1

May 19, 1950

Hotel Astor: Arrival

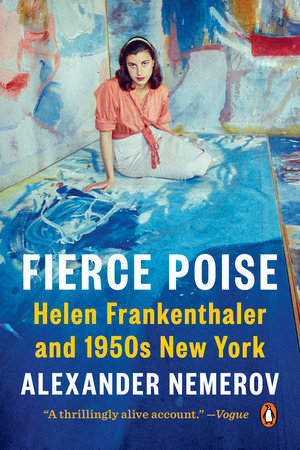

She walked into the lobby of the Hotel Astor dressed as Picasso's Girl before a Mirror. Her costume was outlandish, like a Technicolor cartoon: a dyed mop on her head for yellow hair, pajamas for the feeling of the boudoir, a painted curtain wrap for a backdrop, a mirror in her left hand. Two nippled balloons floated on her arm and hip, displaced breasts set at crazy angles. By her side was Gaby Rodgers, her friend and roommate, impersonating a cover girl: sporting a blouse of black-and-white diamonds, as retiring as a racing flag, a red-dyed mop on her head, and the current issue of Flair, a new fashion magazine. The two young women, both fresh out of college, walked through the lobby to the elevator and took it to the ninth floor.

The door opened to reveal a vast ballroom, the largest in America. A din of alcohol-fueled conversation rose to the rafters. More than a thousand partygoers were celebrating Spring Fantasia, an artists' benefit costume ball. Large cut-out mobiles hung from the ceiling, depicting schools of fish, a sunflower, a vast bird on a branch, a bodybuilder, the moon. A couple of revelers wore Vesalian anatomical suits showing nerves, blood vessels, and striated muscles. A man walked around dressed as a spider, complete with a fifteen-foot web and large fly. A trio wearing black and white called themselves "the Death of Color." A husband and wife, the makers of Christmas card art, dressed as Parisian pimp-and-prostitute "Apache Dancers." One reveler sported only a fig leaf, and another, calling himself "the Rain Maker," wore long strings of buttons that clacked together as he danced.

Helen and Rodgers joined the exultation, at home among the partyers, having fun. But they were also on a mission, keen to create names for themselves. Rodgers was intent on becoming a serious actress; Helen had her own plans. The ball was a benefit for the Artists Equity Association, an organization devoted to establishing rights for all artists. Its president, sixty-year-old painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, in attendance that night, worked hard to achieve this noble goal. But Helen and her friend did not have their minds on equity. What if there were good artists and bad artists and, yes, great artists? What if it all was not fair and what if fairness was for losers? Then there was no equity, only a hierarchy based on ambition and talent and luck. A few people succeeded. Most failed.

The same with celebrity. The ceremonial emcee that night was Gypsy Rose Lee, thirty-nine, the famous stripper and author, who at that stage of her career had been performing striptease shows for a touring carnival-earning a vast income-and hosting two shows on the intriguing new medium of television. No doubt it was a thrill to catch a glimpse of her. With her sparkling gown and crazed tiara-a swirl of hanging stars protruding from her head like a rack of celestial antlers-she cut a figure at the ball. Rodgers's rose-filled cover of Flair-a magazine that Lee had written for-maybe caught the star's attention.

But Helen and Rodgers aimed to be well-known themselves, unfazed by the older artists and entertainers who had seen so much more of the world than they. When Life magazine ran a feature on the Astor ball some three weeks later, the two unknown young women merited the only color photograph. Their outfits and personae drew attention, muscling some of the more earnest but less flashy costumes out of the limelight. It was a way of becoming public, of filling the stage-a contrast to how insecure they both really were. Two photographs taken at their lower Manhattan apartment a few hours earlier show them looking sweet and sedate, like adolescent girls before a night of trick or treating, with Helen standing above her friend, who sits in a butterfly chair. At the ball, however, the two young women grew larger than life, knowing well enough how to be a party's center of attention. The Life photographer pictures them from below, giving each a special stature. Magically, they assume the publication's house-style sexuality: pretty, white, wholesome, dishy, maybe available. Helen looks long and coltish. The irony of Rodgers holding a copy of a national magazine as she appears in a photograph for another national magazine turns out to be no irony at all. The cover girl and her cover girl friend knew how to draw interest.

