?” I blurted out. “What’s it like?”

Bailey did a double take, which made sense because that wasn’t exactly a normal question to ask when you’re getting to know someone on the first day of school.

“Um, yeah, a few times? It’s just brunch, but with drag queens as waitresses giving shows and stuff. Why?”

“The last time I was in the city with my dad,” I said, trying to sound casual and sophisticated, like we went to Seattle all the time, “there was an ad for something called ‘Pre-Pride Drag Brunch’ and he refused to explain anything about it.” It’s hard to sound casual and sophisticated when you don’t know something.

“Oh! Yeah, drag brunches happen all the time at Cherries, but a lot of other places have them during Pride. It’s fine, I guess, but honestly I don’t want a show when I’m eating. Gotta focus on my waffles, you know?”

“Totally,” I said, because waffles are serious business. Sadie also nodded in agreement, but I bet you anything she had also never been to a restaurant that had a drag queen showtime.

I was going to ask another clarifying question about what exactly happened during a drag queen show in a restaurant, but a chime rang through the classroom causing the chatter and motion to die out all at once. The rest of my class had shown up while I was talking to Bailey, and Amy was standing at the front of the room. It was time to begin.

“Good morning, sixth grade!” she said. “Let’s get started. Everyone find a spot on the rug.”

It turned out that even sixth graders had morning meeting. When we were little it was pretty basic, going around the circle and saying good morning to everyone, reading the schedule for the day, checking the weather, that sort of thing. It got more interesting the older we got; sometimes we’d talk about current events or have a show-and-tell or play fun games to start the day. I wondered how different it would be this year.

All twelve of us found a spot on the rug. I sat between Bailey, who smelled pleasantly like Cheerios, and Jonas, whose curly brown hair stuck up several inches above his scalp. There were no other surprise classmates. Loud Olivia, who always acted like she was in charge. Amanda, who used to throw a lot of tantrums, but in third grade started helping Jonas recover from his. Patrick, who always got upset when something was unfair, know-it-all Audrey, bookworm Charlotte, and Felix, who was always goofing off. And then I wondered how they would describe me—Annabelle who talked more than the other Annabelle? The girl who knew way too much about hungry old people because of her mom’s job? Annabelle with the cool, colorful outfits? Or maybe what they thought about me were things I didn’t know about myself. Huh.

Amy sat cross-legged on the floor and took a deep breath. “Welcome to the first day of school,” she began. “I know you were all expecting Caroline to be your teacher. She was the sixth-grade teacher when I went here, believe it or not. So it’s a little strange to try and follow in her footsteps, but if we all work together, I know we can build our own special community.”

“Wait, you went to school here?” asked Charlotte.

“Sure did! I was a Lab lifer, kindergarten through sixth. I’ve only ever taught in public schools, but I’m familiar with how this place is run. Maybe too familiar,” she added with a chuckle. “Let’s start off the year by going around and sharing your name, the best part of your summer, and one goal you have for this year. Patrick, would you go first?”

Patrick was sitting directly to her left. “Uh, okay,” he said, his cheeks turning red. “My favorite part of the summer was when we went hiking at Mount St. Helens. And my goal for the year is to . . . um . . . not eat anything with palm oil in it. Because to get palm oil you have to cut down palm trees, which is bad for orangutans, and I care about orangutans.”

“Thanks Patrick, that’s great. Audrey? You’re next.”

I’d probably spent a million hours of my life being part of a circle-go-round where we each say one thing. It totally made sense why teachers had us do this kind of thing. The problem is that instead of listening to the kids who go before me, I always spend the whole time rehearsing and planning what I’m going to say. And then after I share I spend the rest of the time going over what I had said, wondering if I could have said something better, and worrying that I had forgotten to say the most important thing, whatever it was. So it doesn’t matter if I go first, last, or in the middle, I never pay attention to what anyone else was saying. By the time it was my turn, I vaguely remembered Charlotte saying that her goal was to learn calligraphy, and Dixon repeating again something about the birthplace of civilization, but I hadn’t thought of anything interesting to say.

“My favorite part of the summer was going berry picking in Carnation and then making pies and jams and stuff with everything we got,” I began. If I was being honest I’d say, “I don’t have a real goal because all I want is to get out of here,” but that would be a downer, so I said, “My goal for the school year is to get ready to move on to middle school,” which was practically the same thing but a nicer way of phrasing it.

Bailey was up next, and, for once, instead of worrying about what I just said, I focused on their every word.

“Hi! My name is Bailey. My parents and I moved here three weeks ago, so I guess my favorite part of the summer was the goodbye party we had in Volunteer Park. My goal for the school year is to be more of an animal advocate—Patrick, I want you to tell me more about palm oil! Oh, also, my pronouns are they/them.”

I had no idea what that meant and cocked my head curiously without meaning to. Bailey glanced in my direction, then quickly turned away. For the first time since striding into a brand-new school with brand-new kids, they looked nervous. Confusion spread over a lot of faces, but not Amy’s. She was grinning widely.

“Bailey, thank you for sharing that. I’m noticing that some of your classmates could use an explanation about what you mean. Do you want me to try to explain, or would you prefer to?”

