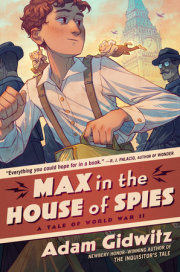

The king is ready for war.

Louis of France is not yet thirty, and already he is the greatest king in Europe. He loves his subjects. He loves God. And his armies have never been defeated.

This war, though, is different.

He is not fighting another army.

He is not fighting another king.

He is fighting three children. And their dog.

A week ago, Louis hadn’t heard of these three children. No one had. But now they are the most famous children in France. And the most wanted.

How did this happen?

That’s what I’m wondering.

It’s why I’m at the Holy Cross-Roads Inn, a day’s walk north of Paris. It’s early March, in the year of our Lord 1242. Outside, the sky is dark and getting darker. The wind is throwing the branches of an oak against the walls of the inn. The shutters are closed tight, to keep the dark out.

It’s the perfect night for a story.

The inn is packed. Butchers and brewers, peasants and priests, knights and nobodies. Everyone’s here to see the king march by. Who knows? Maybe we’ll see the children, too. And that dog of theirs. I would really like to see that dog.

I’m sitting on a wobbly stool at a rough, wooden table. It’s sticky with spilled ale.

“So!” I say, rubbing my hands together. “Does anyone know anything about these kids? The wanted ones? With the dog?”

The table practically erupts.

They’re all trying to tell me at once.

Beside me is a woman with thick arms, brown hair, and brown teeth. Her name is Marie, and she’s a brewster, a beer maker. I ask her where she’s from. She tells me she’s from the town of Saint-Geneviève.

“That’s where the girl is from!” I say. “Did you know her? Before she became famous?”

“Know her?” Marie says, indignant. “I practically raised her! Well, I didn’t raise her, but I know her real well.”

She smiles with her brown teeth at me. I smile back.

“Okay,” I say. “Let’s hear about her, then.”

And so Marie tells us all about the most famous girl in France.

The one the king has declared war on.

CHAPTER ONE

Jeanne’s story starts when she was a baby.

Her mother and father were regular peasants. Spent all day in the fields, just like most of the folks in our town. But there was one thing that made them special. They had this dog. A beautiful dog. A white greyhound, with a copper blaze down its nose. They called her Gwenforte—which is a ridiculous name for a dog, if you ask me. But they never did ask me, so that’s what they called her.

They loved Gwenforte. And they trusted her.

And so one day they went off to the fields to work, and they left baby Jeanne with Gwenforte.

“What?” I interrupt. “They used a dog as a babysitter?”

“Well . . . Yes. I suppose they did.”

“Is that normal? For peasants? To use dogs as babysitters?”

“No. I suppose it ain’t. But she was a real good dog.”

“Oh. That explains it.”

You gotta understand: Gwenforte loved that little girl so much, and was so protective of her, that nobody worried about it.

But maybe we should have.

For as Jeanne’s folks were out in the fields, working in the hot sun, a snake slithered into their house. It was an adder, with beady eyes and black triangles down its back. The day was hot, as I said, but the house was cool and dark because the walls in our houses are thick, made of mud and straw, and the only window is the round hole in the roof, where the smoke from the cooking fire escapes.

The adder, poisonous and silent as the Devil himself, slithered in through the space between the thin wooden door and the mud floor.

The baby girl lay asleep in her bed of straw. Gwenforte, the greyhound, was curled up around her.

But when the snake came in, Gwenforte sat up.

She growled.

She leapt onto the mud floor, right in front of the snake.

The adder stopped. Its forked tongue tested the air.

Gwenforte’s fur stood up on her back. She growled, low and deep in her throat.

The adder recoiled. He became a zigzag on the floor.

Gwenforte growled again.

The adder struck.

Adders, as you may know, are very fast.

But so are greyhounds.

Gwenforte shimmied out of the way just in time and snapped her jaws shut on the back of the adder’s neck. Then she began to shake the snake. She danced around the one-room house, shaking and shaking that snake, until the hay of the beds was scattered and the stone circle of the fire was ruined and the adder’s back was broken. Finally she tossed its carcass into a corner.

Jeanne’s parents were coming home from the fields just then. They were sweaty and tired. They had been up since long before sunrise. Their eyelids were heavy, and their arms and backs ached.

They pushed open the door of their little house. As the yellow light of summer streamed into the darkness, they saw the straw of the beds scattered all over the floor. They saw the fire circle, ruined. They saw Gwenforte, standing in the center of the dark room, panting, her tail wagging, her head high with pride—completely covered in blood.

What they did not see was their baby girl.

Well, they got panicked. They figured the worst. So they took that dog outside. And they killed her.

“Wait!” I cry. “But the dog—the dog isn’t dead! It’s alive!”

“It was dead,” says Marie. “Now it’s alive.”

I open my mouth and no sound comes out.

