Chapter 1

Two days after his father’s funeral, a distraught Gaston Driant came to the

mairie of St. Denis, asking to see Bruno Courrèges, the town’s chief of police. Bruno assumed that Gaston, a long-time acquaintance from the town tennis club, was still in shock at the dreadful nature of his father’s death. The old man, a widower, had been alone on his remote farm when he had suffered a fatal heart attack. He had not been found for several days. Patrice, the postman, liked to visit his older customers from time to time to see how they were, and he’d always found a friendly welcome at Driant’s home along with a glass of his homemade

gnôle, a notorious firewater that Bruno had learned to treat with great respect. When Patrice’s knock went unanswered, he had opened the kitchen door. Two cats had darted out, and then Patrice had reeled back from the smell. Then he had thrown up when he saw what the cats, desperate for food, had done to the dead farmer. When he recovered, he’d called Dr. Gelletreau, who he knew had been Driant’s physician, and waited outside in the fresh air for his arrival.

Gelletreau had come within the hour, accompanied by an ambulance. Once he had seen the body, he wrote a prescription for sleeping pills for Patrice, along with an instruction for the post office to grant him three days’ leave. Given the circumstances, Gelletreau’s death certificate, citing a heart attack as the cause of Driant’s demise, had understandably gone unquestioned. And as the doctor later told Bruno, he had been treating Driant for heart trouble for the past several months and the previous month had written an authorization for a pacemaker to be installed in Driant’s chest.

Bruno was surprised when Gaston firmly refused his offer to take him down for coffee to Café Cauet, saying, “This is going to be official, Bruno, so we’d better stay here in your office. I just came from a new

notaire in Périgueux for what I understood to be the reading of Dad’s will. He’d sent a letter for me that was waiting at the funeral parlor. My sister, Claudette, was with me; she came down from Paris. We were stunned by what the

notaire told us. Anyway, on the drive back here, we agreed I should come and see you as an old friend. I mean, you know the law, and we don’t.”

There was nothing left of his father’s estate, Gaston explained. Without telling his children, Driant had sold the farm and put all the money into an insurance policy that would pay for him to spend the rest of his days in an expensive residential home for the elderly. He was due to go there in September. The

notaire said that Driant had insisted on spending one last summer on the farm he’d inherited from his father.

“Claudette and I can’t believe that Dad didn’t tell us what he planned to do,” Gaston went on. “And we don’t understand why he went to this fancy

notaire in Périgueux when the whole family had always used Brosseil for wills and anything official. I was going to see Brosseil right after going to sit with Dad in the funeral parlor, but that was when I found the letter from the

notaire in Périgueux.”

Bruno nodded in understanding. Brosseil had followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather as the local

notaire in St. Denis. He knew everybody in the district and everybody had always used him for wills, property sales and official paperwork. Brosseil was something of a character, fussy and prim in dress and manner and exhibiting a vanity that was so ridiculous that it was almost endearing, a private joke that the whole town enjoyed. But Bruno knew that his work was meticulous and that he was as honest as the day was long.

“And this retirement home is not like Dad at all,” Gaston went on. “My sister looked it up on her phone. It’s an old château that was turned into a hotel, and now it’s a very grand home for the elderly. The fees start at four thousand euros a month. That’s more than double what I earn. And because my dad’s dead, this home gets to keep all the insurance money. It all seems very fishy to Claudette and me, and we agreed that I’d ask you about it.”

Bruno took down the names and addresses of the

notaire, the insurance agent and the residential home and made a photocopy of the

notaire’s letter to Gaston.

“Let me look into this,” he said. “How old was your dad?”

“Seventy-four next birthday, in November. But apart from what Gelletreau said about his heart, he seemed in good shape when I saw him last, still kept up the farm. I came up here in March as usual to help him with the lambing. And that’s another thing: What’s going to happen to the sheep and ducks and chickens?”

After being laid off when the local sawmill had closed a couple of years earlier, Gaston had found a job in Bordeaux as an ambulance driver. Bruno had written him a reference, citing Gaston’s clean driving record and his years as a volunteer fireman, which had brought him some qualifications in first aid. Gaston was raising two daughters who were still in secondary school, so he’d probably been hoping for a decent inheritance when his father died.

“He’d never mentioned these plans to you or Claudette?” Bruno asked.

Gaston shook his head. “When we were talking over dinner at lambing time, he said he wanted to stay on the farm as long as he could and then go to the retirement home here in St. Denis where he knew everybody. I can’t understand what got into him.”

“Leave it with me,” Bruno said. “I’ve got your address and phone number, so I’ll let you know what I find out. All I can say at this stage is that usually in cases of elderly people changing their wills there has to be a formal declaration signed by a doctor and a lawyer that establishes the change is being made freely and of their own volition and that they’re in full possession of their faculties. If there is no such declaration, you might have a case. But going up against a

notaire and an insurance firm would probably be a very lengthy and expensive affair.”

“Merde.” Gaston grunted. “It’s always the same. One law for the rich and another for the rest of us.”

“In this instance, Gaston, if there is no such attestation, the law could be on your side. And you know the mayor and I will back you. Again, my condolences on your loss. I liked your dad. He was always a regular at the rugby games and at the hunting club dinners. And that

gnôle he made was the best

eau-de-vie in the valley, even if it wasn’t really legal. I hope at least he left you a few bottles.”

“One or two, but he drank most of that rocket fuel himself, and I can’t say I blame him,” Gaston said, rising to shake Bruno’s hand.