Bailey narrowed their eyes. “How about if you go first, and I’ll add anything you miss?”

Amy laughed. “I love a test. Okay. But first, who can tell me what a pronoun is?”

Johnson, Charlotte, and Dixon raised their hands, but Olivia yelled “He, she, or it!”

Amy ignored her. “Johnson, can you share what a pronoun is? Olivia, raise your hand next time.”

“A pronoun,” Johnson enunciated carefully, spitting a little on the “p,” “is how you refer to something or someone when you are not referring to them by name. A chair’s pronoun is ‘it,’ so you could say ‘Can you pick up your chair and moveit to the rug’ instead of ‘Can you pick up your chair and move the chair to the rug.’ For people we use ‘he’ or ‘she’ instead of saying their names all the time, because it is a more efficient use of language.”

“Correct,” said Amy. “So, the pronoun ‘they’ can be used for a group of people, but it can also be used for one person, if you’re not sure what pronouns that person uses, or if that person’s gender isn’t easily described as ‘he’ or ‘she.’ Bailey, how’d we do?”

My head was spinning. This might have been the most educational morning meeting of my entire life. Even though I was left with a million more questions than I started with. Meanwhile, a huge grin spread across Bailey’s face as they said, “You got it! I’m nonbinary, so I go by ‘they’ because I’m not a boy or a girl.”

I looked around to see what everyone else’s reaction was. The other Annabelle was picking at something stuck to the sole of her shoe, shoulders hunched up around her ears. Sadie and Patrick were nodding like this was something they already knew about. Everyone else looked either confused or interested. Dixon was the only one with a Look on his face, like he was saying “yeah, right” on the inside.

What did my face look like? Probably more confused than Audrey, who always pretended to know the answers even if she didn’t. Hopefully nicer than Dixon’s. At least I was paying attention, unlike the other Annabelle. But honestly? I still didn’t understand. Did Bailey mean that they were, like, born some kind of way that wasn’t boy or girl? Or that they didn’t feel like either? Did they feel like a little bit of both or nothing at all? Is that why I couldn’t stop staring at them? But as these questions popped up in my head Bailey was still talking, so it was probably a good idea to shut myself up and listen.

It turns out that Bailey wasn’t answering any of my burning inquiries. They were saying that they started going by they/them pronouns last year, and that a few of their friends in Seattle were nonbinary too, and then their turn was over.

As Felix started sharing, I realized: I hadn’t thought of Bailey as “he” or “she” at all! My brain was like, oh you don’t know that person’s deal? Better go with “they” till you find out. And then I found out! And I was right! My brain is a genius sometimes. I mentally high-fived my brain and then wondered what it would feel like to physically high-five your brain. Probably sticky. Ew.

Anyway, sorry to Felix, but I did not listen to a word he said, and I also didn’t hear what Audrey’s goals for the school year were, but it was probably something ridiculous like “Build a garden on the roof” or “Memorize an entire Shakespeare play.” Then it was back to Amy.

“Thanks, everyone. I’m so excited to get to know you all better during the year!” She twisted to the smart board to look at the schedule. “Okay, the first part of our day is math. We’re going to—”

Before she could say more, Dixon cut her off, which usually would be okay because I love any excuse to avoid math, but I could tell from the impatient way he raised his hand that it wasn’t going to be good.

“Quick question,” he said. “Bailey, which bathroom are you going to use? I mean, I know you say you’re not a binary or whatever, but on some level you reallyare a girl or a boy, so. Which one? Just so we know.”

“What are you talking about?” yelled Olivia, before Bailey or Amy could respond. “Every classroom has its own one-person bathroom, and then there are one-person bathrooms outside the gym and the library and everything. Youknow this! You’ve been here almost as long as the rest of us!”

Usually teachers shut Olivia down when she starts calling out, but Amy looked amused. “That’s true, Dixon, so there’s no reason to worry. I’m sure Bailey appreciates your concern for their well-being.”

“Yeah, thank you for your concern,” said Bailey archly, one perfect eyebrow raised. “That was one of the reasons we decided that I should go to this school anyway, the public school only has one bathroom that isn’t gender-segregated. And also, you obviously want to find out what I was assigned at birth, like whether I have an ‘M’ or ‘F’ on my birth certificate, but that’sso none of your business. Sorry not sorry.”

And just like that Bailey proved that they were the amazing-est person ever. Not because of the gender thing, but because anyone who could make Dixon turn that shade of bright red was someone I needed in my life. But also, some guilt wormed its way through my stomach because I kind of had been wondering what Bailey was. I mean, I knew they were nonbinary, but like—and then my brain started yelling that it was rude of me to wonder, and that it wasn’t any more my business than it was Dixon’s, and I should probably shove all of those thoughts into a box and pay attention to the math lesson that had just started.

By the end of the period it had become impossible to imagine my new classroom without Bailey. My eyes kept wandering over to them; they already seemed familiar, but it was still exciting to see a new face.

