A House at the End of the World

| 2017 |First, the backstory, because, B. J. Miller has found, the backstory is unavoidable when you are missing three limbs.

Miller was a sophomore at Princeton when, one Monday night in November 1990, he and two friends went out for drinks and, at around 4:00 a.m., found themselves ambling toward a convenience store for sandwiches. They decided to climb a commuter train parked at the adjacent rail station, for fun. Miller scaled it first. When he got to the top, electrical current arced out of a piece of equipment into the watch on his wrist. Eleven thousand volts shot through his left arm and down his legs. When his friends reached him on the roof of the train, smoke was rising from his feet.

Miller remembers none of this. His memories don’t kick in until several days later, when he woke up in the burn unit of St. Barnabas Medical Center, in Livingston, New Jersey. Thinking he’d resurfaced from a terrible dream, he tried to shamble across his hospital room on the charred crusts of his legs until he used up the slack of his catheter tube and the device tore out of his body. Then, all the pain hit him at once.

Doctors took each leg just below the knee, one at a time. Then they turned to his arm, which triggered in Miller a deeper grief. (“Hands do stuff,” he explains. “Your foot is just a stinky, clunky little platform.”) For weeks, the hospital staff considered him close to death. But Miller, in a devastated haze, didn’t know that. He only worried about who he would be when he survived.

No visitors were allowed in his hospital room; the burn unit was a sterile environment. But on the morning Miller’s arm was going to be amputated, just below the elbow, a dozen friends and family members packed into a ten-foot-long corridor between the burn unit and the elevator, just to catch a glimpse of him as he was rolled to surgery. “They all dared to show up,” Miller remembers thinking. “They all dared to look at me. They were proving that I was lovable even when I couldn’t see it.” This reassured Miller, as did the example of his mother, Susan, a polio survivor who has used a wheelchair since Miller was a child: She had never seemed diminished. After the operation, when Miller was rolled through the hallway again, he opened his eyes as he passed her and said: “Mom, Mom. Now you and me have more in common.”

It wasn’t that Miller was suddenly enlightened; internally, he was in turmoil. But in retrospect, he credits himself with doing one thing right: He saw a good way to look at his situation and committed to faking that perspective, hoping that his genuine self might eventually catch up. Miller refused, for example, to let himself believe that his life was extra difficult now, only uniquely difficult, as all lives are. He resolved to think of his suffering as simply a “variation on a theme we all deal with: to be human is really hard,” he says. His life had never felt easy, even as a privileged, able-bodied suburban boy with two adoring parents, but he never felt entitled to any angst. He saw unhappiness as an illegitimate intrusion into the carefree reality he was supposed to inhabit. And don’t we all do that, he realized. Don’t we all treat suffering as a disruption to existence, instead of an inevitable part of it? He wondered what would happen if you could “reincorporate your version of reality, of normalcy, to accommodate suffering.” As a person with a disability, he was getting all kinds of signals that he was different and separated from everyone else. But he worked hard to see himself as merely sitting somewhere on a continuum between the man on his deathbed and the woman who misplaced her car keys, to let his accident heighten his connectedness to others, instead of isolating him. This was the only way, he thought, to keep from hating his injuries and, by extension, himself.

Miller returned to Princeton the following year. He had three prosthetics and rode around campus in a golf cart with a rambunctious service dog named Vermont who, in truth, was too much of a misfit to perform any concrete service. Miller had wanted to work in foreign relations, in China; now he started studying art history. He found it to be a good lens through which to keep making sense of his injuries.

First, there was the discipline’s implicit conviction that every work is shaped by the viewer’s perspective. He remembers looking at slides of ancient sculptures in a dark lecture hall, all of them missing arms or noses or ears, and suddenly recognizing them for what they were: fellow amputees. “We were, as a class, all calling these works monumental, beautiful, and important, but we’d never seen them whole,” he says. Time’s effect on these marble bodies—their suffering, really—was understood as part of the art. Medicine didn’t think about bodies this way, Miller realized. Embedded in words like “disability” and “rehabilitation” was a less generous view: “There was an aberrant moment in your life and, with some help, you could get back to what you were, or approximate it.” So, instead of regarding his injuries as something to get over, Miller tried to get into them, to see his new life as its own novel challenge, like traveling through a country whose language he didn’t speak.