Bruno’s first stop was just down the hall at the registry. There he consulted the commune’s cadastre, the detailed map showing each property lot, its owner and the tax data. The new ownership had not yet been registered. Driant’s farm was listed as sixty-two hectares, which would be big for a vineyard but was small for a sheep farm, mostly woodland and poor pasture up on the plateau. What surprised Bruno was that Driant had made an application for a construction permit to build four new houses on his land. He had described them in the application as cottages for farmworkers, which was what such applications usually said even when the real intention was to sell them off as vacation homes.

Bruno had never heard of Monsieur Sarrail, the

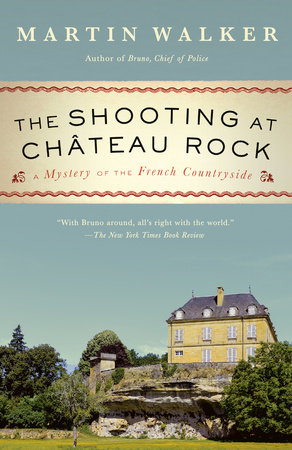

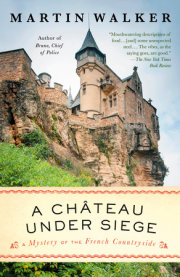

notaire in Périgueux, but from the letterhead he knew he was in a fancy location on the rue du Président Wilson in the center of the city. When he looked up the agent for the insurance company, Bruno found that he had an address in the same building. That was interesting. He checked the website of the retirement home and was startled to see a handsome château near Sarlat that he recognized. He’d been invited to dinner there one evening by his friend the baron some five or six years ago, when it had been a newly restored four-star hotel with a dining room that was said to be aiming for a Michelin rosette. The meal had been a touch too nouvelle cuisine for Bruno’s taste, the portions small and the plates overdecorated in an effort to appear artistic and inventive. Bruno and the baron had thought it pretentious. They’d never been back.

As a retirement home, it offered what were described as full medical services, a registered nurse, a physiotherapist, a masseuse on the premises and a resident doctor who also sat on the management board. It advertised itself as a “luxury establishment for the discerning customer, modeled on an exclusive private club.” It boasted its own movie theater, a spa, a nine-hole golf course and a manager who had previously been on the staff of the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris.

The chef was said to have served his apprenticeship at a restaurant in Geneva that Bruno had heard of, and had then been a sous-chef at the Relais Louis XIII in Paris. Bruno had been taken there for dinner one evening by his old flame Isabelle and had eaten the finest quenelles of his life. Why on earth would Driant want to go to a grand retirement home like that, where the old sheep farmer would be sneered at by the other inhabitants and probably also by the staff? Subscriptions by application, the website said.

Bruno found the manager’s name on the website, called the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris and asked for the head of security. He introduced himself and found that he was speaking to a former detective of the Préfecture de Police of Paris, who had heard of Bruno from their mutual friend J-J, the chief detective for the

département of the Dordogne. Bruno said he was checking on a luxury retirement home in his region that claimed the manager had worked at the Crillon. The old detective laughed at the name. The man in question had indeed worked there for a few months as one of several junior assistant concierges, whose main duty was to take care of the guests’ baggage and to collect and deliver their laundry and dry cleaning. He had been competent, the detective said, but had been asked to leave after one affronted female guest complained that he had offered his services as a gigolo.

Bruno then phoned J-J at police headquarters in Périgueux to ask if he knew anything about the

notaire or the retirement home, and whether this sounded like some kind of insurance scam.

“I haven’t heard about the retirement home, but this is something new in the

notaire system,” said J-J. “He’s the first one here, but there are several in Paris, a

notaire who forms a partnership with an insurance agent, an accountant and an investment adviser to offer full financial consultancy, usually for rich people. They call it wealth management. So far I’ve heard nothing bad about the guy in Périgueux, but it’s not really my field. I can have a discreet word with a colleague from the

fisc if you like.”

Bruno felt reassured. The

fisc was the slang term for the Brigade Nationale de la Répression de la Délinquance Fiscale. Although they sometimes worked closely with the police, they were not police officers, since they applied the fiscal code and reported to the Ministry for the Budget and Public Finances, not to the Ministry of the Interior. Bruno passed along what he’d heard about the manager of the retirement home from J-J’s friend at the Crillon, which left him laughing.

Bruno then went to ask Claire, the secretary at the

mairie, if the mayor was free. The mayor must have heard him, since he called through the half-open door to tell Bruno to come right in. Bruno explained what he’d heard and asked if the mayor knew anything about Driant applying for a construction permit.

“Yes, and he got it approved by the council,” the mayor said. “It was a matter of professional courtesy. Driant served two terms on the council for the commune, before your time, Bruno. You know how councillors tend to support one another’s projects, and with all these retirees coming here from the rest of France and Europe we’re getting a housing shortage. But I agree it sounds odd. I’ll find out what my colleague in Sarlat knows about this retirement home. It doesn’t sound at all like the kind of place Driant would have enjoyed.”

“You know Driant’s farm,” Bruno said. “What do you think it would be worth?”

“They’d never sell it these days for raising sheep, not since Brussels cut the hill farm subsidies. Driant had one of the last of them,” the mayor replied. “The house and barns alone might fetch a hundred and fifty thousand, but only if somebody wanted to make it into a small hotel and

gîtes. I assume that’s what the construction permit was for. It would depend on how much repair work would be needed. But the place has a great view. It could be popular in summer with the right management. Maybe you should talk to Brosseil, then find out whether Driant had sworn a statement of competence, and we’ll talk again.”

Copyright © 2020 by Martin Walker. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.