They come back into that house and try to put their lives back together. They were crying, a-course, because they loved that dog, and they loved their little girl even more. But we peasants know that life ain’t gonna stop for our tears. So they clean up. They put the embers back in the fire pit, they pick up the straw from the beds. And that’s when they see her. Baby Jeanne. Lying asleep in the hay. And in a corner, the dead snake.

Well, they picked up their daughter and held her tight and cried for joy. And after a little bit of that, they looked at each other, mother and father, and realized the horrible mistake they had made.

So they took the body of Gwenforte, and they buried her out in a beautiful grove in the forest, a short walk from the village. They dug up purple crocuses and planted them all around her grave. As the years went by, we started to venerate that dog proper, like the saint she is. Every time a new baby was born, they’d always go out to the Holy Grove, and pray to Saint Gwenforte, the Holy Greyhound, to keep that baby safe.

Well, years passed, and baby Jeanne grew and grew. She was a happy little thing. She liked to run down the long dirt road of the village, stopping into the dark doorways, waving to the people who lived inside each house. She came and saw me and helped me stir the hops in my old oak barrel. She visited Peter the priest, who lived with his wife, Ygraine—even though he’s not supposed to have a wife, on account of him being a priest. She would stop by and see Marc son of Marc, who had a little boy named Marc, too. She didn’t visit with Charles the bailiff, though—who’s my brother-in-law—because in addition to being our officer of the peace, he’s also about as kind as an old stick.

But of all the peasants in our town—and there were more than that, but I don’t want to bore you with long lists of people who don’t come into the story—Jeanne’s favorite was Old Theresa.

Old Theresa was a strange one. She collected frogs from the streams in the forest and put their blood in jars, to give to people when they were sick. She stared at the stars at night and told us our futures by how they moved. She was, I think it’s fair to say, a witch. But she was a nice old witch, and she was always kind to little Jeanne.

And then, one day, it turned out little Jeanne was just as strange as Theresa.

I was there the first time it happened. She couldn’t have been more than three years old. She was chasing Marc son-of-Marc son-of-Marc around my yard—when she stopped cold. She pulled up straight, like a stack of stones, and her eyes rolled back in her head. Then she went toppling to the ground, like somebody tipped that stack of stones over. She lay on the ground, and I saw her pudgy little arms and legs shaking, and her teeth grinding in her head. Scared the life out of me, it did. I ran screaming to Old Theresa, because she’s the only one not out in the fields. So we huddled over little Jeanne.

And then, the fit stopped. Jeanne’s breathing was ragged, but she weren’t shaking no more. Theresa bent over and roused the little girl. Cupped her wrinkled hand behind Jeanne’s head. Jeanne opened her eyes. Old Theresa asked her what happened, how she was feeling, that sort of thing. I’m leaning over them, wondering if Jeanne’s gonna be all right. And then Theresa asks, “Did you see something, little one?” I don’t know what she means.

But finally Jeanne’s face clears up, and she answers, “I saw the rain.”

And then, at that very moment, there’s a clap of thunder overhead and the sky opens up and the rain starts to fall.

I swear it on my very life.

I crossed myself about a hundred times, and was about to go tell the world the miracle I just witnessed, when Theresa grabbed my wrist.

She had milky blue eyes, Theresa did. She held my wrist tight. And she said, “Don’t you tell no one about what just happened.” The rain was running down the wrinkles in her face like they was streambeds. “Don’t you tell a soul. Not even her parents. Let me deal with it. Swear to me.”

Well, that’s a hard thing to ask—see a little girl perform a miracle and not tell her parents or no one about it. But when Old Theresa grabs your wrist and stares at you with those pale blue eyes . . . Well, I swore.

After that, Jeanne spent a lot of time with Theresa. She had more fits, but she never did see the future again. Or if she did, she didn’t tell no one what she saw.

Until one day, a few years later. I was with her and Theresa when Jeanne had another one of her fits—falling down, shaking, eyes rolling back in her head—and when she woke up, she said there was a giant coming. Theresa said that was nonsense and to hush. There were no giants in this part of France. But she said it again and again. I couldn’t figure out why she was saying all this in front of me. Hadn’t Theresa told her to keep her mouth shut?

But then Jeanne said that the giant was coming to take away Old Theresa.

That scared us. I admit it. Theresa got real quiet when she heard that.

The next day, sure enough, the giant came. I don’t know if he were really a giant or just the biggest man I’d ever seen. But Marc son-of-Marc father-of-Marc, who’s the tallest man in our town, only came up to the middle of his chest. The giant had wild red hair sticking up from his pate and wild red whiskers sticking out from his jowls. And he wore black robes—the black robes of a monk.

He called himself Michelangelo. Michelangelo di Bologna.

Little Jeanne had been working with her parents in the fields when word spread that the giant was come. She came to the edge of the fields. She saw the giant striding toward the village, his black robes billowing behind him.