After second grade we were allowed to eat anywhere in the classroom, not only at our desks. I weighed my options and decided on the corner that had bookshelves, a softer rug, and pillows. A few kids stayed at their desks, but everyone else spread out in that general area of the room.

“Olivia, your hair looks so good with that color,” said Amanda, reaching out to stroke a lock dyed bright pink.

“Thanks, babe,” said Olivia. Those two had switched between best friends and worst enemies for as long as I could remember.

“So, Bailey!” Audrey exclaimed. Her eyes were magnified behind her thick glasses, which matched her constant, aggressive curiosity. “It’s so interesting to have someone new in our class! The last person to join was Dixon, and that was four years ago. There used to be more kids, but obviously people move away, go to other schools, you know. What was your old school like?”

“So far? Not too different from this one,” they said, carefully peeling a string cheese with nimble fingers into the thinnest possible strands. “We had morning meeting, and our schedule looked a lot like yours. Small classes, except we always had two teachers. We also had a lot of groups! What kinds of things do you all have here?”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “We have library, and art, and gym, and . . . I don’t know what else.”

“I mean, what kinds of . . . I dunno, not-school things do you have? Clubs or whatever? Like, two years ago I started the Cool Animal Friends at my school. We met once a week at lunch and talked about whatever cool animals we learned about, like pygmy jerboas and slow lorises. And we had a bunch of after-school groups, a makerspace, a chess club. An affinity group for kids of color, of course. And I was also part of the Rainbow Club, for all the LGBTQIAP+ kids.” There was a lopsided smile on their face, like some good memories were washing over them.

“Ell . . . gee . . . what?” asked Jonas, his brow furrowed.

“I know what LGBT stands for!” exclaimed Audrey. “Lesbian. Gay. Um . . . bystander? Transgender.”

Bailey started laughing. “Bisexual! Not bystander. And then queer, intersex, ace, pan, and everything else in the rainbow.”

We Lab lifers looked at each other, and all you could hear was chewing. That sounded so different from our school. Amanda was the only Black girl in our class, after Liana’s family moved away two summers ago. And Felix was the only Latino kid. There was an Asian girl named Jamie who graduated last year, and teachers called Sadie “Jamie” more often than they should (which to be clear is never, and not only because Jamie is Vietnamese and Sadie is Korean). There were other kids of color, but they were either in younger grades or graduated earlier, and no one had ever talked about a group for them. And Audrey never let us forget that she was the only Jewish kid in the whole school.

And the way Bailey said “LGBT—” whatever, “kids.” Like they knew lots of kids like that, and not only ones with two moms or two dads. Like that was something you could be. Something you could call yourself. Something that wasn’t a big deal. Only something to have a Rainbow Club for. My stomach twisted in jealousy or anxiety or maybe something else. I stared at their shoes again, too overwhelmed to look anywhere else, and noticed for the first time that they weren’t wearing socks. Their ankles looked like smooth, tan marble.

“We don’t have anything like that,” Patrick finally said reluctantly. “Last year I wanted to get everyone to do a better job of recycling, and we even got a compost bin after I asked Principal Quinn, but I didn’t form, like, a ‘Green Club’ or anything. Maybe I could, though!”

I wanted to hear more about the Rainbow Club but didn’t want to be the one to ask about it. Patrick was onto something, though. “Could you?” I piped up, my face suddenly hot. “I don’t know about you all, but I don’t remember the first day of school being this hot. And remember last year when the forest fire smoke made the air all gross?” Everyone nodded solemnly. That had been bad. “Maybe there’s something we can do.”

I glanced over at Bailey. They were looking at me like I was someone worth looking at, and jumping started in my stomach like I had swallowed grasshoppers for lunch. “My old teachers always told me that we couldn’t fix all the big problems in the world, but we could start by making things better in our community,” they said. “Maybe we could do that here.”

The last five minutes of lunch were more subdued than usual. It had been so long since we had a new kid, and I had never seen my school through someone else’s eyes. It was a little uncomfortable.

I didn’t want to think of myself as completely sheltered. We got a newspaper delivered to our front door; I read it sometimes, and when I had to ask my parents questions, they almost always answered. But it always seemed like the problems in the world only ever happened somewhere else, to other people. And that they had nothing to do with us. But maybe that wasn’t true. Maybe my goal for the year would be more than getting it over with. When Amy rang the chime to signal the end of lunch, the room was already mostly quiet, all of us thinking our separate thoughts. The first day of school had never been so educational.

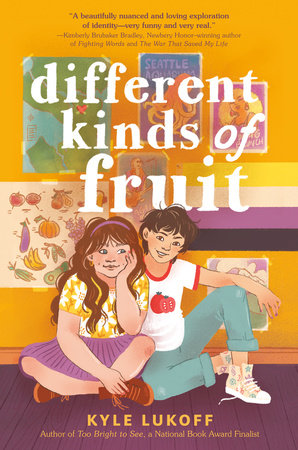

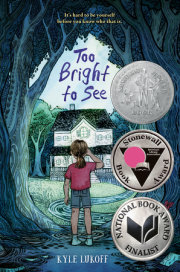

Copyright © 2022 by Kyle Lukoff. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.