Who cared if they had barely accomplished a thing by that night in May 1950?

It had been only the previous summer that Helen had graduated from Bennington College in southern Vermont. The school, founded in 1932 as a small all-women liberal arts college, was perfect for ÒFrankie,Ó as her friends called her. It was known for encouraging independent thought and spirited comradeship among the students, many of them precociously bright, fiercely introverted, and socially daring at the same time.

Helen came there as both a confident and a wounded person. She was born on December 12, 1928, the youngest of three daughters of New York State Supreme Court justice Alfred Frankenthaler and his wife, Martha. Alfred's star ascended during Helen's girlhood; having worked for more than two decades in private practice after receiving his law degree with honors from Columbia in 1903, he was elected to the state supreme court in 1926. There he won wide praise for his rulings on what had been his expertise in private practice: litigation stemming from defaults on mortgage bond payments. A Democrat, Alfred was celebrated during the Depression for a series of unprecedented legal decisions that allowed investors to recover losses from failed title and mortgage companies. Martha, fourteen years younger than her husband, like him came from a German Jewish family. Alfred's father, Louis, had immigrated from Untereisenheim to New York in the 1850s, starting as a dry goods merchant before opening a ribbon business. Alfred was born in New York City in 1881. Martha Lowenstein, born in Igstadt, in 1895, had immigrated to Manhattan with her family two years later. The couple married in December 1921, with Martha already pregnant. Seven months after the wedding she gave birth to Marjorie. Fourteen months later came Gloria. Helen arrived five years later.

A photograph taken in Atlantic City around 1933 shows the five Frankenthalers, close-knit, beaming for their picture. Martha is at the top, one arm around Gloria, the other on her husband's shoulder. Marjorie, the eldest, kneels in the front. Alfred, in his tank-top bathing suit, balances little Helen on his knee as she grips his hand with her tiny fingers. At home, the family was just as spirited and close, and Helen had a place at the dinner table from the time she was two years old. Sometimes they would go to Alfred's favorite restaurant, Dinty Moore's, on West Forty-sixth Street, where the proprietor, Jim "Dinty" Moore, was a good friend of Mr. Frankenthaler. It was a rare treat for Alfred, who worked hard, getting up at dawn and often staying late at the office. He would work during summer recesses of his court and it was said he rarely took a vacation. In his brilliance and dedication he could be disheveled, distracted. A story in the family is that on one icy winter day in the 1930s he slipped on the courthouse steps and fell to the sidewalk, where the only feature that distinguished him from the bums was his justice's robe.

Helen was Alfred's pride and joy. He marveled at her bright spirit, her curiosity and sense of adventure. Everything she did was wondrous. When she was a toddler and learning how to use the toilet, Helen finally succeeded on an evening when her parents were having a dinner party at the family's posh apartment. Coming into the dining room, she told her father proudly of her accomplishment. Just as proudly, he went to see, then insisted that the guests see, too. For Alfred, and for Martha, too, everything Helen made was a work of art. When she got some modest recognition-winning one of several honorable mention prizes in a Saks Fifth Avenue drawing contest when she was nine-they saved the newspaper announcement. Meanwhile her less conventional artistic intelligence was emerging. In her bathroom when she was little, Helen would fill the tiny sink with cold water and dispense droplets of her mother's bloodred nail polish into the basin, watching the patterns spread before draining the water and studying the stains on the white porcelain. Only the maid's screams would disrupt her reverie. Outside, when it was time for her and her nanny to walk back from the playground behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the family's apartment eight blocks away, Helen would insist on drawing a continuous chalk line as they slowly walked the route. Pedestrians moved out of the way, giving ground to the little girl of such singular concentration. Sometimes as Alfred and Martha walked down the street on family strolls, their three daughters walking ahead of them, Helen would overhear her father's praise. "Watch that child," Alfred used to say to his wife. "She is fantastic."

In October 1939, not long before Helen's eleventh birthday, Alfred underwent an operation for gallstones at Mount Sinai Hospital. He spent the next several months convalescing at home but then suddenly became ill and died on January 7, 1940, at age fifty-eight. The pallbearers at his funeral included New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, New York governor Herbert Lehman, and Judge Felix Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court. He left an estate valued at more than $900,000 to his wife and their three daughters.

