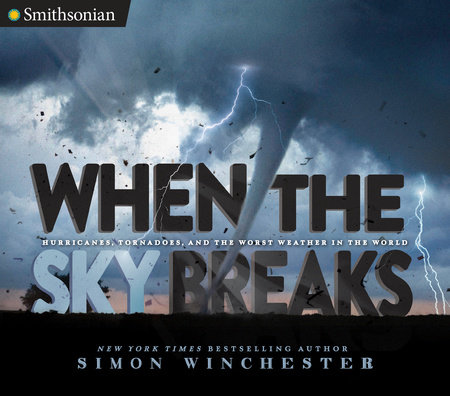

Chapter One

The Biggest, Baddest Weather

My experience of Hurricane Sandy—or Frankenstorm, the Blizzacane, the Snor’eastercane, or any of the other outlandish names the press chose to give to the most devastating American weather event of 2012—confirmed what I knew as a homegrown weatherman: when trouble is in the offing, listen very carefully to the weather forecast.

We had been living in a basement apartment in New York City that had flooded once before, so the likelihood of a major storm surge in lower Manhattan was alarming, to say the least. This alarm was reinforced by a passage from one of my recent books. My own words suggested that something terribly bad was about to happen:

New York sits on stable geological features that rise well above sea level, but it has been tunneled into and bored through until it resembles an ants’ nest, and all its tunnels lie well below sea level. A storm surge coming into New York Harbor could flood the subway lines without difficulty. But far more goes on underground than subways: the telecommunications cables and fiber-optic lines alone are vital for the running of the world’s financial industries: soak them in the water, and the world starts to fall apart.

Vulnerable cities are not merely going to slide slowly and elegantly under the sea, millimeter by millimeter. They are going to perch on the edge of inundation until a storm rages itself into an uncontrollable maelstrom of fury, and a battering of huge waves breaches the dykes and the levees, and water courses into the city center in torrents, destroying all before it.

By Thursday, October 25, 2012, all the computer forecasting models locked themselves into harmony. The predictions became more and more accurate, and the realization more and more acute: a giant storm would actually hit the hinterlands of New York City.

So we got out of town . . . and Sandy roared in.

***

Hurricane, the name by which this unimaginably huge and destructive weather system has been known in North America for the last three centuries, comes from the Carib word

huracán, meaning a “great wind.” In other parts of the world, these terrifying, majestic storms are called

cyclones or

typhoons, depending upon whether they circulate in a clockwise direction (as they do in the southern hemisphere) or in the opposite (counterclockwise) direction (in the northern hemisphere).

Cyclone comes from the Greek κυκλῶν,

kyklon, which translates to “whirling around in a circle”;

typhoon comes from the Chinese words for “big wind.”

Hurricane. Cyclone. Typhoon. What exactly are such giant storms? When, where, and how do they form? And why do such destructive forces even exist? To answer all these questions—an ongoing process, since weather science is an eternally evolving branch of knowledge—requires some very basic understanding of the Earth and the laws of physics that enfold it.

Though they may generate many headlines, hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons are in fact rather rare events. (For simplicity, I’ll just use the word

hurricane from now on to include all these violent weather monsters.) Only about ninety-six such storms occur every year; roughly a dozen are even named. Most days in the world’s tropics, where these storms begin, are pleasing and peaceful; the chances of being affected by a hurricane are quite small. But when the big storms do develop, they can be terrifying, and for centuries they were every bit as mysterious as earthquakes and volcanoes.

As with so many of the world’s violent phenomena, hurricanes were long believed to be an act of God. Up until the nineteenth century, no one had any real idea of what these storms were. They arrived from the sea, where they probably had formed, and they soaked and destroyed whatever they passed over on land, then moved on, leaving behind misery and mystery.

But in 1821 a Connecticut saddlemaker and part-time weatherman named William Redfield noticed something: the way trees had been felled by a huge storm that had just passed across his state differed significantly depending on where the trees were. Trees in the eastern corner of Connecticut, where the storm had first swept in from the Atlantic, had all fallen toward the northwest; but the trees in the far west of the state, where Connecticut meets New York, had fallen in a southeasterly direction. The astute Mr. Redfield surmised from this that the storm must have been a giant whirlwind—which is, of course, perfectly right.

Copyright © 2017 by Simon Winchester. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.