Scales Riptide Latif

The fire music soul cascade was Latif's first serenade, clawing its way out of the family stereo and swirling round his head. He was fourteen years of age, and the dull metal tenor sax on his lap hummed suddenly electric as the redhot blue notes spiraled through it, bouncing like frenzied molecules against the instrument's interior. He had never heard anything like it in his life, this muscular horn spiking holes in the air with every honk and scream, puncturing time as it dove through a cresting tidal wave of drums. The horn dipped and bobbed above the amniotic ocean on winged ankles, shrieked and spiral-dive plummeted into it, vanishing inside the grave of Icarus only to reanimate ichthyoid, a toothy green sea monster undulating over brimstone waves.

Latif rocked and jerked in shifting rhythm, soaking in the serenity and tumult of creation. His music teacher watched and knew he'd made his point and then some. The song ended with bass strings thrumming, drum thunder rumbling in vicious summary and one clear ray of intense light, a horn line so clear it ripped a path from the sun straight through the ocean to the bottom and lit the water from within. The whole sea shimmered tranquil, and suddenly the concordance of these pushing pulling elements was clear: the purposed unity beneath the conflict and the probing and the play.

Mr. Gates relaxed his jaw and waited for Latif to speak. The boy had been his student three years now, and Gates knew without being told that Leda James-Pearson had hired him to give her son weekly lessons out of much more than a simple cultured wish to fill a child's head with music. It was preventive surgery, the desire to graft a saxophone on to an idle hand and innocent mouth before they grew so strong and eloquent that other neighborhood teachers, lounging on trafficked corners and in dusky poolhalls, might find them useful. Latif was bending the corner of that age, strong-wristed and beginning to walk home from school the long way. Obligation to his mother and tacit friendship with his teacher conspired to keep the music lessons coming, but until that afternoon Latif had merely been out to do what everyone he knew was out to do: hustle, push a rap star car through the small radius of Roxbury, Massachusetts, and out into the world beyond, do what had to be done to make a killing.

A killer in the making, his mother thought in darkest moments, watching Latif jaywalk the block to cross the players' paths. Nothing sheathed his interest save a fourteen-year-old's transparent cool, one that fell away at the first acknowledging headnod, phrase, or shoulder-bang embrace. But in the minutes between the delicate dusty touch of stylus to vinyl and the record arm's automatic click, rise, end-of-side glide back into standby--in the song's white spaces, the stolen moments between the saxophone's very notes--Latif's vague aspirations froze and shattered in midair like liquid nitrogen confections.

The truculent truncated boom-kick headbanger boogie of hip hop drums seemed frozen too, all of a moment, like ice chips hacked from glaciers. Hip hop was the indigenous attitude of Latif's ninety decca ecosystem, a malaproper melange of tired braggadocio and quickdraw innovation, pimpology and brothersisterhood. America not as melting pot but mixing board, wedged between two turntables and a microphone, amalgamating tortured newness from the scraps of dying sonic dynasties, postmodern like a motherfucker. The inheritor of Amiri Baraka's poetry-of-new-jazz ploy of cleaving words and letting separate juices flow from each linguistic chunk, hip hop was rap/id, dis/missive, a now/here neighbor/hood, u/n/i/verse the world. Hip hop was rugged drumsounds dredged from the diamond-laden mine of recorded history and reverse-processed into blunt lumps of coal that left your ears sootstreaked with funk.

But the rigidity of sampled sounds was child's play against the mathematics of what Latif had just heard. This drummer's accents shed their skin and slithered; his cymbals hissed with minute tonal variations, and his sticks lunged deadly at the floor toms.

And the horn shining on this record eclipsed every lyrical asswhipping ever spit, burned through the cloudy local soundscape with pure raw open honesty, so emotional yet so precise, so far removed from any kind of pose. After three years laboring in service to an unseen master, working his indifferent lazy-fingered way through the simple melodies his teacher gave him, Latif reached consciousness together with conclusion. He understood upon hearing the record that he must learn to blow this climbing angular tangle of ministry, of history, mystery, and misery in synchronicity--knew it like his mother's hands before he knew what it was or why.

His limbs felt heavier, more profound, as if the knowledge had filled some hollowness within his bones. Latif stared at the bronze of his horn until his eyes softened and unfocused, letting the color melt across his field of vision, then blinked it back to clarity and looked up at Mr. Gates, suddenly the second most important person in Latif's life: the conduit to the tenor player on the record, Albert Van Horn.

