1“Everything Moves”The exposition

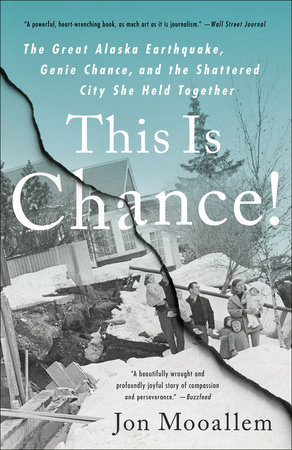

This book is called

This Is Chance! It was written by Jon Mooallem, published by Random House, edited by Andy Ward.

It tells the story of a single catastrophic weekend in a faraway town, and of the people who lived through it: ordinary women and men who—when the most powerful earthquake ever measured in North America struck, just before sundown on Good Friday, 1964—found themselves thrown into a jumbled and ruthlessly unpredictable world they did not recognize. They would spend the next few days figuring out, together, how to make a home in it again.

The name of the town is Anchorage, Alaska—a blotch of Western civilization in the middle of emptiness. In those days, the state of Alaska was still brand-new and often disregarded as a kind of free-floating addendum to the rest of America. But Anchorage was Alaska’s biggest and proudest city, a community whose “essential spirit,” one visitor wrote, “reached aggressively and greedily to grasp the future, impatient with any suggestion that such things take time.” It was a modern-day frontier town that imagined it was a metropolis, straining to make itself real.

That determination made it difficult for those living in Anchorage to recognize how indifferently the city they were building could be knocked down—to imagine that, early one Friday evening, the very ground beneath them might rear up and shake their town like “a dog shaking an animal he’s killed,” as one man later described it. Even while the earth was moving, the ferocious strangeness of what was happening to Anchorage was hard for people to internalize or accept. Buildings keeled off their foundations, slumped in on themselves, split in half, or sank. Four-foot-high ground waves rolled through the roads as though the pavement were liquid. A city of infallible right angles buckled and bent.

It wasn’t as though, before the quake, people in Anchorage pictured these things happening and dismissed them as impossible; they just never pictured them. They couldn’t. More to the point: Why would they? Like all of us, they looked around and registered what they saw as stable and permanent: a world that just was.

But there are moments when the world we take for granted instantaneously changes; when reality is abruptly upended and the unimaginable overwhelms real life. We don’t walk around thinking about that instability, but we know it’s always there: at random, and without warning, a kind of terrible magic can switch on and scramble our lives.

As

LIFE magazine would put it afterward, struggling to explain the hidden volatility that caused the quake, “Somewhere, the earth is quivering all the time.”

This first chapter of the book shows an afternoon in town one month before the disaster—by way of introduction. The date was Sunday, February 23, 1964; the time, just before one p.m.

All of Anchorage, it seemed, had gathered on Fourth Avenue for the last day of Fur Rendezvous, a week-long winter carnival that enveloped downtown. Fur Rendezvous was one of the longest-running traditions in a community that didn’t have many traditions yet, something for the burgeoning city to look forward to in the coldest, loneliest stretch of winter. Over the years, the exposition’s organizers had kept heaping on more activities and amusements until, by now, Fur Rendezvous had swelled into a kind of ramshackle Mardi Gras of the North. There were auctions, craft markets, concerts, carnival rides, pony rides, go-kart races, ski races, a beard-growing contest, and a homemade fur hat competition. There were beauty pageants and dances, and appearances by out-of-town celebrities like “television’s first flying cowboy,” the “King of Organ Sounds,” and a dog purported to be the actual Lassie, who had jetted into Anchorage in her own first-class seat. The Girl Scouts were selling cotton candy. The Boy Scouts were selling hot dogs. The Mormon Church was also selling hot dogs. And this year, Fur Rendezvous was proud to present its first-ever judo tournament.

That Sunday afternoon, everyone had come out for the races. The deciding heat of the World Championship Sled Dog Races was about to start, the finale of each year’s Fur Rendezvous week. Dog mushers would dart along a twenty-five-mile trail through the streets of Anchorage, then east into the foothills of the Chugach Mountains and back again—starting and finishing right here, on Fourth Avenue, in the heart of downtown.