This positivity was still mostly aspirational. Miller spent years repulsed by the “chopped meat” where his arm ended and crushed with shame when he noticed people wince or look away. But he slowly became more confident and playful. He replaced the sock-like covering many amputees wear over their arm stumps with an actual sock: first a plain sock, then stripes and argyles. Then, one day he forgot to put on any sock and—just like that—“I was done with it. I was no longer ashamed of my arm.” He became fascinated by architects who stripped the veneer off their buildings and let the strength of their construction shine through. And suddenly, the standard-issue foam covers he’d been wearing over his prosthetics seemed like a clunky charade—Potemkin legs. The exquisitely engineered artificial limbs they hid were actually pretty interesting, even sexy, made of the same carbon fiber used as a finish on expensive sports cars. Why not tear that stuff off and delight in what actually is? Miller recalled thinking. So he did.

For years Miller collected small, half-formed insights like these. Then he entered medical school and discovered palliative care, an approach to medicine rooted in similar ideas. He now talks about his recovery as a creative act, “a transformation,” and argues that all suffering offers the same opportunity, even at the end of life, which gradually became his professional focus. “Parts of me died early on,” he said recently. “And that’s something, one way or another, we can all say. I got to redesign my life around this fact, and I tell you it has been a liberation to realize you can always find a shock of beauty or meaning in what life you have left.”

One morning in July 2015, Miller took his seat at a regular meeting of palliative-care doctors at the University of California San Francisco’s cancer center. The head of the team, Dr. Michael Rabow, started with a poem. It was a tradition, he later told me, meant to remind everyone that this was a different sort of hour in their schedule, and that, as palliative-care physicians, they were seeking different varieties of outcomes for their patients: things like comfort, beauty, and meaning. The poem was called “Sinkhole,” and it seemed to offer some sneaky, syntactically muddled wisdom about letting go. When it was over, there was a beat of silence. (It was sort of a confusing poem.) Then Rabow encouraged everyone to talk about any patients who had died since their last meeting. Miller was the first to speak up.

Miller, now forty-five years old, with deep brown eyes and a scruffy, silver-threaded beard, saw patients one day a week at the hospital. He was also entering his fifth year as executive director of a small, pioneering hospice called the Zen Hospice Project, which originated as a kind of compassionate improvisation at the height of the AIDS crisis, when members of the San Francisco Zen Center began taking in sick, often stigmatized young men and doing what they could to help them die comfortably. The hospice is now an independent nonprofit group that trains volunteers for San Francisco’s Laguna Honda public hospital as well as for its own revered, small-scale residential operation. (Two of the facility’s six beds are reserved for UCSF, which sends patients there; the rest are funded through sliding-scale fees and private donations.) Once an outlier, Zen Hospice had come to embody a growing nationwide effort to reclaim the end of life as a human experience instead of primarily a medical one. The goal, as Miller likes to put it, is to “de-pathologize death.”

Around the table at UCSF, Miller stood out. The other doctors wore dress pants and pressed button-downs—physician-casual—while he wore a sky blue corduroy shirt with a tear in the sleeve and a pair of rumpled khakis; he could have come straight from camping or Bonnaroo. Even just sitting there, he transmitted a strange charisma—a magnetism which people kept telling me was hard to explain but also necessary to explain, since the rapport that Miller seems to instantly establish with everyone is a part of his gift as a clinician.

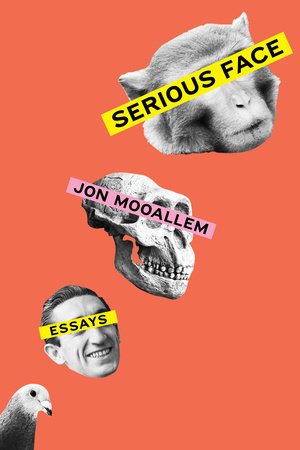

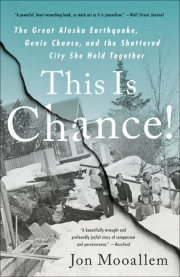

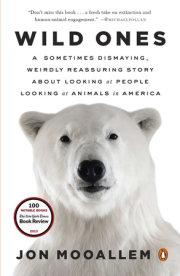

Copyright © 2022 by Jon Mooallem. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.