They saw each other every day from then on, playing and listening, learning and teaching, talking as musicians. Mr. Gates, Wessel, strained and stuttered to tell everything he could, to hand down ritual and technique, mechanics and folklore, as Latif sat with his head wide open and eyes wired wild with desire. Wessel studied him, amazed, gazing from Latif's ears to his hands and wondering if there was anything inside him, any bone or blood or flesh to slow the flow of knowledge, because it seemed that there was not. Wessel's words and music's sounds entered Latif's ears and tumbled out his horn with freefall speed.

The kid got bad so fast. Things Wess had played at twenty-six, a grown and traveled man, Latif was figuring out by seventeen. Snatches of frenetic luminosity punctuated his solos; he wrapped superstrong infant hands around the language and spoke by squeezing, snapping, and tapping at its joints. He learned to think in diverse signatures and became a black cat flitting underfoot across the regimented path of America's music marathon parade.

By eighteen Latif was ballplayer lanky and clean headed, with intelligent hands and an undated bus ticket to Manhattan. His soft darkbrown gaze rolled across the inert latenight street outside his bedroom window, but his fingers never strayed from the saxophone balanced in his knee-crook. He traced the rimtop with a thumbnail, pressed his heartshaped lips together flat and imagined meeting Van Horn, firm in the resolution that the musician should know nothing of his existence until he was worth Van Horn's knowing. He imagined himself tiptoeing in the great man's shadow, learning secretly by slow degrees, then springing from the darkness fully formed into the light. Night after night Latif in his bedroom listened at Van Horn honk wail scream lament and chastise, stayed up until weak watery sunlight trickled through the window crimebars and striped the walls. He huddled in a tiny energetic ball, or shadowboxed, or paced the room with long unfurling strides as Van Horn played. Sometimes Latif drifted, letting his mind graze and wander fields of fourleaf clover and deadly hemlock, and other times he balled his hands and bowed his head, concentrating on the music note for note.

He left for New York suddenly one morning, two weeks before his nineteenth birthday, redeeming his dogeared ticket and boarding the Bonzai Bus at six a.m. after a final night of study.

Something had surged over his bedroom in the small morning hours, a wellspring of adrenaline Latif had never felt before. It was as if a python cord of energy had looped through him, turned Latif into a needle's eye, connected him to others in a chain, and lifted him until he dangled legs akimbo. Albert Van Horn was in the chain too, and Wessel Gates; Latif felt them both distinctly within the rich black rope of the tradition. Below it was the music, awesome and ordered perfect like life from an airplane window.

Latif touched down still weightless and jumped into the struggle like a soldier from a chopper. He gathered up his saxophone and soloed with the Van Horn solo that was playing; over and under and around it, answering its questions and questioning its answers, covering Van Horn with bursts of protective gunfire when he charged through open battlefields and sprinting in his wake to safety when there was some. When the music ended Latif laid down his horn, feeling spent and ready. He stuffed a duffel bag, tucked a stack of records underneath his arm and lifted the crimebars from his window, vaulted the ledge and clambered down the fire escape, horn in hand. He ran to the bus station in a crazy hopscotch pattern, the sound and rhythm of his footfalls reprising the solo he'd just played. The metronome of his breathing stayed sure and true as Latif ran, sneakers slapping color onto empty streets.

Timekeeping Shedding Dutchman's

New York was two places. There was Dutchman's, five night a week host to the Albert Van Horn Quartet, and there was the hothouse Harlem block on which Latif's boardinghouse crouched, fifteen degrees warmer than life all year round. In a furnished corner room Latif slept, played his horn, and heated breakfast: cans of hash and instant oatmeal on a hotplate he'd set up against the rules. It was either that or clothes-iron grilled cheese, an entree too degenerate to contemplate.

Uptown radiated flavors he knew well. It was depressing and comforting to think that black folks were stuck in the same trifling neighborhoods both here and there, the Apple and the Bean. More shit was open late here, ten 24/7 bodegas for everyone back home, and malt liquor was cheaper in the Bean though advertised as prominently in both cities--as though dudes on their way to work or school or church just up and impulse-copped a forty of Olde English because they saw a poster of a woman with some big titties cradling a bottle in her arms--skidded to a halt in front of the store like Hmm, yes, come to think of it I have been meaning to get inebriated as fuck and thus temporarily forget my plight as a walking crime suspect and police shooting target. I believe I shall get me some drank, forsooth.

