INTRODUCTION

Let’s look beneath the ice-chipped surface of a fish counter at a Whole Foods in New York City. This happens every other month after closing. The customers leave, the checkout crew changes into street clothes, the store goes into lockdown to prevent its own employees from robbing them. Shifts change and the ceaseless shitty Hall & Oates music stops and is replaced by silence. Night workers, a motley rainbow of low English, low skill, low smile workers, come in, kneepads over long pants, to restock the shelves like a reverse midnight harvest. They stoop over, heads down, in their KIND bar tm shirts, or whatever other functional and empowering edible shelled out sponsorship money, kneeling there, glumly stacking yogurts. At the fish counter, the seafood team begins. Fish are removed, latex gloves gripping them two at time—fillets and whole fish, sloppy little bastards— and tossed into the plastic tubs that are their nightly home. The mussels are bagged, the shrimp scooped together into mesh cages. Next the metal trays come up. These are little more than decorative housing, and are promptly sprayed down to remove a day’s worth of sweat and oil and torn pieces of flesh that sloughed off from handling. Below the trays, a thin plastic webbing for grip, then a layer of ice: once individual chips, now grown hard as a skating rink from periodic thaws and re- icings during the day. The surface is littered with the typical debris: fish parts, crumpled-up stickers announcing wild caught!, errant cockles, cracked mussels.

Usually that would be it. Aprons would be stripped off, giant foul garbage bags of fish guts and butcher paper would be lugged to the dumpsters in the back. But on this night, the one that comes every other month or so, the case itself is cleaned. An order has come down from high, seemingly at random. And so, for the entire length of the 38- foot case, the employees hack the ice into large chunks. It is exactly like shoveling snow in the winter and they use big thick shovels to do the job. Standing up on metal platforms to get leverage, they chop straight down, chiseling out 2’ x 2’ x 2’ blocks that they then systematically take out like giant sugar cubes to be melted in the back. It is reasonably physical work and soon they are sweating. Once the top layer is removed, they begin anew on the layer below: gridding it out, chiseling, pulling out cubes. Beneath this second layer, the ice is more crunchy, less frozen. It’s an old freezer and inconsistent and it only takes a few scrapes before you get to streaks of brown. A few more and the smell comes. It is horrible and not at all of decomposition but of fecal waste maybe sweetened slightly, thick in the air like you are exhuming something dangerous, which perhaps you are. Soon after the smell, the streaks of brown darken and the ice turns with entrails and smashed pieces of shell, the shovel uncovering squid tentacles, crab antennae, all two months old, rotten, buried under there, each scrape revealing some new purple color, and the odor is such that you really cannot breathe it long. So neither team member does, instead spelling each other by rushing off to do other tasks like melting the giant cubes under hot water or just standing to the side and muttering how the fuck does it get like this?

Then, at a certain scrape of the shovel, the bottom of the case is revealed. Stainless steel. But it’s streaked green with bile, gray with pancreatic froth, pink with clam flesh, all strung out and mashed in the ice slurry. To the extent that they are recognizable, the contents are inexplicable and vaguely horrifying. No shrimp were stored in this section of the case, so why the rotting pile of shrimp casings? No whole fish either, so why the set of red lacy gills? Months of slow melting and cracks in the ice and the chaos of retail have allowed it all to accumulate down there in a weird gutter of seafood waste compressed beneath four and a half feet of ice.

Eventually the ice and slime are removed and a high-blast hose with a separate nozzle for green concentrated soap is sprayed against the stainless- steel bottom. The water so there is steam, your glasses fog up, and the rot slithers down drain. The shells cluster in cracked bits and are removed by hand. Finally, now somewhere closer to one a.m., the case bottom clean, even gleaming, and the team goes back to the giant machine along the north wall to return with heaping shovels of virginal white snow. Clean ice, the cleanest you’ve ever seen after and they pile it in heaps into the case, building back the buffer between the wet semi- rot that will be the bottom of the case and a top retail surface downy and clean. When they are finished, the ice sparkles. No more skate rink, each chip separate and glittering in the light; the perfect platform to sell good fish. The smell, once choking, is not just muffled but nonexistent. A very real and solid barrier has been erected. And once the floor has been sprayed down and mopped across with a giant squeegee, the entire scene will feel like a dream. Tomorrow morning the fish will be laid down again in their metal trays, cut parsley and trills of red peppers arranged on top. And it won’t be unhygienic in the least. It will be undetectable and irrelevant. There will be a thick wall of ice separating the retail surface from the depths below. And in this way—the very real way the fish case at Whole Foods on the Bowery can be simultaneously appalling and perfectly hygienic and safe—it is a fitting metaphor for the grocery business as whole.

