1

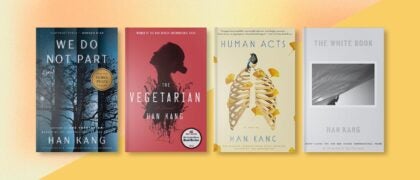

The Vegetarian

Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way. To be frank, the first time I met her I wasn’t even attracted to her. Middling height; bobbed hair neither long nor short; jaundiced, sickly-looking skin; somewhat prominent cheekbones; her timid, sallow aspect told me all I needed to know. As she came up to the table where I was waiting, I couldn’t help but notice her shoes—the plainest black shoes imaginable. And that walk of hers—neither fast nor slow, striding nor mincing.

However, if there wasn’t any special attraction, nor did any particular drawbacks present themselves, and therefore there was no reason for the two of us not to get married. The passive personality of this woman in whom I could detect neither freshness nor charm, or anything especially refined, suited me down to the ground. There was no need to affect intellectual leanings in order to win her over, or to worry that she might be comparing me to the preening men who pose in fashion catalogues, and she didn’t get worked up if I happened to be late for one of our meetings. The paunch that started appearing in my mid-twenties, my skinny legs and forearms that steadfastly refused to bulk up in spite of my best efforts, the inferiority complex I used to have about the size of my penis—I could rest assured that I wouldn’t have to fret about such things on her account.

I’ve always inclined towards the middle course in life. At school I chose to boss around those who were two or three years my junior, and with whom I could act the ringleader, rather than take my chances with those my own age, and later I chose which college to apply to based on my chances of obtaining a scholarship large enough for my needs. Ultimately, I settled for a job where I would be provided with a decent monthly salary in return for diligently carrying out my allotted tasks, at a company whose small size meant they would value my unremarkable skills. And so it was only natural that I would marry the most run-of-the-mill woman in the world. As for women who were pretty, intelligent, strikingly sensual, the daughters of rich families—they would only ever have served to disrupt my carefully ordered existence.

In keeping with my expectations, she made for a completely ordinary wife who went about things without any distasteful frivolousness. Every morning she got up at six a.m. to prepare rice and soup, and usually a bit of fish. From adolescence she’d contributed to her family’s income through the odd bit of part-time work. She ended up with a job as an assistant instructor at the computer graphics college she’d attended for a year, and was subcontracted by a manhwa publisher to work on the words for their speech bubbles, which she could do from home.

She was a woman of few words. It was rare for her to demand anything of me, and however late I was in getting home she never took it upon herself to kick up a fuss. Even when our days off happened to coincide, it wouldn’t occur to her to suggest we go out somewhere together. While I idled the afternoon away, TV remote in hand, she would shut herself up in her room. More than likely she would spend the time reading, which was practically her only hobby. For some unfathomable reason, reading was something she was able to really immerse herself in—reading books that looked so dull I couldn’t even bring myself to so much as take a look inside the covers. Only at mealtimes would she open the door and silently emerge to prepare the food. To be sure, that kind of wife, and that kind of lifestyle, did mean that I was unlikely to find my days particularly stimulating. On the other hand, if I’d had one of those wives whose phones ring on and off all day long with calls from friends or co-workers, or whose nagging periodically leads to screaming rows with their husbands, I would have been grateful when she finally wore herself out.

The only respect in which my wife was at all unusual was that she didn’t like wearing a bra. When I was a young man barely out of adolescence, and my wife and I were dating, I happened to put my hand on her back only to find that I couldn’t feel a bra strap under her sweater, and when I realized what this meant I became quite aroused. In order to judge whether she might possibly have been trying to tell me something, I spent a minute or two looking at her through new eyes, studying her attitude. The outcome of my studies was that she wasn’t, in fact, trying to send any kind of signal. So if not, was it laziness, or just a sheer lack of concern? I couldn’t get my head round it. It wasn’t even as though she had shapely breasts which might suit the ‘no-bra look’. I would have preferred her to go around wearing one that was thickly padded, so that I could save face in front of my acquaintances.

Even in the summer, when I managed to persuade her to wear one for a while, she’d have it unhooked barely a minute after leaving the house. The undone hook would be clearly visible under her thin, light-coloured tops, but she wasn’t remotely concerned. I tried reproaching her, lecturing her to layer up with a vest instead of a bra in that sultry heat. She tried to justify herself by saying that she couldn’t stand wearing a bra because of the way it squeezed her breasts, and that I’d never worn one myself so I couldn’t understand how constricting it felt. Nevertheless, considering I knew for a fact that there were plenty of other women who, unlike her, didn’t have anything particularly against bras, I began to have doubts about this hypersensitivity of hers.

In all other respects, the course of our our married life ran smoothly. We were approaching the five-year mark, and since we were never madly in love to begin with we were able to avoid falling into that stage of weariness and boredom that can otherwise turn married life into a trial. The only thing was, because we’d decided to put off trying for children until we’d managed to secure a place of our own, which had only happened last autumn, I sometimes wondered whether I would ever get to hear the reassuring sound of a child gurgling ‘dada’, and meaning me. Until a certain day last February, when I came across my wife standing in the kitchen at day-break in just her nightclothes, I had never considered the possibility that our life together might undergo such an appalling change.

*

‘What are you doing standing there?’

I’d been about to switch on the bathroom light when I was brought up short. It was around four in the morning, and I’d woken up with a raging thirst from the bottle and a half of soju I’d had with dinner, which also meant I was taking longer to come to my senses than usual.

‘Hello? I asked what you’re doing?’

It was cold enough as it was, but the sight of my wife was even more chilling. Any lingering alcohol-induced drowsiness swiftly passed. She was standing, motionless, in front of the fridge. Her face was submerged in the darkness so I couldn’t make out her expression, but the potential options all filled me with fear. Her thick, naturally black hair was fluffed up, dishevelled, and she was wearing her usual white ankle-length nightdress.

On such a night, my wife would ordinarily have hurriedly slipped on a cardigan and searched for her towelling slippers. How long might she have been standing there like that—barefoot, in thin summer nightwear, ramrod straight as though perfectly oblivious to my repeated interrogation? Her face was turned away from me, and she was standing there so unnaturally still it was almost as if she were some kind of ghost, silently standing its ground.

What was going on? If she couldn’t hear me then perhaps that meant she was sleepwalking.

I went towards her, craning my neck to try and get a look at her face.

‘Why are you standing there like that? What’s going on . . .’

When I put my hand on her shoulder I was surprised by her complete lack of reaction. I had no doubt that I was in my right mind and all this was really happening; I had been fully conscious of everything I had done since emerging from the living room, asking her what she was doing, and moving towards her. She was the one standing there completely unresponsive, as though lost in her own world. It was like those rare occasions when, absorbed in a late-night TV drama, she’d failed to notice me arriving home. But what could there be to absorb her attention in the pale gleam of the fridge’s white door, in the pitch-black kitchen at four in the morning?

‘Hey!’

Her profile swam towards me out of the darkness. I took in her eyes, bright but not feverish, as her lips slowly parted.

‘. . . I had a dream.’

Her voice was surprisingly clear.

‘A dream? What the hell are you talking about? Do you know what time it is?’

She turned so that her body was facing me, then slowly walked off through the open door into the living room. As she entered the room she stretched out her foot and calmly pushed the door to. I was left alone in the dark kitchen, looking helplessly on as her retreating figure was swallowed up through the door.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.