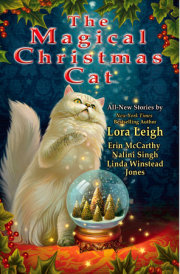

Upon a Midnight Clear

VIRGINIA KANTRA

To Carolyn Martin, who knows a thing or two about angels.

Chapter One

PARIS, FRANCE, DECEMBER 1792

The angel came down in the long gallery of the Conciergerie prison, the notorious antechamber to the guillotine.

Stone walls could not keep him out. Stench and darkness offered no deterrent. He was a child of the air, elemental, immortal, one of the First Creation. As long as he did not materialize completely, he could go anywhere.

Cold seeped through the blocked grates and up from the flagstones along with the miasma of human misery. The corridor was alive with sighs and sobs and vermin. In the bloody wake of revolution, the prisons of Paris were filled to bursting with the ci-devant aristocracy and their suspected sympathizers. Few had the money or influence to secure the comforts of a private incarceration, a bed, food, firewood, perhaps a chamber pot. Cells intended for one or two prisoners held four, six, a dozen men, women, and children, packed together on the filthy straw like so many bottles of wine.

In the stone blocks adjoining the exercise yard, some poor soul had scratched BIENVENUE EN ENFER. Welcome to Hell.

But this was not Hell. There were still those here who called on God in their distress. So the angel had come, drawn by a dying mother’s prayer to provide . . .

Not escape, the angel acknowledged. He felt the brush of some unusual emotion, threatening his angelic detachment. Frustration, perhaps.

The children of air were forbidden from interfering directly in worldly affairs. With rare exceptions, humans must work out their own fate, their own salvation. But the angel could offer comfort to ease the woman’s soul from this life to the next.

His frustration—if that’s what it was—deepened. Tonight, solace did not seem enough.

He flexed his shoulders at the admission, feeling a prickle between his shoulder blades. He was an angel of God. Comfort was his stock in trade. It must suffice.

A woman’s hoarse Latin slipped through the bars to hang like frost in the air. “Sancta Maria, Mater Domini nostri, ora pro nobis pec-catoribus.” Holy Mary, Mother of our Lord, pray for us sinners. “Nunc et in hora . . .” A cough. “Et in hora . . .”

More coughing, deep, wracking.

“Lie quiet, Maman.” A girl’s voice, sweet and clear and welcome as water in this dirty hole, speaking the King’s French. “You must save your breath.”

The angel followed the voice through the square iron grate into the cell. Two women—a woman and a girl, rather—huddled on the straw inside. The girl knelt on the brutally cold floor, supporting her mother’s shoulders, trying to ease her breathing.

The child was very pretty, the angel observed dispassionately, with a delicate nose, a heart-shaped faced blunted by a firm, rounded chin, and eyes as blue as an October sky. But it was the mother who had called him here. Citoyenne Solange Blanchard, former Comtesse de Brissac, convent bred and barely thirty.

“Nunc et in hora mortis nostrae,” the comtesse whispered. Now and at the hour of our death.

“Maman, you must rest,” the girl scolded gently. “You need your strength.”

The angel could have told the girl that no amount of rest would make any difference. The infection in the comtesse’s lungs had attacked her already weakened system.

But the girl’s tenderness moved him anyway.

He spread his power over the dying woman like wings, extending over her the peace of the presence of God.

Solange opened her eyes in the darkness, focusing on his face. “An angel,” she whispered. “Come to save us.”

He was hardly surprised that she could see him. She was very near death. “I cannot,” he told her gently.

Must not.

“Save her,” the woman insisted. Her daughter, thirteen-year-old Aimée. “When I am gone, she will be alone.”

The girl chafed her mother’s hands. “Maman, you must not upset yourself.” Doubtless the child believed the comtesse was talking to herself, out of her mind with fever and grief.

The whole country was mad. After centuries of privilege, the Old Regime was paying for its sins of pride and abuse of power. In three short years, the comtesse had been stripped of everything: lands, tithes, and titles. The life of her husband. Their son.

These humans went too far in redressing old wrongs. They had no concept of Heavenly justice, no understanding of divine mercy.

Comfort, the angel reminded himself.

“Your family will be reunited soon,” he assured Solange.

She would be dead by morning. And her daughter would follow, executed within the week, sacrificed to nationalist fervor and bloodlust.

Underneath the familiar flowering of compassion, anger stirred, like a worm at the heart of a rose.

Solange wet her dry lips. “One day. Not yet. You must . . .” Another cough rattled the comtesse’s frail frame. She met the angel’s gaze, the light of faith or determination in her eyes. “You will save her.”

Such faith should be rewarded.

Shouldn’t it?

“I will.” The words falling from his lips caught him by surprise.

He was an angel, bound to discern the will of God, to protect, and to obey. He regarded the dark sweep of the child’s lashes, the sheltering curve of her shoulders.

What if the charge to protect, the call to obey, pulled him in different directions?

He would be punished for his disobedience, of course. Not for the first time. Michael, leader of the Heavenly host, took a dim view of insubordination. But perhaps Gabriel would intercede for him. It was almost Christmas, after all. The season of miracles. There was some precedent for his intervention in human affairs.

“You promise,” Solange insisted.

Recklessness seized him. “I swear.”

The girl glanced up, almost as if she heard him. Those clear blue eyes narrowed. “Who are you?”

The angel jolted. She saw him? Was she that pure? That innocent? Or was she like her mother, close enough to death to feel the brush of his wings?

“The answer to our prayers,” Solange said.

“Can he get us out of here?” Aimée asked, direct as a child, pragmatic as any of her countrywomen.

“Of a surety he can save you,” Solange said. “You must go with him.”

The girl raised her head. He had no idea what she could make out in the dark. She should not have been able to see him at all.

“You will have to help my mother. She cannot stand.”

The angel held Solange’s gaze for a long moment.

“I do not go with you, mignonne,” the comtesse said softly.

Aimée stuck out her rounded chin. “Then we will not go.”

“My dear . . .” The comtesse coughed. “You have no choice.”

“I won’t leave you.” The girl’s voice rose, provoking glances and whispers from her fellow prisoners.

But the cell’s other inhabitants were too respectful of her grief, too fearful of fever or sunk in their own despair to intervene.

“I cannot remove her against her will,” the angel said.

“You promised to save her,” Solange said.

Irritation flickered through him, crackled like ozone in the air. Frustration with her, with himself, with the sins of men and the limitations of angels. “She does not wish to be rescued.”

Intervention was one thing. He might be forgiven for granting a dying mother’s prayer. But violating a human being’s free will was another, far more serious offense.

He looked at the girl, her springy dark curls, her clear, wide eyes, the jut of that childlike chin. She was old enough to make her own decisions.

His chest tightened. And far too young to die. Her goodness shone in this mortal Hell like a star.

Solange continued as if he had not spoken. “I have family in England. A cousin.” Her voice, her strength, flared and faded like a sullen fire. “Héloïse married an Englishman. Basing. Sir Walter Basing. You will . . . take my Aimée to them?”

“No,” the girl said fiercely. Her cheeks were flushed, her shoulders rigid. “It is my life. My choice.”

Stubborn. He would need to silence her to get her past the prison guards.

He did not look forward to taking solid form, to descending into the flesh and the stink and the pain of human existence to lug her through the barricades. He dare not save them all.

But the girl would live. She would be safe in England. He would be damned before he’d let this child’s light be extinguished.

His lip curled. He might be damned, anyway.

He breathed on the girl, catching her slight body as she slumped.

They didn’t have much time.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.