Same iambic rhythms to the convo on the streetcorners and same trochaic laughter spearing and reshuffling the rhythms. Same predatory glances shooting from brothers' eyes to sisters' asses and same anger and fear falling from women's downcast eyes onto the pavement. Same churches, same bums. Same deep-frying grease, same chicken and whitefish joints, same snipes for rap albums and gospel shows pasted to the scaffolding of buildings. Same McDonald's and Popeyes crowding out the mom-and-pop joints, same corporate philosophies mandating that eateries in black neighborhoods be short on seating space lest customers get comfortable. Same urban-renewal in the form of trendy clothing chainstores, same keep-the-money-in-the-neighborhood backlash fading before the bottom line.

Only major neighborhood difference Latif noticed off the muscle was the Spanish population, the Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Colombians, and Cubans in the spot. Busybody blockparty mamis held down sidestreet stoops and watched their squealing brightfaced children twist the remote controls of toy monster cars, which zipped circles around the midblock summer domino tables peopled by foursomes of sixty-something caballeros holding ivory bones against their paunches, computations running through their heads. Empty cervezas fr'as jutted from the pavement like stalagmites, and arroz con pollo mingled in the air with yerba. Merengue lit up some apartments, James Brown others. Hip hop drowned everything when Jeeps rolled by, and teenage smoke ciphers chorused their approval when somebody crept through bumping something hot.

Local Spanish businesses were just as raggedy as the black ones, Latif noticed. The boutique some mu-eca had opened up next to the roti spot was as empty as papi's corner deli, tragically understocked with nothing but overripe pl?tanos, stale Dutchies and Private Stock. The TV repair shop was full, but only with electronic junkheaps and the laughter of four mujeres gordas watching telenovelas and playing hearts in the backroom.

The sole independent business on its feet appeared to be Good Buddy Chinese Takeout Kitchen, which in addition to flipping sweet-and-sour chicken and pork fried rice had diversified in order to better serve its customers, embracing a wide multicultural variety of shit you could fry. Folks were particularly open off the mofungo and the Szechuan-style yucca con ajio, dished up hot out the wok with a little soy sauce. Cheap and generous, the spot had garnered a devoted clientele: The young hustlers on the block ate there so much, people joked, that the staff knew everybody's name, address, and diet. If he notice you ain orderin enough iron, money throw some spinach in with your Kung Pao Shrimp no extra charge. Even got free delivery for when you too treed up to walk a half a street up. Styrofoam combination plate containers lined with emptysqueezed packets of duck sauce blew across the sidewalks of the block, slapping Latif's ankles as he made his journey to the downtown train station each evening.

At Dutchman's Latif studied, ate a liquid dinner, worked his hustle. Everyone has one, he'd realized soon after stepping off the bus and into New York's radiant midday. A dream and a hustle. He thought it now, months later, to reassure himself, repeated it to calm the bile simmering in him over what he was and what he feared he wasn't. Latif sat in bed watching calligraphs of smoke rise from the cigarette between his fingertips, left arm locked flat atop the triangle's peak of his knee like the scales of justice. Outside one window: kids playing stickball. Down below the other: an apparent dice game he could only hear, ears tuned to the clicks of red and green cubes tumbling against the buildingside and to the shittalk of the players, which escalated into threats of violence with parabolic predictability. Latif's eyes, agile beneath awnings that hovered a hairsbreadth nearer to the curves of his irises than they used to, were learning to slide across whole spaces rather than dart from A to B.

The kid got bad so fast. Three months off the bus and he was twice the musician he remembered having been, that vague kid who sat up every night inhaling sounds until he hyperventilated himself into a cosmic meditative frenzy, and three times the man. He'd been all nerve endings then, so soaked in the kerosene of his own sweat that a single distant spark could set him thoroughly aflame. Now Latif was firewalking every evening.

The sudden ducats in his wallet burned holes not through his pocket but his patience; the thirst for confrontation had been mounting in Latif for weeks, tickling the back of his parched throat. The fact that he was a jazz world baby, an infant swimming on mere instinct in a reservoir of untapped knowledge, didn't mean shit anymore. He'd slapboxed the thought into submission.

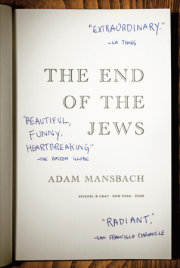

Copyright © 2002 by Adam Mansbach. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.