Chapter One

Kitty Coleman

I woke this morning with a stranger in my bed. The head of blond hair beside me was decidedly not my husband's. I did not know whether to be shocked or amused.

Well, I thought, here's a novel way to begin the new century.

Then I remembered the evening before and felt rather sick. I wondered where Richard was in this huge house and how we were meant to swap back. Everyone else here—the man beside me included—was far more experienced in the mechanics of these matters than I. Than we. Much as Richard bluffed last night, he was just as much in the dark as me, though he was more keen. Much more keen. It made me wonder.

I nudged the sleeper with my elbow, gently at first and then harder until at last he woke with a snort.

"Out you go," I said. And he did, without a murmur. Thankfully he didn't try to kiss me. How I stood that beard last night I'll never remember—the claret helped, I suppose. My cheeks are red with scratches.

When Richard came in a few minutes later, clutching his clothes in a bundle, I could barely look at him. I was embarrassed, and angry too—angry that I should feel embarrassed and yet not expect him to feel so as well. It was all the more infuriating that he simply kissed me, said, "Hello, darling," and began to dress, I could smell her perfume on his neck.

Yet I could say nothing. As I myself have so often said, I am open minded—I pride myself on it. Those words bite now.

I lay watching Richard dress, and found myself thinking of my brother. Harry always used to tease me for thinking too much—though he refused to concede that he was at all responsible for encouraging me. But all those evenings spent reviewing with me what his tutors had taught him in the morning—he said it was to help him remember it—what did that do but teach me to think and speak my mind? Perhaps he regretted it later. I shall never know now. I am only just out of mourning for him, but some days it feels as if I am still clutching that telegram.

Harry would be mortified to see where his teaching has led. Not that one has to be clever for this sort of thing—most of them downstairs are stupid as buckets of coal, my blond beard among them. Not one could I have a proper conversation with—I had to resort to the wine.

Frankly I'm relieved not to be of this set—to paddle in its shallows occasionally is quite enough for me. Richard I suspect feels differently, but he has married the wrong wife if he wanted that sort of life. Or perhaps it is I who chose badly—though I would never have thought so once, back when we were mad for each other.

I think Richard has made me do this to show me he is not as conventional as I feared. But it has had the opposite effect on me. He has become everything I had not thought he would be when we married. He has become ordinary.

I feel so flat this morning. Daddy and Harry would have laughed at me, but I secretly hoped that the change in the century would bring a change in us all; that England would miraculously slough off her shabby black coat to reveal something glittering and new. It is only eleven hours into the twentieth century, yet I know very well that nothing has changed but a number.

Enough. They are to ride today, which is not for me—I shall escape with my coffee to the library. It will undoubtedly be empty.

Richard Coleman

I thought being with another woman would bring Kitty back, that jealousy would open her bedroom door to me again. Yet two weeks later she has not let me in any more than before.

I do not like to think that I am a desperate man, but I do not understand why my wife is being so difficult. I have provided a decent life for her and yet she is still unhappy, though she cannot—or will not—say why.

It is enough to drive any man to change wives, if only for a night.

Maude Coleman

When Daddy saw the angel on the grave next to ours he cried, "What the devil?"

Mummy just laughed.

I looked and looked until my neck ached. It hung above us, one foot forward, a hand pointing toward heaven. It was wearing a long robe with a square neck, and it had loose hair that flowed onto its wings. It was looking down toward me, but no matter how hard I stared it did not seem to see me.

Mummy and Daddy began to argue. Daddy does not like the angel. I don't know if Mummy likes it or not—she didn't say. I think the urn Daddy has had put on our own grave bothers her more.

I wanted to sit down but didn't dare. It was very cold, too cold to sit on stone, and besides, the Queen is dead, which I think means no one can sit down, or play, or do anything comfortable.

I heard the bells ringing last night when I was in bed, and when Nanny came in this morning she told me the Queen died yesterday evening. I ate my porridge very slowly, to see if it tasted different from yesterday's, now that the Queen is gone. But it tasted just the same—too salty. Mrs. Baker always makes it that way.

Everyone we saw on our way to the cemetery was dressed in black. I wore a gray wool dress and a white pinafore, which I might have worn anyway but which Nanny said was fine for a girl to wear when someone died. Girls don't have to wear black. Nanny helped me to dress. She let me wear my black-and-white plaid coat and matching hat, but she wasn't sure about my rabbit's-fur muff, and I had to ask Mummy, who said it didn't matter what I wore. Mummy wore a blue silk dress and wrap, which did not please Daddy.

