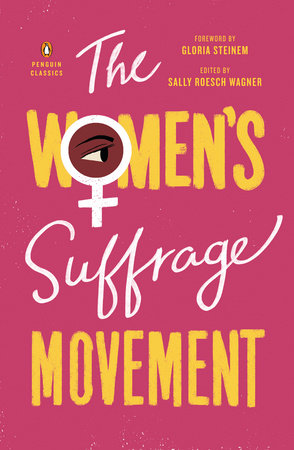

With The Women’s Suffrage Movement, Sally Roesch Wagner has given us a unique gift: the real words and actions, writings and debates, of white and black women who fought for over a century to gain an identity as free human beings and citizens.

For most of those years, black women were legally owned as chattel, forced to work and to suffer the unique punishment of giving birth to children who were also enslaved. White women were not as restricted and endangered as the women or men brought as slaves from Africa. But as the daughters and wives of white men, they were also legal chattel, with no right to leave their homes, disobey orders, profit from their own work, speak in public, have custody of their own children, own property without a guardian, or affect the patriarchal laws that governed their lives.

Even many, or most, white men who fought against slavery supported this subordinate position of their wives and daughters. When Susan B. Anthony, an abolitionist and suffragist, supported not only runaway slaves, but white wives escaping their violent husbands, even male abolitionist allies warned her that she was going too far.

As Frederick Douglass, a freed slave, abolitionist, and suffragist himself, wrote in his autobiography: “When the true history of the antislavery cause shall be written, women will occupy a large space in its pages, for the cause of the slave has been peculiarly women’s cause.”

And this despite the fact that many white women, especially but not only in the South, aided and abetted black slavery, and also accepted their own subordinate position as natural.

A century later, Gunnar Myrdal would explain in his landmark study of slavery that enslaved African women and men brought to these shores had been given the legal status of wives as the “nearest and most natural analogy” to the status of slaves. As he added, “The parallel between women and Negroes is the deepest truth of American life, for together they form the unpaid or underpaid labor on which America runs.”

Wagner takes us into the rooms, writings, and discussions where white and black women and black men, all fighting for legal personhood and full citizenship, were both a miracle of shared purpose, despite all the lethal forces keeping them apart, and later a tragedy of division that echoes in the need for intersectionality and inclusion to this day.

Even the lynchings of black men, crimes designed to maintain the racial order after the Civil War, were most often justified by proximity to white women, however imaginary or freely chosen. This tells us how dangerous and brave was the coalition for universal adult suffrage that you will read about here. It also reveals the betrayal when white men split the coalition apart by offering the vote to black men first, only to then limit their votes with poll taxes, impossible literacy tests, and violence.

Yet despite this tragic division, and despite being labeled as varying degrees of nonhuman, this fractious rebellion and fragile coalition did eventually succeed in gaining citizenship for the majority of people in this country.

Wagner brings us these imperfect and hopeful rebellions of the past as they happened, complete with their courage, divisions, and debates, plus a long organizational disagreement among women suffragists about whether to seek the vote by federal amendment or state by state.

She doesn’t attempt to prove a thesis, or to explain mistakes, or to excuse destructive divisions. Other than in the first and last chapters—each one with a very specific purpose—she doesn’t insert herself at all. Instead, she allows us to witness the words and acts, dreams and disappointments, victories and defeats, visionary ideas and tactical errors, of people fighting a battle that laid the basis for our continuing movement against hierarchies based on race and gender.

It is this faithfulness to the past that allows us to learn lessons for changes in the present and future.

In thirty or so years, this will no longer be a majority white country. It will better reflect the diversity that has always been its strength and its promise. Indeed, the first generation that is majority babies of color has already been born, and public opinion polls already show that the majority of Americans no longer support divisions by race and gender. Yet there is also a lethal backlash from about a third of the country—including over half of white married women, often also those without a college education and most likely to be dependent on a husband’s identity and income—who feel the need to preserve their unearned place in the social and economic hierarchy.

That’s why these victories and defeats of the past become the best possible lessons and warnings for our present and future. By taking us into the rooms where history happened, Wagner allows us to see the parallels and differences, empathy and estrangements, connections and isolations, that can hinder or help our shared goals now.

Almost none of the people we meet in these pages will live to celebrate the changes they are working for. This should tell us that social justice movements are not a temporary part of our lives, they are our lives. Most of the activists here were not sure that slavery would be abolished, or that universal adult suffrage would ever succeed. This should give us humility about what we can predict, and also arm us with faith and patience.

Few guessed that the legal right to vote would come a half century later for white and black women than for black men, but would be mostly on paper. In the South where most black Americans live, it would take another century plus an entire civil rights movement to overcome procedural and sometimes violent and lethal barriers to voting. This should make us skeptical about changes that come from the top, and that divide us more than they empower us.

And there are other lessons. For instance, decisions can’t be made for an unknown future, but we can create an inclusive and democratic way of making decisions. The ends don’t justify the means: in real life, the means we choose dictate the ends we get. Most of all, we are still experiencing the scars of divisions based on race and gender; divisions that didn’t have to be, and seem not to have existed before Europeans arrived, and conquered or killed most of the advanced cultures already here.

Fortunately, Wagner in her first chapter sends us off with unique encouragement. Unlike almost every other historian, she doesn’t treat this country as if it began with Columbus. We are not led to assume that gender and race begin a hierarchy that is decreed by human nature.

On this subcontinent once known as Turtle Island, women’s expertise in agriculture and men’s expertise in hunting were once equally necessary and equally honored. Many languages had no gendered pronouns, no “he” and “she.” Children inherited their clan identity through their mothers. Women knew very well how to have or not have children, and men did not control women’s bodies as the means of reproduction. Male leaders were often chosen by female elders, who also decided when to go to war and when to make peace. The paradigm of society was not a hierarchy, but a circle. Human beings were seen as linked, not ranked.

It was the Iroquois Confederacy of six native nations, with layers of talking circles for decision-making, that inspired Benjamin Franklin to invite Iroquois advisors to the Constitutional Convention. Each of the thirteen colonies needed a degree of autonomy, but also a way to make mutual decisions. The Iroquois governance system, the oldest continuing democracy in the world, became a model for our Constitution. Yet the first thing those advisors asked was: Where are the women?

Perhaps one day, our schools will teach history that begins when people began. As it is, it is still likely to start when patriarchy, monotheism, and colonialism began. It is rare and important that this book opens by showing us that suffrage leaders were inspired by the example of free and equal Native American women.

Perhaps we may also learn that some African women came from matrilineal cultures, with herbal knowledge of contraceptives and abortifacients that has been well documented. We are discovering from modern public opinion polls and current elections that black women are almost twice as likely to sup- port all the issues of female equality as are white women. Per- haps some of that comes not only from the necessity of their independence, but also from the stories in their memory.

Now, media characterize the suffrage movement, and the modern women’s movement, as mostly the activity of white women. But with the growing record of Native American women as the inspiration for white suffragists, and with black women’s leadership and activism now better documented—from suffrage to the results of the last presidential election—such fiction cannot survive.

This is why we need to know our history. We walk into rooms of our past, and listen to the conversations. Only after we have had a chance to draw our own lessons and conclusions from events as they happened does Wagner give us her thoughts about what could and should have been—and what could be now.

As Paula Gunn Allen, Native American activist and Laguna Pueblo poet, wrote in The Sacred Hoop, “the root of oppression is the loss of memory.”

Copyright © 2019 by Gloria Steinem. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.