***

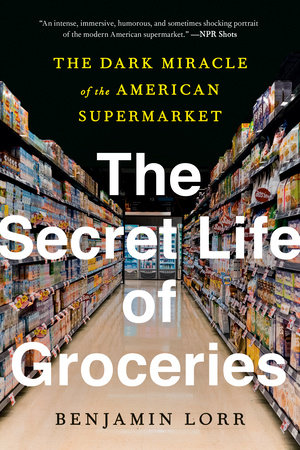

This book is about the grocery store. About the people who work there and the routes of supply that define it. It is the product of five years of research, hundreds of interviews, and thousands of hours tracking down and working alongside the buyers, brokers, marketers, and managers whose lives and choices define our diet. The five years were a time of dramatic upheaval. Walmart seized organics. Amazon seized Whole Foods. The promise of automation loomed over trucking. Minimum wage laws shifted, giving employees the promise of a new salary floor. Yet, what I found, whether talking to Whole Foods executives about the Amazon deal or to new Amazon employees as they stocked shelves, was that during this upheaval the most primal drives in the industry weren’t so much disrupted as elevated and laid bare.

What emerged is a fascinating and largely hidden world. In 2018, Americans spent $701 billion at supermarket- style grocery stores, still our largest food expenditure by a wide there are 38,000 of these stores across this land, and the average adult will spend 2 percent of their life inside one. They are the interface most familiar and least understood in our food system: bland to the point of invisibility, so routine they blur into background. And yet the grocery store exists as one of the only places where our daily decisions impact—make us complicit in—a system have come in equal parts to scorn and see as savior. We’ve been happy to let more impersonal aspects of our food system—from industrialized slaughterhouses to farm bill subsidies—take up the share of investigation and critique. But to understand how and why our food gets to us in the form it does, the grocery store is a powerful entry point. It is not only the way that most of us are introduced to the system, tagging along with Mom as she shops, it is perhaps the best opportunity to understand the system on the terms of the people who operate it on our behalf.

***

In the retail store, the deboned bulk chilled chicken breasts, or Granny Smith apples, or long fillets of frozen salmon, or whatever other food you want to imagine—arrive in their cardboard boxes, vacu-sealed in a marvel of plastic packaging, and when you click your box cutter down and reach to take them out, they cease being food. Another transformation has occurred; they are product now. Merchandise. SKUs. Listen to the retail managers and assistant managers talk among themselves: the word “food” doesn’t come up; it is an irrelevant, unhelpful, even illogical way to discuss the work of a grocery. To these men it is always product. And so, an item within the grocery matrix loses its identity as food and becomes product. It is liberated; its transformation is no less critical to the project of civilization. Now it is defined by the cubic inches of its packaging, its price per unit, and the velocity of its sales. It is not until much later, the moment the customer comes pushing their cart down the aisle and reaches out for that Styrofoam tray, that our chicken becomes food again. It is a tenuous thing, but suddenly it has a new owner and a new meaning; now it will be eaten, and everything that matters about it has changed to reflect that fact.

And when you start digging into precisely how the people in grocery think, you find one thing open and waiting in the center: the maw. That voracious, devouring hole we feed three to thirty times a day, swallowing and salivating and stuffing, ceaseless in its demands right up to the point we lie in a hospital bed and it gets temporarily assisted by a polyurethane tube. The maw to me, like the sun above interfacing with the chloroplasts below the leaf, is more than just a mouth: it is a secular revelation, a complex of destruction and creativity, anchored in need. It is the sensory cells of the gut. The neuronal charge to acquire. The curiosities, comforts, and cravings we convince ourselves are necessities. It—like the Vedic concept of Self/ self—comes in the universal as well as the personal, each of our unique pie holes mere tributaries to some more tremendous vortex right at the heart of the human project. And it is this maw more than anything that animates the wonks in the grocery back room, poring over their spreadsheets, deciding how to stock our shelves. More than greed, health, altruism, grocery wants to serve. The fact that we make serving that need so complicated, the fact that it ends in the contradiction that is the Whole Foods fish counter, beautiful and vile at the same time, should not be an invitation to scorn the system—or ourselves— but an opportunity for introspection and perhaps even growth. And ultimately it should upend our perception of grocery to remember it isn’t about food, it never has about food— food is the business of eating— grocery, we’ll see, completely different; it’s the business of desire.

Copyright © 2020 by Benjamin Lorr. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.