While they were arguing about the angel I buried my face in my muff. The fur is very soft. Then I heard a noise, like stone being tapped, and when I raised my head I saw a pair of blue eyes looking at me from over the headstone next to ours. I stared at them, and then the face of a boy appeared from behind the stone. His hair was full of mud, and his cheeks were dirty with it too. He winked at me, then disappeared behind the headstone.

I looked at Mummy and Daddy, who had walked a little way up the path to view the angel from another place. They had not seen the boy. I walked backward between the graves, my eyes on them. When I was sure they were not looking I ducked behind the stone.

The boy was leaning against it, sitting on his heels.

"Why do you have mud in your hair?" I asked.

"Been down a grave," he said.

I looked at him closely. There was mud on him everywhere—on his jacket, on his knees, on his shoes. There were even bits of it in his eyelashes.

"Can I touch the fur?" he asked.

"It's a muff," I said. "My muff."

"Can I touch it?"

"No." Then I felt bad saying that, so I held out the muff.

The boy spit on his fingers and wiped them on his jacket, then reached out and stroked the fur.

"What were you doing down a grave?" I asked.

"Helping our pa."

"What does your father do?"

"He digs the graves, of course. I helps him."

Then we heard a sound, like a kitten mewing. We peeked over the headstone and a girl standing in the path looked straight into my eyes, just as I had with the boy. She was dressed all in black, and was very pretty, with bright brown eyes and long lashes and creamy skin. Her brown hair was long and curly and so much nicer than mine, which hangs flat like laundry and isn't one color or another. Grandmother calls mine ditch-water blond, which may be true but isn't very kind. Grandmother always speaks her mind.

The girl reminded me of my favorite chocolates, whipped hazelnut creams, and I knew just from looking at her that I wanted her for my best friend. I don't have a best friend, and have been praying for one. I have often wondered, as I sit in St. Anne's getting colder and colder (why are churches always cold?), if prayers really work, but it seems this time God has answered them.

"Use your handkerchief, Livy dear, there's a darling." The girl's mother was coming up the path, holding the hand of a younger girl. A tall man with a ginger beard followed them. The younger girl was not so pretty. Though she looked like the other girl, her chin was not so pointed, her hair not so curly, her lips not so big. Her eyes were hazel rather than brown, and she looked at everything as if nothing surprised her. She spotted the boy and me immediately.

"Lavinia," the older girl said, shrugging her shoulders and tossing her head so that her curls bounced. "Mama, I want you and Papa to call me Lavinia, not Livy."

I decided then and there that I would never call her Livy.

"Don't be rude to your mother, Livy," the man said. "You're Livy to us and that's that. Livy is a fine name. When you're older we'll call you Lavinia."

Lavinia frowned at the ground.

"Now stop all this crying," he continued. "She was a good queen and she lived a long life, but there's no need for a girl of five to weep quite so much. Besides, you'll frighten Ivy May." He nodded at the sister.

I looked at Lavinia again. As far as I could see she was not crying at all, though she was twisting a handkerchief around her fingers. I waved at her to come.

Lavinia smiled. When her parents turned their backs she stepped off the path and behind the headstone.

"I'm five as well," I said when she was standing next to us. "Though I'll be six in March."

"Is that so?" Lavinia said. "I'll be six in February."

"Why do you call your parents Mama and Papa? I call mine Mummy and Daddy."

"Mama and Papa is much more elegant." Lavinia stared at the boy, who was kneeling by the headstone. "What is your name, please?"

"Maude," I answered before I realized she was speaking to the boy.

"Simon."

"You are a very dirty boy."

"Stop," I said.

Lavinia looked at me. "Stop what?"

"He's a gravedigger, that's why he's muddy."

Lavinia took a step backward.

"An apprentice gravedigger," Simon said. "I was a mute for the undertakers first, but our pa took me on once I could use a spade."

"There were three mutes at my grandmother's funeral," Lavinia said. "One of them was whipped for laughing."

"My mother says there are not so many funerals like that anymore," I said. "She says they are too dear and the money should be spent on the living."

"Our family always has mutes at its funerals. I shall have mutes at mine."

"Are you dying, then?" Simon asked.

"Of course not!"

"Did you leave your nanny at home as well?" I asked, thinking we should talk about something else before Lavinia got upset and left.

She flushed. "We don't have a nanny. Mama is perfectly able to look after us herself."

I didn't know any children who didn't have a nanny.

Lavinia was looking at my muff. "Do you like my angel, then?" she asked. "My father let me choose it."

"My father doesn't like it," I declared, though I knew I shouldn't repeat what Daddy had said. "He called it sentimental nonsense."

Lavinia frowned. "Well, Papa hates your urn. Anyway, what's wrong with my angel?"

"I like it," the boy said.

