Dear Reader,

Three days after the 2016 election, I sat at my writing desk overwhelmed by grief. I was not alone. Like many people (like you, perhaps), I’d had trouble sleeping and had already engaged in many conversations—with friends and family, students and colleagues, in person and on social media—about the spike in hate crimes, the pain and outrage, the devastation to come.

In my grief, I thought about many things. I thought about all the hard-won civil rights gains of the past fifty years, now under a new level of threat. I thought about the many communities—including immigrants, people of color, gay and transgender people, women, Muslims, Jews, progressives from all walks of life—now bracing themselves (or ourselves, for I belong to some of those groups) for an era of increased vulnerability. I thought about climate change. The Supreme Court. Democracy. Other nations, affected, watching. The future near and far.

I thought about a friend’s daughter, age seven, Black, born in the USA, who said she was scared that Trump would make her family leave the country. And another friend’s son, age four, who has two mothers, just as my children do; he asked whether their family would be torn apart.

I thought about my son, who was born days after Obama was first inaugurated, and had therefore always lived in a nation in which someone like him—Black and multiracial, child of an immigrant—could be president. For months, my son had been talking about using his kung fu skills to defend his Mexican friends from Trump and his wall. On November 9, he did not want to get out of bed for school, because, he said, he refused to set foot in a nation where Trump was president. It was not an act of fear; it was a boycott.

I thought about my four-year-old daughter’s words about Trump, spoken out of the blue: “We’re not beautiful to him. Nobody told me that. It’s just a feeling I have.”

I also thought about my grandmother, a poet and activist in Uruguay who died during the dictatorship. Born in Argentina, exiled under President Juan Perón (who, it must be pointed out, was not a dictator but a democratically elected authoritarian), she found refuge in the calm little nation of Uruguay, only to later watch both her native and adopted countries fall prey to military coups and reigns of terror, imprisonment, disappearances, and torture. Her later, unpublished poems, found in her house after she died, speak to the depths of her sorrow. She never had the chance to see those dictatorships lift. I wondered how she’d managed to get through each day, to stay alive inside, to keep fighting in the face of repression, to keep the faith, to take the long view. And I wondered about hope. Had she been able to retain any hope? Could she ever have imagined that, years later, in 2010, two of the brutally tortured political prisoners of the Uruguayan dictatorship would rise up to become the beloved president and First Lady of the nation? That José Mujica and Lucía Topolansky would preside over an era of unprecedented renewal and progressive change? In the thick of the bleak times, how could she have imagined such a future? How could she have imagined that the seeds of a bright future lay right there in the horrific times themselves? If I could go back in time to reach her, what would I say, and what would she, reaching forward toward me where I sat at my writing desk, have to say to me?

I thought about you that morning, though I may not know you personally. I thought about the long journey ahead for you and for me and for all of us, and I wondered what we would do—what we could do, what we must do—to get through these times as intact as possible, keeping sight of the long view, striving to stay sane, awake, engaged, and steadfast in the face of backlash and threats to the communities and values and democracy we hold dear.

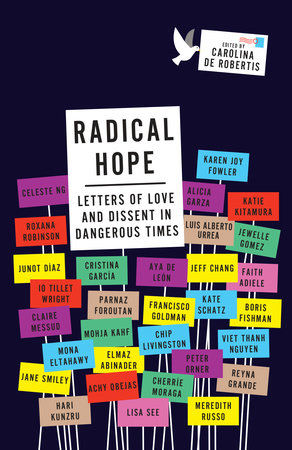

With all of that in mind, I started reaching out to writers to ask them to join me in what at first was a rather strange and nebulous concept: a collection of love letters in response to these political times.

Why love letters?

The epistolary essay, or essay in letter form, has unique powers. A potent example, one that inspired this book, lies in the great James Baldwin’s “My Dungeon Shook—Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Emancipation,” published in The Fire Next Time in 1963 (the same year Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., penned another seminal and brilliant epistolary essay, “Letter from Birmingham Jail”). Baldwin’s letter is addressed to his young nephew, and it gives voice to the injustices of institutional racism, the beauty and dignity of Black life, and the need for social change. The tone is at once tender and analytical, impassioned and nuanced, sweeping and deeply personal. Baldwin showed us that letter essays, as a form, are perfectly situated to blend incisive political thought with intimate reflections, folding them into a single embrace.

And that’s where the love comes in. Love is the blending agent that fuses the political and the intimate, providing urgency to one and context to the other. In a letter, the thoughts at hand are undergirded by the need to connect with the intended recipient—and this spirit of extension beyond oneself can link social themes to our personal spheres, to what cuts the closest and matters most. It is love that pushes us to face the journey toward justice without flinching, love that impels us to keep going on the long, hard road, love that provides the moral compass and the map.

As for the word dissent, it entered this project as an expression of how these letters defend truth in the face of repression. As my exiled grandmother could have told you, it doesn’t take a dictator to create an atmosphere of fear and shut down freedom of speech. All it takes is a bully at the helm, using threats and intimidation against any journalist (or former Miss Universe, or Hamilton actor, or ordinary citizen) to raise the specter of silence and censorship. And so, in such a climate, we can either silence ourselves and live in fear or we can stand ever taller and speak even louder. Dissent is verbal resistance. It is the affirmation of our voices, of our worth. It is, in a democracy, a fundamental right. And, in fact, dissent is not unrelated to love. They are complementary forces. In a climate where bigotry is an explicit value of those in institutional power, speaking love is an act of dissent.

The responses to my call for letters stunned me with their generosity, their depth, their keen insights, and their raw sense of urgency. I could not be more moved or humbled by the authors whose words are gathered here: They are leading novelists, journalists, poets, activists, and political thinkers. They are a collective mirror of precisely what makes this society strong and beautiful. They are members of diverse communities with roots all over the world—hailing from Syria, Lebanon, Mexico, Cuba, Nigeria, China, Japan, Egypt, India, Puerto Rico, Iran, Guatemala, indigenous North America, Russia, and various parts of Europe and Africa—and they all claim the United States as home. They are neighbors and activists, professors and artists, mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, straight and gay and transgender. They are Jews and Muslims, Christians and Buddhists, atheists and people undeclared in their spirituality. Above all, they are concerned citizens and community members who care deeply about their country and are compelled to offer their voices in the service of justice, courage, and radical hope.

Copyright © 2017 by Carolina De Robertis. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.