Walking toward the giant, through the village, was my idiot brother-in-law, Charles the bailiff. He had Theresa by the arm, and he was bellowing some nonsense about new laws about rooting out heresy and pagan sorcery and some other fancy phrases he had just learned that week, I reckoned. He bowed deeply to the giant and then shoved Theresa at him, like she were a leper. The giant grabbed her thin wrist and began dragging Old Theresa out of town.

Jeanne ran down from the edge of fields. “Charles!” she shouted. “What’s happening? What’s he doing with Theresa?”

Charles spoke as if Jeanne were a small child. “I don’t know. But I imagine Michelangelo di Bologna is going to take her back to the holy Monastery Saint-Denis and burn her at the stake for pagan magic—for witchcraft. Burn her alive. Which is good and right and as it should be, my little pear pie.”

Little Jeanne cast a look of hatred so pure and deep at Charles that I don’t think he’s forgotten it to this day. I know I haven’t. Then she went sprinting out onto the road after the giant and Theresa, screaming and shouting, telling that giant to give Theresa back. You’ve never seen a girl so fierce and ferocious. “Give her back!” she cried. “Give her back!”

Old Theresa turned around. Her wrinkled face contorted with fear when she saw what little Jeanne was doing. “Jeanne!” she hissed. “Go! Quiet! Go back!”

But Jeanne would not quiet. “You stupid giant!” she screamed. She came up right behind them. “Stop it! Stop it you . . . you red . . . fat . . . wicked . . . giant!”

Slowly, the monk turned around.

His shadow engulfed the little girl.

He gazed down at her, his pale red eyes vaguely curious.

Jeanne looked right back up at him, like David facing Goliath. Except this Goliath looked like he was on fire.

And then the monk did something very frightening indeed.

He laughed.

He laughed at little Jeanne.

Then he dragged Old Theresa away.

And we never saw her again.

Jeanne ran home, her tears flying behind her. She threw open the thin wooden door of her house, collapsed on her bed, and cried.

Her mother came in just after her. Her footsteps were soft and reassuring on the dirt floor. She lowered herself onto the hay beside Jeanne and began to stroke her hair. “What’s wrong, my girl?” she asked. “Are you scared for Theresa?” She ran her fingers through Jeanne’s tangled locks.

Jeanne turned over and looked through tears up at her mother. Her mother had a skin-colored mole just to the left of her mouth and mousy, messy hair like her daughter’s. After a moment, Jeanne said, “I don’t want to be burned alive.”

Her mother’s face changed. “Why would you be burned alive, Jeanne?”

Jeanne stared up at her mother. Her vision had come true. Wasn’t that witchcraft?

Her mother’s face came into focus. It wasn’t comforting anymore. It looked . . . angry. “Why would you be burned, Jeanne? Tell me!”

Jeanne hesitated. “I don’t know,” she mumbled. And she buried her face in the hay again.

“Why, Jeanne? Jeanne, answer me!”

But Jeanne was too afraid to speak.

From that day on, Jeanne was different. She still had her fits, a-course, but she never opened her mouth about what she saw. Not once. More than that, she weren’t the happy little girl anymore. No more poking her head in our huts or chasing Marc son-of-Marc son-of-Marc around. She got seriouser. More watchful. Almost like she were scared. Not of other people, though.

Like she were scared of herself.

And then, about a week ago, some men came to our village, and they took Jeanne away.

“And that’s the end of my story.”

I’m in the midst of taking a quaff of my ale and I nearly spit it all over the table.

“What?! That’s it? They took her away? Why?” I sputter. “Who were they? And what about the dog? How did it come back to life?!”

“I can tell you.”

This isn’t Marie’s voice. It’s a nun at the next table. She’s been listening to the story, obviously, and now she’s leaning back on her little stool. “I know about Gwenforte and about the men who took little Jeanne.” She’s a tiny old woman, with silvery hair and bright blue eyes. And her accent is strange. It’s as proper as any I’ve ever heard. But it’s a little . . . off. I can’t quite say why.

“How would you know about Gwenforte and Jeanne?” Marie says. “You ain’t never even been in our village!”

“But I do know,” answers the nun.

“Then please,” I say, “tell us.”

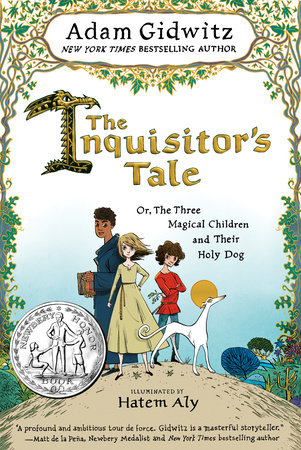

Copyright © 2016 by Adam Gidwitz; interior decorations by Hatem Aly. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.