“He was afraid to look back . . .”

Zhenya Belkevich

Six years old. Now a worker.

June 1941 . . .

I remember it. I was very little, but I remember everything . . .

The last thing I remember from the peaceful life was a fairy tale that mama read us at bedtime. My favorite one—about the Golden Fish. I also always asked something from the Golden Fish: “Golden Fish . . . Dear Golden Fish . . .” My sister asked, too. She asked differently: “By order of the pike, by my like . . .” We wanted to go to our grandmother for the summer and have papa come with us. He was so much fun.

In the morning I woke up from fear. From some unfamiliar sounds . . .

Mama and papa thought we were asleep, but I lay next to my sister pretending to sleep. I saw papa kiss mama for a long time, kiss her face and hands, and I kept wondering: he’s never kissed her like that before. They went outside, they were holding hands, I ran to the window—mama hung on my father’s neck and wouldn’t let him go. He tore free of her and ran, she caught up with him and again held him and shouted something. Then I also shouted: “Papa! Papa!”

My little sister and brother Vasya woke up, my sister saw me crying, and she, too, shouted: “Papa!” We all ran out to the porch: “Papa!” Father saw us and, I remember it like today, covered his head with his hands and walked off, even ran. He was afraid to look back.

The sun was shining in my face. So warm . . . And even now I can’t believe that my father left that morning for the war. I was very little, but I think I realized that I was seeing him for the last time. That I would never meet him again. I was very . . . very little . . .

It became connected like that in my memory, that war is when there’s no papa . . .

Then I remember: the black sky and the black plane. Our mama lies by the road with her arms spread. We ask her to get up, but she doesn’t. She doesn’t rise. The soldiers wrapped mama in a tarpaulin and buried her in the sand, right there. We shouted and begged: “Don’t put our mama in the ground. She’ll wake up and we’ll go on.” Some big beetles crawled over the sand . . . I couldn’t imagine how mama was going to live with them under the ground. How would we find her afterward, how would we meet her? Who would write to our papa?

One of the soldiers asked me: “What’s your name, little girl?” But I forgot. “And what’s your last name, little girl? What’s your mother’s name?” I didn’t remember . . . We sat by mama’s little mound till night, till we were picked up and put on a cart. The cart was full of children. Some old man drove us, he gathered up everybody on the road. We came to a strange village and strangers took us all to different cottages.

I didn’t speak for a long time. I only looked.

Then I remember—summer. Bright summer. A strange woman strokes my head. I begin to cry. I begin to speak . . . To tell about mama and papa. How papa ran away from us and didn’t even look back . . . How mama lay . . . How the beetles crawled over the sand . . .

The woman strokes my head. In those moments I realized: she looks like my mama . . .

“My first and last cigarette . . .”

Gena Yushkevich

Twelve years old. Now a journalist.

The morning of the first day of the war . . .

Sun. And unusual quiet. Incomprehensible silence.

Our neighbor, an officer’s wife, came out to the yard all in tears. She whispered something to mama, but gestured that they had to be quiet. Everybody was afraid to say aloud what had happened, even when they already knew, since some had been informed. But they were afraid that they’d be called provocateurs. Panic-mongers. That was more frightening than the war. They were afraid . . . This is what I think now . . . And of course no one believed it. What?! Our army is at the border, our leaders are in the Kremlin! The country is securely protected, it’s invulnerable to the enemy! That was what I thought then . . . I was a young Pioneer.

We listened to the radio. Waited for Stalin’s speech. We needed his voice. But Stalin was silent. Then Molotov gave a speech. Everybody listened. Molotov said, “It’s war.” Still no one believed it yet. Where is Stalin?

Planes flew over the city . . . Dozens of unfamiliar planes. With crosses. They covered the sky, covered the sun. Terrible! Bombs rained down . . . There were sounds of ceaseless explosions. Rattling. Everything was happening as in a dream. Not in reality. I was no longer little—I remember my feelings. My fear, which spread all over my body. All over my words. My thoughts. We ran out of the house, ran somewhere down the streets . . . It seemed as if the city was no longer there, only ruins. Smoke. Fire. Somebody said we must run to the cemetery, because they wouldn’t bomb a cemetery. Why bomb the dead? In our neighborhood there was a big Jewish cemetery with old trees. And everybody rushed there, thousands of people gathered there. They embraced the monuments, hid behind the tombstones.

Mama and I sat there till nightfall. Nobody around uttered the word war. I heard another word: provocation. Everybody repeated it. People said that our troops would start advancing any moment. On Stalin’s orders. People believed it.

But the sirens on the chimneys in the outskirts of Minsk wailed all night . . .

The first dead . . .

The first dead I saw was a horse . . . Then a dead woman . . . That surprised me. My idea was that only men were killed in war.

I woke up in the morning . . . I wanted to leap out of bed, then I remembered—it’s war, and I closed my eyes. I didn’t want to believe it.

There was no more shooting in the streets. Suddenly it was quiet. For several days it was quiet. And then all of a sudden there was movement . . . There goes, for instance, a white man, white all over, from his shoes to his hair. Covered with flour. He carries a white sack. Another is running . . . Tin cans fall out of his pockets, he has tin cans in his hands. Candy . . . Packs of tobacco . . . Someone carries a hat filled with sugar . . . A pot of sugar . . . Indescribable! One carries a roll of fabric, another goes all wrapped in blue calico. Red calico . . . It’s funny, but nobody laughs. Food warehouses had been bombed. A big store not far from our house . . . People rushed to take whatever was left there. At a sugar factory several men drowned in vats of sugar syrup. Terrible! The whole city cracked sunflower seeds. They found a stock of sunflower seeds somewhere. Before my eyes a woman came running to a store . . . She had nothing with her: no sack or net bag—so she took off her slip. Her leggings. She stuffed them with buckwheat. Carried it off. All that silently for some reason. Nobody talked.

When I called my mother, there was only mustard left, yellow jars of mustard. “Don’t take anything,” mama begged. Later she told me she was ashamed, because all her life she had taught me differently. Even when we were starving and remembering these days, we still didn’t regret anything. That’s how my mother was.

In town . . . German soldiers calmly strolled in our streets. They filmed everything. Laughed. Before the war we had a favorite game—we made drawings of Germans. We drew them with big teeth. Fangs. And now they’re walking around . . . Young, handsome . . . With handsome grenades tucked into the tops of their sturdy boots. Play harmonicas. Even joke with our pretty girls.

An elderly German was dragging a box. The box was heavy. He beckoned to me and gestured: help me. The box had two handles, we took it by these handles. When we had brought it where we were told to, the German patted me on the shoulder and took a pack of cigarettes from his pocket. Meaning here’s your pay.

I came home. I couldn’t wait, I sat in the kitchen and lit up a cigarette. I didn’t hear the door open and mama come in.

“Smoking, eh?”

“Mm-hmm . . .”

“What are these cigarettes?”

“German.”

“So you smoke, and you smoke the enemy’s cigarettes. That is treason against the Motherland.”

This was my first and last cigarette.

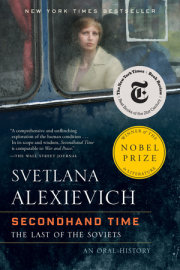

Copyright © 2019 by Svetlana Alexievich. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.