After a week of excitement, the orderliness and decorum of the crowd was beginning to fray. Spectators spilled far beyond the bleachers set up on either side of the road. Kids clambered up a sprawling mountain ash tree to get a better view, moving rambunctiously, snapping off limbs. At one point, a chagrined city employee counted eighty adults standing on the roof of the log cabin in front of city hall. “They have estimated the crowd at twelve thousand people,” announced a debonair man named Ty Clark, covering the races for local radio station KENI. “Twelve thousand people!” Clark sounded astonished—but more than astonished, pleased. All afternoon, in fact, he would have an almost superstitious tic of emphasizing for listeners how very big this event in Anchorage was, and the formidable bigness of Anchorage in general. “This is the one time of year—the only time of the year,” he noted, “that we ever get that many people into the business district of Alaska’s largest city.”

KENI’s live coverage of the sled dog races had become its own big and freewheeling tradition, stretching far beyond what seemed possible for a small-market AM station in the middle of Alaska at the time. The station had virtually its entire staff—thirty-two people—working that Sunday and was broadcasting from nine different locations along the route, as well as from its helicopter, the KENI Kopter, circling overhead. They’d also deployed a couple of television cameras to simulcast on KENI-TV, Anchorage channel 4. And for the first time, KENI was relaying its coverage of the races to the small town of Cordova, 150 miles away. “It gets bigger and better every year!” Ty said.

Ty was anchoring the broadcast from the starting line on Fourth Avenue alongside his boss, Alvin O. Bramstedt, who had helped launch KENI in 1948, then taken over the station and aggressively built it up. KENI was now the flagship of Alaska’s largest radio network, Midnight Sun Broadcasters Incorporated, which included sister stations in Fairbanks, Ketchikan, and Juneau. Bramstedt, the network’s president and majority owner, had become one of Anchorage’s most prominent businessmen. Around town, everyone knew him as “Bram.”

He was a tall and polished-looking man, despite the rheumatoid arthritis that had been breaking down his body since his twenties. At forty-six, his hands were craggy and stiff. He hobbled instead of walked; his legs were like lumber. Still, he never complained. He seemed to move through the city in a vapor of his own cheerfulness and sincerity, verging on sappiness. His faith in Alaska’s future was unconditional; his love of America, and belief that it must beat back the threat of communism, was absolute. (Bram was convinced that at least one or two of his staff at KENI were Soviet spies; it wasn’t that anyone seemed particularly suspicious, but he took for granted that the Russians were infiltrating American media, and these were just the odds.) And though Bram reveled in competition—he paid his teenage son fifty cents to watch Anchorage’s only other television channel and make a list of every commercial, so that KENI might poach its advertisers—his main rival had also been the best man at his wedding and remained one of his closest friends.

Bram had always considered broadcasting more of a public service than a business. It was the cornerstone of any decent democracy, with a responsibility to educate the public and the capacity to bind a community together. KENI reflected those ideals. It was arguably the most successful of Anchorage’s five commercial radio stations and clearly the one most enmeshed with civic life. Its headquarters were a city landmark, housed inside the grand Fourth Avenue Theatre building in the center of downtown, with the KENI television tower shooting skyward from the roof and visible for blocks. The station’s newscasters were well-known personalities and zipped through town to run down breaking news in the KENI Kamper, a squat camping trailer retrofitted into a mobile studio.

They were covering a city still in the process of inventing itself. Anchorage had been established only fifty years earlier, in 1915, when a couple thousand workers arriving to build the Alaska railroad pitched a huddle of tents on the shores of Ship Creek. The population had exploded at the start of the Cold War, sparked by military buildup at the army and air force bases north of town, but it wasn’t until 1959, when the territory of Alaska became America’s forty-ninth state, that the society Alaskans were building started to feel more secure. Before long, Anchorage was being described as the fastest-growing city in America, possibly in the world.

Copyright © 2020 by Jon Mooallem. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.