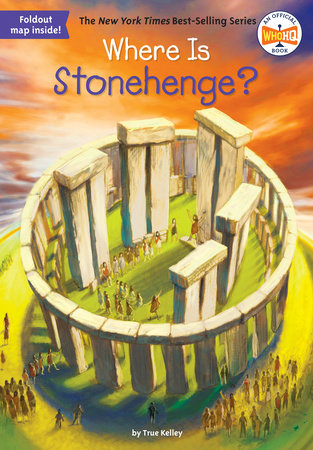

Where Is Stonehenge? Salisbury, England

In the 1830s, a group of four friends climbed out of a horse-drawn carriage. The ladies and gentlemen had come up with an interesting idea for the weekend. But now they were stiff and tired from traveling all day from London. Tourists often came to Salisbury to see the cathedral. It had the tallest spire in the country. But this group had planned a different adventure.

After resting overnight in town, they crowded into a small carriage and were driven across the countryside. They closed the blinds on the carriage windows so they couldn’t see out. Why?

At the end of their journey, they would reach a very special place. They wanted it to be a total surprise. So, in a giddy mood, they traveled on in darkness. It was bumpy, and the carriage seemed to be going very fast. Finally, the driver pulled the horses to a stop and told the passengers to open the blinds.

Everyone gasped at what they saw! The carriage was parked among giant stones standing in a circle. Some stones had fallen on the ground and were broken. But the stones still standing were taller than three men . . . What was this strange and amazing place called?

Stonehenge!

Some of the standing stones had other huge stones across the top of them. They looked like giant door frames. It was hard to imagine how people could have built such a thing thousands of years ago. Many people thought it had to be made by giants or by magic.

The tourists stood awestruck in the middle of the circle. They had seen paintings of this place and read poetry about it. Being there in person was very different. Even in a group of friends, there was a feeling of loneliness. There was not a tree in sight. The almost-flat land seemed to go on forever. The circle of stones appeared to jut out from the emptiness around them.

The wind blew cold, and gray clouds raced across the sky. Even with the wind, it was very quiet. Quiet and mysterious.

People have wondered about Stonehenge for more than a thousand years. How old is it? Where did the stones come from? Who built it and why? And how

? Unlike the Great Pyramids of Egypt, which are almost as old, there is no ancient written record of Stonehenge. But like the Great Pyramids, we know Stonehenge must have been important to ancient people because it took such great effort to build.

Now, with modern technology, archaeologists have learned almost as much in the last fifteen years as they knew for centuries before. (Archaeologists study objects from the past to find out about the people of long ago.) But many mysteries still remain. Those mysteries make Stonehenge one of the most fascinating places in the world.

Chapter 1: Circles of Stones In the south of England, about ninety miles west of London, sits the Salisbury Plain. It is a lonely-looking area. There are few trees. Not much grows except grass. Few creatures live there except sheep. Yet the Salisbury Plain is famous. Well over a million people travel there every year. They come from all over the world to visit one of the great monuments of the ancient world—the stone circle called Stonehenge.

Stonehenge sits at the top of a slight slope. Because the Salisbury Plain is so bare, Stonehenge can be seen from miles away. Lichen-covered stones seven feet wide and fourteen feet tall form a huge circle about one hundred feet across. That’s as wide as two basketball courts. The stones are a hard brown sandstone called sarsen. The sarsen stones were carved so that they are narrower at the top. This makes them look even taller than they really are. The stones are buried at different depths so that the tops are level with each other. Seventeen of these stones still stand. Many others have fallen and lie about on the ground.

Connecting some of the standing sarsen stones are ten-foot-long stone beams. They are called lintel stones because they are like the lintel, or crosspiece, of a door frame. At one time, lintel stones linked all the standing stones in the one-hundred-foot-wide circle.

The circle of sarsen stones is what visitors first see. Inside that circle is another circle of stones. They are half as tall and turn bluish when wet, so they are called bluestones. There are only six now, although once there may have been as many as sixty bluestones. The bluestones were put up after the sarsens.

Within the bluestones, nearer the center of the monument, three enormous trilithons (TRY-lith-ons) stand with part of a fourth. Trilithons are sets of three stones, two upright with a stone across them. There used to be a fifth trilithon, but it has disappeared. Another mystery!

The largest is called the Great Trilithon. Only one of its standing stones is still upright. The trilithons form a horseshoe forty-five feet across. Inside the horseshoe are the remains of another horseshoe of six-foot-high bluestones.

And finally, in the very center, is a sixteen-foot-long slab of gray-green sandstone. It lies flat and broken in two pieces. At one time archaeologists thought it was used as an altar in ceremonies. So it is called the Altar Stone. But like so much about Stonehenge, that is not at all certain. More likely, it was a standing stone that simply fell over.

Around the stones is a ditch and bank with a thirty-five-foot-wide entrance, which is called the Causeway. Near it lies the Slaughter Stone. This giant slab of bumpy rock got its name because it is stained red. People thought that the color came from the blood of animals or people sacrificed during ancient ceremonies. But now we know that the rock has iron in it. That’s what makes it red.

The Causeway leads to what remains of a wide two-mile-long dirt road. It is called the Avenue, and it curves down to the River Avon. Long, long ago, many travelers reached the stone circles from the river. As they turned the corner of the Avenue there would suddenly have been an awesome view of the giant stones.

One important sarsen stone stands outside the stone circle in the middle of the Avenue. It’s called the Heel Stone. On the longest day of the year, around June 21, the sun rises right over this sixteen-foot-high stone. The people of ancient times put it there on purpose. Marking and celebrating the longest day had to be very important to them.

The stones of Stonehenge still draw thousands of people on the longest day of summer. People are still in awe as they approach the stones. It’s an amazing sight, but there is much more to it than meets the eye.

Copyright © 2016 by True Kelley; Illustrated by John Hinderliter. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.