The financial security hardly made matters better. For the next several years Helen went into a tailspin. She began to suffer migraine headaches. She convinced herself that she had a brain tumor. Panicking at school, she hesitated between asking to see a doctor and being afraid to do so. At Horace Mann and then at Brearley School in Manhattan, where she transferred in ninth grade, she spent hours in class ignoring the teacher while she tested her side vision, noting and fearing a wrinkly pattern she saw there-a pattern caused by the strain of her constant self-imposed vision tests. At home, when a migraine came on, she would "look at a chair, know it was a chair, know it had a word, know it was a word I used all the time, and would through some garbled way say to my mother to give me the name of what that thing was." When her mother would go to the grocery store, Helen trembled and cried, afraid she would never come back, and when her mother returned, Helen was scared to confide her fears and said nothing. She was gangly and awkward, her mouth full of braces. She did not emerge from this debilitating period until she transferred to Dalton, where a sympathetic headmistress mentored her. But the doubt and worry left their mark and never really went away.

At Dalton, Helen began to paint seriously. She excelled in the classes of Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican ŽmigrŽ painter of brightly colored cubist- and surrealist-inspired pictures. For Helen, the colors and fantasies of the man's paintings were not an escape and not a compensation. They offered instead some other reality in which she could get a fix on her own existence, these fields of blue and orange and ocher, with their singers and dancers and baying dogs. Tamayo gave Helen her first proper art training, teaching her how to mix varnish, turpentine, linseed oil, and tube pigments. He emboldened her to try big pictures-such as a life-sized portrait of the Frankenthalers' maid. She emerged as the teacher's favorite, though she resented it when Tamayo corrected her pictures.

Going to Bennington was a natural choice. Marjorie, a gifted writer, had gone to Vassar to study journalism. Gloria went to Mount Holyoke, receiving a respectable education of the kind then deemed sufficient and uncontroversial for a young woman. Bennington was something different. "Those Bennington girls," Martha Frankenthaler had said, fretting about her youngest daughter's choice of a school. "They do wild things, they bring Greenwich Village into the house, they write things you can't understand." Martha was proud, but she also worried that people would think that Helen hated her family, or that she was sleeping with someone, or that she traveled with Communists, or all of these things. But Helen was set on her choice. A photograph of her taken during her Bennington years shows her standing and smiling, elegant in her fashionable trousers and camel-hair coat, loafers, and white socks. Behind her is the Commons Building, where up in the third-floor studio she spent days and nights at her easel.

Paul Feeley, Helen's art professor, taught her how to make paintings in the style of Picasso. As open and encouraging as Tamayo, he would tack color illustrations of modern and Old Master paintings on the studio bulletin board and invite the students to critique each work. Helen did not hesitate to talk. Her new best friend, Sonya Rudikoff, was equally sharp, equally opinionated. It did not matter that they were just starting out and that the artists they spoke of, almost all of them men, had already traveled the route from recognition to fame to would-be immortality, their pictures memorialized in the pages of ARTnews and Art International. Evaluating their art inch by inch, Helen and Rudikoff did not shy from pointing out where it succeeded and where it failed. At the same time, Helen, like Rudikoff, felt herself part of a lineage established by these men, an artistic family at least as strong as her own. When Feeley stood at the students' backs, he did not mark on their pictures as Tamayo had done but would remark approvingly on their stylistic forebears: "Matisse is your daddy," he would say. "Picasso is your daddy."

At Bennington, the study and practice of modern painting was a part of the college's intensity, not an escape from it. Absorbing Feeley's teaching, looking around her, feeling a growing conviction in herself, Helen felt that art was more than a polite skill, a bit of polish and refinement, more than recipe making or getting married or a way to pass the time. She or any one of her close college friends would have argued that point with unseemly directness. Art at Bennington was nothing less than a transformative-even a religious-enterprise. It made life, shaped it, in the sense that you never truly saw a stream of mist curling over a green hill until you had thought about how you would paint it. The campus was politically active, primarily in the name of liberal candidates and causes-the commencement speaker at Helen's graduation in July 1949 was Democratic senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota-but the practice of art was a politics unto itself.

Copyright © 2021 by Alexander Nemerov. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.