"So do I," I lied.

"I think it's lovely." Lavinia sighed. "When I go to heaven I want to be taken up by an angel just like that."

"It's the nicest angel in the cemetery," the boy said. "And I know 'em all. There's thirty-one of 'em. D'you want me to show 'em to you?"

"Thirty-one is a prime number," I said. "It isn't divisible by anything except one and itself." Daddy had just explained to me about prime numbers, though I hadn't understood it all.

Simon took a piece of coal from his pocket and began to draw on the back of the headstone. Soon he had drawn a skull and crossbones—round eye-sockets, a black triangle for a nose, rows of square teeth, and a shadow scratched on one side of the face.

"Don't do that," I said. He ignored me. "You can't do that."

"I have. Lots. Look at the stones all round us."

I looked at our family grave. At the very bottom of the plinth that held the urn, a tiny skull and crossbones had been scratched. Daddy would be furious if he knew it was there. I saw then that every stone around us had a skull and crossbones on it. I had never seen them before.

"I'm going to draw one on every grave in the cemetery," he continued.

"Why do you draw them?" I asked. "Why a skull and crossbones?"

"Reminds you what's underneath, don't it? It's all bones down there, whatever you may put on the grave."

"Naughty boy," Lavinia said.

Simon stood up. "I'll draw one for you," he said. "I'll draw one on the back of your angel."

"Don't you dare," Lavinia said.

Simon immediately dropped the piece of coal.

Lavinia looked around as if she were about to leave.

"I know a poem," Simon said suddenly.

"What poem? Tennyson?"

"Dunno whose son. It's like this:

There was a young man at Nunhead

Who awoke in his coffin of lead;

`It is cosy enough,'

He remarked in a huff,

`But I wasn't aware I was dead.'"

"Ugh! That's disgusting!" Lavinia cried. Simon and I laughed.

"Our pa says lots of people've been buried alive," Simon said. "He says he's heard 'em, scrabbling inside their coffins as he's tossing dirt on 'em."

"Really? Mummy's afraid of being buried alive," I said.

"I can't bear to hear this," Lavinia cried, covering her ears. "I'm going back." She went through the graves toward her parents. I wanted to follow her but Simon began talking again.

"Our granpa's buried here in the meadow."

"He never was."

"He is."

"Show me his grave."

Simon pointed at a row of wooden crosses over the path from us. Paupers' graves—Mummy had told me about them, explaining that land had been set aside for people who had no money to pay for a proper plot.

"Which cross is his?" I asked.

"He don't have one. Cross don't last. We planted a rosebush there, so we always know where he is. Stole it from one of the gardens down the bottom of the hill."

I could see a stump of a bush, cut right back for the winter. We live at the bottom of the hill, and we have lots of roses at the front. Perhaps that rosebush was ours.

"He worked here too," Simon said. "Same as our pa and me. Said it's the nicest cemetery in London. Wouldn't have wanted to be buried in any of t'others. He had stories to tell about t'others. Piles of bones everywhere. Bodies buried with just a sack of soil over 'em. Phew, the smell!" Simon waved his hand in front of his nose. "And men snatching bodies in the night. Here he were at least safe and sound, with the boundary wall being so high, and the spikes on top."

"I have to go now," I said. I didn't want to look scared like Lavinia, but I didn't like hearing about the smell of bodies.

Simon shrugged. "I could show you things."

"Maybe another time." I ran to catch up with our families, who were walking along together. Lavinia took my hand and squeezed it and I was so pleased I kissed her.

As we walked hand-in-hand up the hill I could see out of the corner of my eye a figure like a ghost jumping from stone to stone, following us and then running ahead. I wished we had not left him.

I nudged Lavinia. "He's a funny boy, isn't he?" I said, nodding at his shadow as he went behind an obelisk.

"I like him," Lavinia said, "even if he talks about awful things."

"Don't you wish we could run off the way he does?"

Lavinia smiled at me. "Shall we follow him?"

I hadn't expected her to say that. I glanced at the others—only Lavinia's sister was looking at us. "Let's," I whispered.

She squeezed my hand as we ran off to find him.

Kitty Coleman

I don't dare tell anyone or I will be accused of treason, but I was terribly excited to hear the Queen is dead. The dullness I have felt since New Year's vanished, and I had to work very hard to appear appropriately sober. The turning of the century was merely a change in numbers, but now we shall have a true change in leadership, and I can't help but think Edward is more truly representative of us than his mother.

For now, though, nothing has changed—we were expected to troop up to the cemetery and make a show of mourning, even though none of the Royal Family is buried there, nor is the Queen to be. Death is there, and that is enough, I suppose.

That blasted cemetery. I have never liked it.

To be fair, it is not the fault of the place itself, which has a lugubrious charm, with its banks of graves stacked on top of one another—granite headstones, Egyptian obelisks, Gothic spires, plinths topped with columns, weeping ladies, angels, and of course, urns—winding up the hill to the glorious Lebanon cedar at the top. I am even willing to overlook some of the more preposterous monuments—ostentatious representations of a family's status. But the sentiments that the place encourages in mourners are too overblown for my taste. Moreover, it is the Colemans' cemetery, not my family's. I miss the little churchyard in Lincolnshire where Mummy and Daddy are buried and where there is now a stone for Harry, even if his body lies somewhere in southern Africa.

The excess of it all—which our own ridiculous urn now contributes to—is too much. How utterly out of scale it is to its surroundings! If only Richard had consulted me first. It was unlike him—for all his faults he is a rational man, and must have seen that the urn was too big. I suspect the hand of his mother in the choosing. Her taste has always been formidable.

It was amusing today to watch him splutter over the angel that has been erected on the grave next to the urn. (Far too close to it, as it happens—they look as if they may bash each other at any moment.) It was all I could do to keep a straight face.

"How dare they inflict their taste on us!" he said. "The thought of having to look at this sentimental nonsense every time we visit turns my stomach."

"It is sentimental, but harmless," I replied "At least the marble's Italian."

"I don't give a hang about the marble! I don't want that angel next to our grave."

"Have you thought that perhaps they're saying the same about the urn?"

"There's nothing wrong with our urn!"

"And they would say that there's nothing wrong with their angel."

"The angel looks ridiculous next to the urn. It's far too close, for one thing."

"Exactly," I said. "You didn't leave them room for anything."

"Of course I did. Another urn would have looked fine. Perhaps a slightly smaller one."

I raised my eyebrows the way I do when Maude has said something foolish. "Or even the same size," Richard conceded. "Yes, that could have looked quite impressive, a pair of urns. Instead we have this nonsense."

And on and on we went. While I don't think much of the blank-faced angels dotted around the cemetery, they bother me less than the urns, which seem a peculiar thing to put on a grave when one thinks that they were used by the Romans as receptacles for human ashes. A pagan symbol for a Christian society. But then, so is all the Egyptian symbolism one sees here as well. When I pointed this out to Richard he huffed and puffed but had no response other than to say, "That urn adds dignity and grace to the Coleman grave."

I don't know about that. Utter banality and misplaced symbolism are rather more like it. I had the sense not to say so.

He was still going on about the angel when who should appear but its owners, dressed in full mourning. Albert and Gertrude Waterhouse—no relation to the painter, they admitted. (Just as well—I want to scream when I see his overripe paintings at the Tate. The Lady of Shalott in her boat looks as if she has just taken opium.) We had never met them before, though they have owned their grave for several years. They are rather nondescript—he a ginger-bearded, smiling type, she one of those short women whose waists have been ruined by children so that their dresses never fit properly. Her hair is crinkly rather than curly, and escapes its pins.

Her elder daughter, Lavinia, who looks to be Maude's age, has lovely hair, glossy brown and curly. She's a bossy, spoiled little thing—apparently her father bought the angel at her insistence. Richard nearly choked where he heard this. And she was wearing a black dress trimmed with crepe—rather vulgar and unnecessary for a child that young.

Of course Maude has taken an instant liking to the girl. When we all took a turn around the cemetery together Lavinia kept dabbing at her eyes with a black-edged handkerchief, weeping as we passed the grave of a little boy dead fifty years, I just hope Maude doesn't begin copying her. I can't bear such nonsense. Maude is very sensible but I could see how attracted she was to the girl's behavior. They disappeared off together—Lord knows what they got up to. They came back the best of friends.

I think it highly unlikely Gertrude Waterhouse and I would ever be the best of friends. When she said yet again how sad it was about the Queen, I couldn't help but comment that Lavinia seemed to be enjoying her mourning tremendously.

Gertrude Waterhouse said nothing for a moment, then remarked, "That's a lovely dress. Such an unusual shade of blue."

Richard snorted. We'd had a fierce argument about my dress. In truth I was now rather embarrassed about my choice—not one adult I'd seen since leaving the house was wearing anything but black. My dress was dark blue, but still I stood out far more than I'd intended

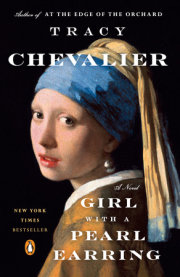

—Reprinted from Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier by permission of Plume, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002, Tracy Chevalier. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Copyright © 2002 by Tracy Chevalier. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.